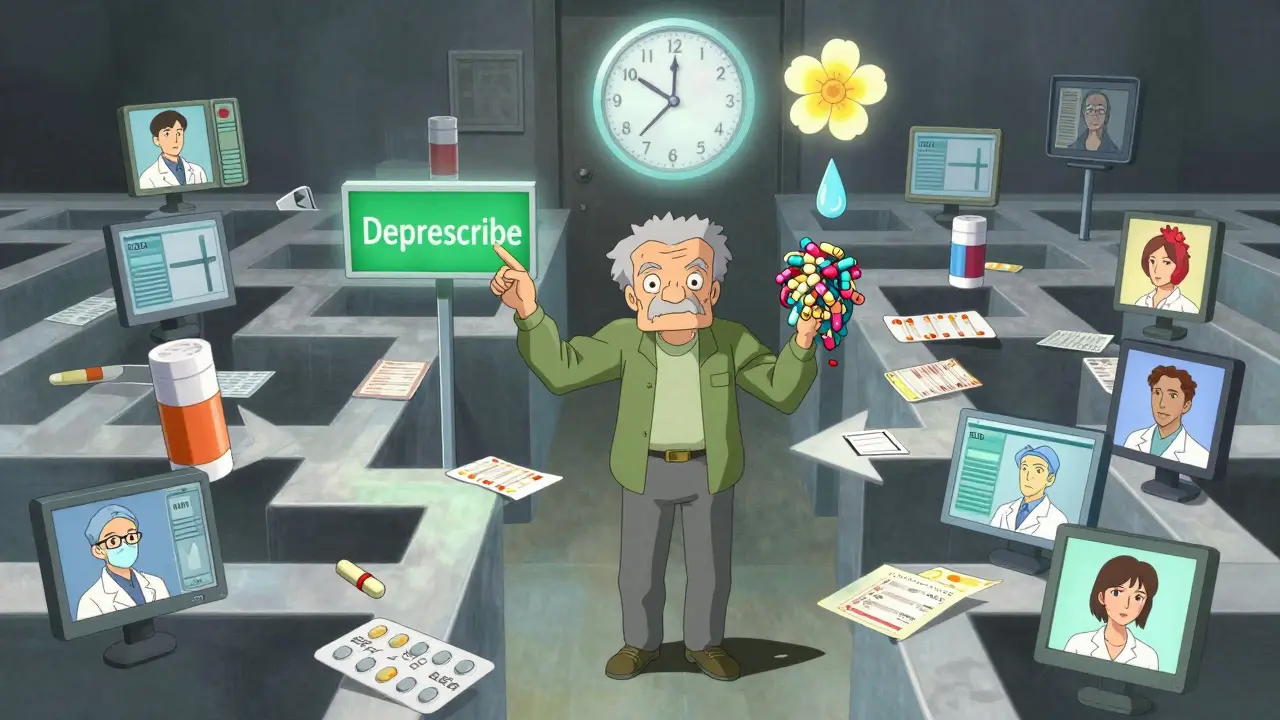

Why So Many Pills? The Reality of Polypharmacy in Older Adults

By age 70, it’s not unusual for someone to be taking five, ten, or even more medications every day. It’s not because they’re overmedicated on purpose - it’s because each doctor is treating a different condition. One prescribes blood pressure medicine, another adds diabetes pills, a third prescribes painkillers, and then there’s the sleep aid, the acid reflux drug, the statin, the osteoporosis tablet, and the occasional aspirin for heart protection. Add in over-the-counter pain relievers, herbal supplements, and PRN meds for anxiety or nausea, and you’ve got a daily pill routine that’s hard to keep track of - let alone take correctly.

This is polypharmacy: the use of five or more medications at once. It’s not a diagnosis. It’s a symptom of how modern medicine works - and how it’s failing older adults. Nearly 4 in 10 people over 65 are taking this many drugs. In nursing homes, it’s closer to 8 in 10. In Australia, it’s 36%. In the U.S., it’s over 65% among those seeing doctors regularly. And the numbers keep climbing. Since 2010, the rate of people taking 10 or more medications has jumped from 10% to nearly 15%. That’s not progress. That’s a warning.

What Happens When You Take Too Many Drugs?

More pills don’t mean better health. They mean more risk. Every extra medication increases the chance of something going wrong. With just two drugs, the risk of a bad interaction is about 6%. With five, it jumps to 50%. With seven or more, it’s almost certain you’ll have at least one problematic interaction.

Older bodies don’t process drugs like younger ones. Kidneys slow down. Liver function declines. Fat replaces muscle, so drugs stick around longer. The brain becomes more sensitive - especially to sedatives, anticholinergics, and painkillers. That’s why a common sleep aid like benzodiazepine can cause falls, confusion, or even delirium in someone over 70. NSAIDs like ibuprofen might ease arthritis pain but can trigger kidney failure or stomach bleeding. Antidepressants that help mood might make someone dizzy or cause urinary retention.

The results are real and dangerous. People on five or more medications are far more likely to fall, break a hip, end up in the hospital, or die prematurely. One study found that for every additional drug added to a regimen, the risk of hospitalization went up by 10%. And it’s not just the drugs themselves - it’s how they interact. A blood thinner plus an NSAID? Higher bleeding risk. A statin plus a certain antibiotic? Muscle damage. A diuretic plus a blood pressure pill? Dangerous drops in sodium or potassium.

And then there’s the hidden problem: prescribing cascades. A patient takes a medication that causes dizziness. Instead of stopping the culprit drug, the doctor prescribes another to treat the dizziness - maybe an anti-nausea pill or a balance aid. Now there are two drugs causing problems, not one. It’s like patching a leak with more tape.

Deprescribing: It’s Not About Stopping Meds - It’s About Stopping Harm

Deprescribing isn’t the opposite of prescribing. It’s not about cutting drugs for the sake of cutting them. It’s about asking: Is this still helping?

Many older adults are on medications they started years ago - for a condition that’s since improved, or for a symptom that’s now managed differently. Maybe the statin was started after a heart attack, but now the person is 85 with no symptoms and frail bones. Maybe the sleeping pill was prescribed after a stressful divorce, and it’s been 12 years. Maybe the antipsychotic was added for agitation in dementia, but the person hasn’t shown signs of aggression in years.

Deprescribing is a planned, step-by-step process. It starts with a full medication review - not just a quick scan of the list, but a deep look at why each drug was started, how long it’s been used, and whether it’s still needed. Tools like the Beers Criteria and STOPP/START guidelines help doctors identify high-risk medications and missed opportunities. For example, Beers says avoid benzodiazepines in older adults. STOPP says don’t give long-term proton pump inhibitors without checking for necessity. START says: if someone has osteoporosis, they should be on a bone-strengthening drug.

But here’s the catch: deprescribing is hard. Doctors don’t have time. Patients are scared. Families insist on keeping everything. One study found that 70% of older adults believe their medications are necessary - even if they can’t explain why. Many think stopping a pill means giving up on treatment. They don’t realize that sometimes, stopping is the most active thing you can do for your health.

What Does Safe Deprescribing Look Like?

Safe deprescribing isn’t a one-time decision. It’s a conversation that happens over weeks or months. Here’s how it works in practice:

- Review the whole list. Include prescriptions, OTCs, vitamins, and herbal supplements. Many people don’t tell their doctor about the turmeric capsules or the melatonin they take every night.

- Identify the red flags. Look for drugs on the Beers list: anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, certain antipsychotics. Check for duplicates - two blood pressure pills from different doctors, for example.

- Ask the patient. What’s working? What’s causing side effects? What’s hard to take? Are they skipping doses because it’s too complicated?

- Start with the lowest-hanging fruit. Don’t tackle everything at once. Stop one drug at a time. Start with the one with the highest risk and lowest benefit - like a sleep aid that hasn’t worked in years, or a cholesterol drug in someone with advanced dementia.

- Go slow. Taper off sedatives, antidepressants, or blood pressure meds gradually. Stopping cold turkey can cause rebound effects: anxiety, insomnia, high blood pressure spikes.

- Monitor closely. Check in after two weeks. Are they sleeping better? Less dizzy? Fewer falls? Any new symptoms? Adjust as needed.

Real success stories exist. In one Australian trial, a pharmacist-led deprescribing program in aged care homes reduced the number of high-risk medications by 30% over six months. Falls dropped by 22%. Emergency visits fell by 18%. Patients reported feeling clearer-headed and more in control.

Why Isn’t Everyone Doing This?

There’s a system problem here. Most doctors are trained to add medications, not remove them. Medical education barely touches deprescribing. Insurance systems pay for prescribing, not for reviewing. A 15-minute appointment isn’t enough to untangle a 10-drug regimen. And when multiple specialists are involved - cardiologist, neurologist, rheumatologist - no one is in charge of the whole picture.

Pharmacists are often the best people to lead this work. They see the full list. They know the interactions. They can spot duplicates and outdated prescriptions. But in most places, they’re still seen as pill dispensers, not medication experts. In Australia, some community pharmacies now offer free medication reviews for seniors - but only if you ask. Most don’t know it’s an option.

Electronic health records can help - they flag potential interactions and high-risk drugs. But they’re full of false alarms. Too many warnings make doctors ignore them. And they don’t ask the real question: Is this still helping this person?

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or someone you care for is taking five or more medications, here’s what to do:

- Make a complete list. Write down every pill, patch, inhaler, and supplement. Include dosages and why you take them.

- Bring it to your next appointment. Don’t assume the doctor knows what’s on it. Bring the actual bottles if you can.

- Ask these three questions: Why am I taking this? Is it still necessary? What happens if I stop it?

- Request a medication review. Ask for a pharmacist-led review - many public health services offer this for free.

- Don’t stop anything on your own. Some drugs need to be tapered. Stopping suddenly can be dangerous.

It’s not about being anti-medication. It’s about being pro-health. Sometimes, the best thing you can do for your body is to take fewer pills - not more.

What’s Next for Older Adults and Medication Safety?

The trend won’t reverse unless the system changes. We need more training for doctors and pharmacists. We need payment models that reward time spent reviewing meds, not just writing prescriptions. We need better tools - AI that flags high-risk polypharmacy patterns, apps that simplify dosing schedules, and shared records that let all providers see the full picture.

But change starts with people asking questions. With families pushing for reviews. With seniors saying, I don’t want to take 12 pills a day just because someone wrote them down years ago.

The goal isn’t to eliminate all medications. It’s to make sure every pill has a purpose - and that no one is left drowning in a sea of pills they no longer need.

What is considered polypharmacy in older adults?

Polypharmacy is generally defined as taking five or more medications at the same time. This includes prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements. Some experts use stricter definitions - like 10 or more drugs - which is called hyper-polypharmacy. The key issue isn’t just the number, but whether each medication is still necessary and safe for the individual.

Are drug interactions really that dangerous for seniors?

Yes. As people age, their bodies process drugs differently. Kidneys and liver don’t clear medications as efficiently, and the brain becomes more sensitive to side effects. The risk of a harmful interaction jumps from 6% with two drugs to 50% with five, and nearly 100% with seven or more. Common dangerous combinations include blood thinners with NSAIDs, statins with certain antibiotics, and sedatives with painkillers - all of which can lead to falls, bleeding, kidney damage, or confusion.

Can stopping medications really improve health in older adults?

Absolutely. Studies show that carefully stopping unnecessary medications can reduce falls by up to 22%, lower hospital admissions, improve mental clarity, and increase energy levels. Many seniors report feeling better after deprescribing - not worse. This is especially true for drugs like benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and long-term proton pump inhibitors, which often cause more harm than benefit in older adults.

Who should lead a medication review for an older adult?

A pharmacist is often the best person to start the review. They’re trained to spot drug interactions, duplicates, and outdated prescriptions. Many community pharmacies offer free medication reviews for seniors. A doctor should be involved to approve changes, especially for high-risk drugs like blood thinners or antidepressants. Ideally, the whole care team - including nurses and specialists - should communicate to avoid conflicting advice.

Is deprescribing safe for people with chronic conditions?

Yes - if done carefully. Deprescribing doesn’t mean stopping all meds for a condition. It means removing ones that are no longer helping or are causing harm. For example, someone with high blood pressure might be on two drugs - one of which is outdated or causing dizziness. Tapering off the riskier one, while keeping the effective one, improves safety without losing control of the condition. The goal is balance: enough medicine to manage illness, but not so much that it causes new problems.

What should I do if my doctor says I need to keep all my medications?

Ask for a second opinion or request a referral to a geriatrician or clinical pharmacist. Many doctors aren’t trained in deprescribing and may default to keeping everything. You can also bring a list of your meds and ask, Which one of these is most likely causing side effects? or Is this still necessary given my current health and goals? If you’re on a Medicare or public health plan, check if you qualify for a free medication review - these services exist in Australia and other countries to help seniors.

Bella Cullen

February 4, 2026 AT 15:44Danielle Vila

February 6, 2026 AT 11:53Dina Santorelli

February 7, 2026 AT 06:27Thorben Westerhuys

February 7, 2026 AT 19:20Laissa Peixoto

February 9, 2026 AT 17:23Lana Younis

February 10, 2026 AT 03:35Samantha Beye

February 11, 2026 AT 05:10Rene Krikhaar

February 11, 2026 AT 08:37Jennifer Aronson

February 11, 2026 AT 10:23lance black

February 12, 2026 AT 22:20Pamela Power

February 13, 2026 AT 13:06Cullen Bausman

February 14, 2026 AT 22:13Cole Streeper

February 16, 2026 AT 05:41Arjun Paul

February 16, 2026 AT 09:12Katharine Meiler

February 16, 2026 AT 15:19