Steroid-Induced Hyperglycemia Insulin Calculator

How This Tool Works

This calculator helps determine appropriate insulin adjustments based on steroid type, dose, and patient factors. Uses evidence-based guidelines from the article to guide safe insulin dosing during steroid therapy.

Recommended Adjustments

When you’re prescribed steroids like prednisone or dexamethasone for inflammation, asthma, or an autoimmune flare, your blood sugar can spike-even if you’ve never had diabetes before. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s called steroid-induced hyperglycemia, and it affects up to 40% of people on moderate to high-dose steroids. For those already managing diabetes, the rise in blood sugar can be dramatic, dangerous, and hard to predict. The key isn’t just to treat high numbers-it’s to adjust your diabetes meds correctly before things go wrong.

Why Steroids Raise Blood Sugar

Steroids don’t just reduce swelling. They mess with how your body uses insulin. They make your liver pump out more glucose, block insulin from working properly in muscles and fat, and even weaken your pancreas’s ability to release insulin when needed. This triple hit causes blood sugar to climb, usually 4 to 8 hours after taking the steroid. The peak hits around 24 hours and can last for days after the last dose, especially with long-acting steroids like dexamethasone.For someone on 20 mg of prednisone daily, blood sugar can jump from 8 mmol/L (144 mg/dL) to 15 mmol/L (270 mg/dL) or higher. That’s not just inconvenient-it raises your risk of dehydration, infections, and even diabetic ketoacidosis if left unchecked.

Insulin Is Usually the First-Line Fix

Oral diabetes pills like metformin or sulfonylureas often can’t keep up with steroid-driven spikes. That’s why insulin becomes the go-to tool, especially in hospitals and for people with type 1 diabetes. The goal? Match insulin timing and type to the steroid’s action, not just guess.Here’s how it breaks down:

- Prednisone (half-life: 18-36 hours): Starts working fast, peaks in a day, wears off over a few days. Best matched with NPH insulin-it lasts 12-36 hours and lines up well with prednisone’s rhythm. Give it in the morning to cover the steroid’s peak.

- Dexamethasone (half-life: 36-72 hours): Lasts longer, builds up slowly, and sticks around. Needs a long-acting insulin like glargine or detemir, also given in the morning. Evening doses won’t help much because the steroid’s effect doesn’t drop off overnight.

For someone starting steroids, insulin dosing often begins at 0.1 unit per kilogram of body weight. So a 70 kg person starts with about 7 units total-split between basal and bolus. Then, adjust based on blood sugar readings taken before meals and at bedtime. If fasting glucose stays above 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) for two days straight, bump up basal insulin by 10-20%. For spikes above 16.7 mmol/L (300 mg/dL), use a correction dose of 0.08 units per kg.

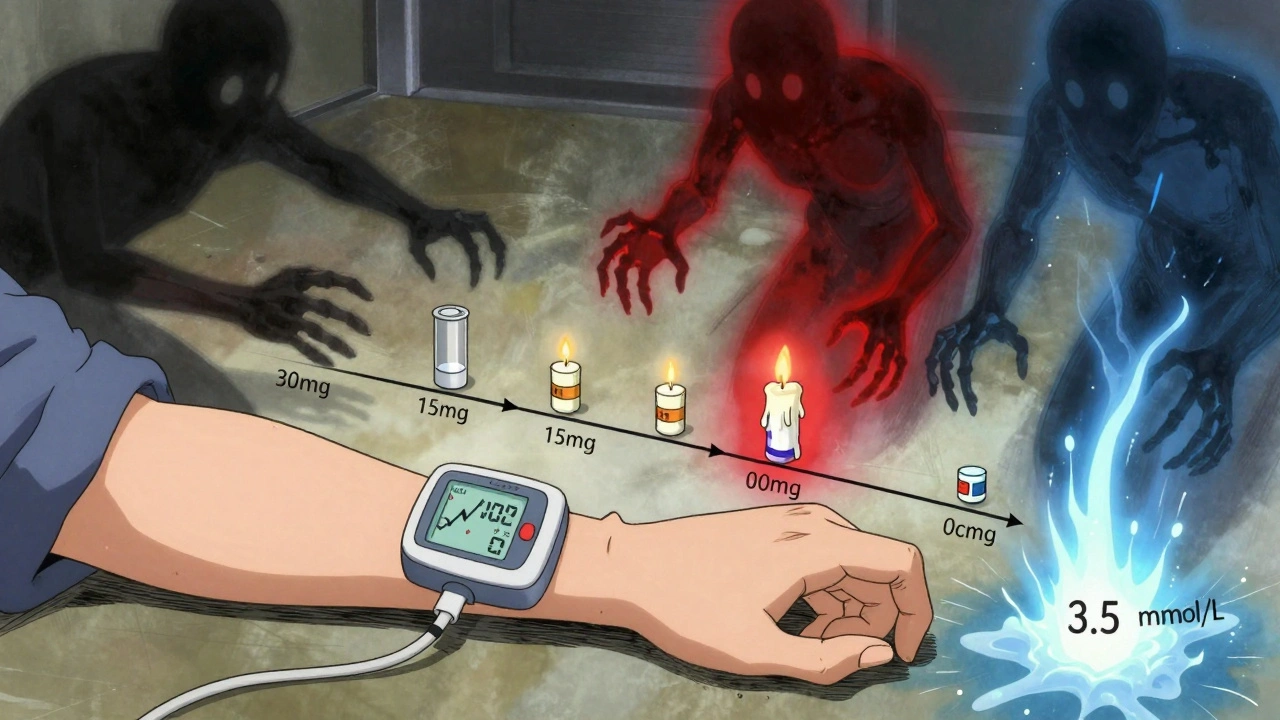

Don’t Forget the Taper-That’s When Things Get Risky

Most people focus on the high blood sugar during the steroid course. But the real danger comes when the steroid is reduced or stopped. That’s when insulin doses haven’t been lowered enough-and blood sugar crashes.Studies show 30-40% of patients on insulin during steroid therapy have at least one episode of dangerous hypoglycemia during tapering. One patient on Reddit shared: “I needed 50% more insulin on 40mg prednisone. When I dropped to 20mg, my endo didn’t cut my insulin fast enough. I had three lows in two days.”

The fix? Reduce insulin as the steroid dose drops. For every 5 mg reduction in prednisone, consider lowering total daily insulin by 10-15%. For dexamethasone, wait until the steroid dose is cut by half before starting insulin reductions. Don’t wait for blood sugar to drop before acting-be proactive. The Joint British Diabetes Societies call this “glucovigilance.”

What About Non-Insulin Medications?

In outpatient settings with mild hyperglycemia (fasting glucose under 11.1 mmol/L), some non-insulin drugs can help. Metformin is often safe and effective. GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide and DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin may also be used. But avoid sulfonylureas like glipizide or glyburide. They force your pancreas to keep releasing insulin-even when the steroid is gone. That’s a recipe for delayed, severe hypoglycemia.A Johns Hopkins study found 27% of patients on sulfonylureas during steroid therapy ended up in the ER for low blood sugar. Only 8% of those on insulin alone had the same issue. If you’re on a sulfonylurea and need steroids, switch to insulin before starting the course.

Monitoring: More Than Just Fingersticks

Checking blood sugar four times a day-before meals and at bedtime-is the bare minimum. But if you’re on high-dose steroids, especially in the hospital, you need more. Every 2-4 hours during dose changes or if glucose is over 16.7 mmol/L. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are becoming standard. They show real-time trends, not just snapshots.Target time in range: 3.9-10.0 mmol/L (70-180 mg/dL) for at least 70% of the day. Time below 3.9 mmol/L should be under 4%. CGMs help catch dips before they become emergencies, especially during steroid tapering.

For insulin pump users, temporary basal rate increases of 25-50% during peak steroid effect can help. But you must reduce those rates quickly as the steroid tapers-otherwise, lows hit hard.

What Hospitals Are Doing Differently

Hospitals are moving away from guesswork. A 2023 survey found 68% now use standardized protocols for steroid-induced hyperglycemia-up from 42% in 2019. These protocols include:- Automatic insulin dosing algorithms based on steroid type, dose, and patient weight

- Pre-filled order sets that suggest insulin amounts based on prednisone or dexamethasone dose

- Electronic alerts when a patient on steroids hasn’t had a glucose check in 6 hours

One study at Massachusetts General Hospital found that 37% of cases of severe hypoglycemia during steroid tapering happened because insulin wasn’t reduced enough. Protocols now include clear instructions: “Reduce basal insulin by 20% when prednisone drops below 15 mg/day.”

Real-Life Scenarios

Case 1: Type 2 Diabetes, New Steroid CourseA 62-year-old on metformin starts 30 mg prednisone daily for a rheumatoid flare. Fasting glucose jumps to 14 mmol/L. The team switches to NPH insulin 10 units in the morning and 4 units of rapid-acting insulin before meals. After 3 days, fasting stays at 12 mmol/L, so basal insulin increases to 12 units. When prednisone drops to 15 mg, basal insulin is cut to 9 units. By day 10 of tapering, insulin is stopped entirely as metformin regains control. Case 2: Type 1 Diabetes, Dexamethasone for Cancer Treatment

A 45-year-old with type 1 diabetes starts 10 mg dexamethasone daily. Basal insulin was 30 units before steroids. They start with 45 units of glargine in the morning and 8 units of insulin aspart with meals. CGM shows time in range drops to 55%. After two days, basal is increased to 50 units. When dexamethasone is cut to 5 mg, basal insulin drops to 35 units. By day 7 after stopping steroids, basal insulin is back to 30 units.

What You Should Do Next

If you’re about to start steroids:- Ask your doctor or diabetes educator to review your current meds-especially if you’re on sulfonylureas.

- Get a CGM if you don’t already have one.

- Know your steroid’s half-life. Prednisone? NPH. Dexamethasone? Glargine.

- Write down your insulin adjustment plan before you leave the clinic.

- Set reminders to check blood sugar more often during the first week.

- When tapering, reduce insulin slowly but steadily. Don’t wait for lows to happen.

Steroid-induced hyperglycemia isn’t a side effect you ignore. It’s a medical event that needs a plan. The best outcomes happen when insulin is matched to the steroid-not the other way around.

Can steroid-induced hyperglycemia turn into type 2 diabetes?

Steroid-induced hyperglycemia doesn’t cause type 2 diabetes, but it can reveal underlying insulin resistance. People who develop high blood sugar on steroids are often already at risk-overweight, sedentary, or with a family history. Once steroids stop, blood sugar usually returns to normal. But if it stays high, you may have prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes. Follow up with an A1C test 3 months after stopping steroids.

How long does steroid-induced high blood sugar last after stopping steroids?

It depends on the steroid. Prednisone’s effect fades in 3-4 days after the last dose. Dexamethasone can linger for up to a week. Blood sugar typically returns to baseline within a week, but insulin doses must be reduced gradually during this time. Don’t stop insulin abruptly-hypoglycemia can happen even days after the last steroid.

Should I avoid steroids if I have diabetes?

No-steroids are often essential for treating serious conditions like severe asthma, autoimmune disease, or cancer-related inflammation. The goal isn’t to avoid them, but to manage the blood sugar spike safely. With proper insulin adjustments and monitoring, most people tolerate steroids without major complications.

Can metformin be used instead of insulin for steroid-induced hyperglycemia?

Metformin can help in mild cases, especially in outpatient settings with fasting glucose under 11.1 mmol/L. But for moderate to severe hyperglycemia, or in hospitalized patients, insulin is faster, more predictable, and safer. Metformin doesn’t work fast enough to control sharp spikes, and it’s not recommended for people with kidney issues or during acute illness.

Why is NPH insulin preferred over long-acting analogues for prednisone?

NPH insulin peaks in 4-12 hours and lasts 12-36 hours, which matches prednisone’s 18-36 hour half-life. Long-acting insulins like glargine have flatter, more constant action-great for dexamethasone, which lasts 36-72 hours. But for prednisone, NPH’s peak aligns better with the steroid’s peak effect, giving tighter control without overdoing it.

Olivia Portier

December 8, 2025 AT 10:20oh my god i just started prednisone last week and my bg spiked to 280!! i thought i was dying lmao. switched to nph like the post said and boom, back to normal. thank u for this, i was about to panic buy a glucose monitor on amazon.

Iris Carmen

December 10, 2025 AT 00:35same. i’m on 10mg dexamethasone for my lupus flare and my endo was like ‘just increase your metformin’ and i was like… bro i’m peeing every 20 mins and my vision is blurry. ngl this post saved my life. cgms are a must.

Ronald Ezamaru

December 10, 2025 AT 22:46For those managing type 1 diabetes on long-acting steroids, the key is anticipating the lag. Dexamethasone’s half-life means insulin needs to be adjusted before the glucose peaks. Many clinicians miss this. Basal rates should be increased preemptively, not reactively. Also, avoid bolusing for high readings during steroid peaks-your insulin sensitivity is suppressed. Focus on basal stability first.

Graham Abbas

December 11, 2025 AT 12:50It’s fascinating how the body’s metabolic response to steroids mirrors evolutionary stress physiology-cortisol surge, gluconeogenesis, insulin resistance. We’re not broken, we’re just reacting to a synthetic mimic of our own fight-or-flight hormones. The real tragedy isn’t the hyperglycemia-it’s that we treat it as a technical glitch instead of a biological signal. Maybe we should ask: why are we giving so many people these drugs in the first place?

Sarah Gray

December 12, 2025 AT 09:10This post is dangerously oversimplified. NPH insulin? In 2025? Glargine and degludec have superior pharmacokinetics. The author clearly hasn’t read the latest ADA guidelines. Also, CGMs are not ‘becoming standard’-they’re the bare minimum for any responsible endocrinology practice. If you’re still finger-sticking four times a day, you’re doing it wrong.

Carina M

December 13, 2025 AT 07:16I find it appalling that medical professionals still treat steroid-induced hyperglycemia as a mere ‘side effect.’ It is a pharmacologically induced metabolic crisis. The fact that sulfonylureas are still prescribed concurrently speaks to a systemic failure in diabetes education. Patients are being set up for failure. This is not medical care-it’s negligence dressed in white coats.

Elliot Barrett

December 14, 2025 AT 18:41Yeah but how many of these people are just lazy and eat carbs? I’ve seen patients on prednisone who eat pizza every day and wonder why their sugar’s through the roof. It’s not the steroid-it’s the donuts.

Brianna Black

December 16, 2025 AT 17:51As a nurse in a busy ICU, I can confirm: steroid-induced hyperglycemia is the silent killer of non-diabetic patients. We’ve had patients code from DKA after being given dexamethasone for sepsis-no prior history, no warning. This protocol should be mandatory in every hospital. I’ve trained 12 residents on this exact algorithm. If your hospital doesn’t have a steroid-glucose protocol, demand one.

Kathy Haverly

December 17, 2025 AT 00:19Wow. So we’re just supposed to trust some random guy on the internet who wrote a 3000-word essay on insulin dosing? What’s next? ‘How to perform your own appendectomy with a butter knife and duct tape’? This isn’t medical advice-it’s a cult. And you’re all drinking the Kool-Aid.

Nikhil Pattni

December 18, 2025 AT 13:51Actually, in India, we have a different approach. We use metformin + gliclazide even with steroids because insulin is expensive and not always available. Also, we use neem leaves and bitter gourd juice as adjuncts. Studies from AIIMS show 62% reduction in glucose spikes with herbal support. So don’t just rely on Western medicine. Ayurveda has been managing this for centuries. Plus, yoga helps. I do 30 minutes of pranayama daily. My sugar is stable. You should try.

Haley P Law

December 20, 2025 AT 03:06OMG I JUST HAD A HYPO AFTER MY STEROID TAPER AND I THOUGHT I WAS GONNA DIE 😭😭😭 THANK YOU FOR THIS POST I WAS SO SCARED I WAS GONNA BE A DIABETIC FOREVER. I’M GETTING A CGM TOMORROW AND I’M TELLING MY ENDO TO READ THIS. I LOVE YOU. 🙏💖

Tejas Bubane

December 20, 2025 AT 20:53Everyone’s acting like this is some groundbreaking discovery. I’ve been on steroids for 12 years. NPH? Glargine? Please. Just use your head. If your sugar’s high, give insulin. If it’s low, eat sugar. Stop overcomplicating it. Also, stop calling it ‘steroid-induced hyperglycemia’-it’s just high blood sugar. We’ve had this problem since the 1950s.

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 21, 2025 AT 04:17It is, regrettably, a matter of considerable concern that such a detailed and clinically nuanced exposition on steroid-induced hyperglycemia should be disseminated in an unregulated online forum, devoid of peer review, editorial oversight, or any semblance of academic rigor. The recommendations, while superficially plausible, lack validation through randomized controlled trials and risk encouraging non-specialist self-adjustment of insulin regimens, thereby precipitating potentially catastrophic outcomes. One would hope that medical institutions would enforce stricter dissemination protocols.

precious amzy

December 22, 2025 AT 16:24One must ask: is this not merely a manifestation of the medical-industrial complex’s addiction to pharmacological intervention? Why not address the root cause-the overprescription of steroids in the first place? Why not promote anti-inflammatory diets, stress reduction, and lifestyle medicine? Instead, we are handed a script for insulin titration as if the body were a malfunctioning engine to be calibrated, rather than a living system to be honored. This is not healing. This is optimization.

William Umstattd

December 24, 2025 AT 15:37Let’s be real-this post is just another way for doctors to make more money. Insulin is expensive. CGMs are expensive. Hospitals profit from this. Meanwhile, people who can’t afford insulin are dying. This isn’t science. It’s capitalism disguised as medicine. And you’re all just helping them sell more pens and pumps.