When you pick up a generic prescription at the pharmacy and pay $10, you might assume that money is helping you chip away at your deductible. It’s a natural assumption-after all, you’re spending money on care. But here’s the catch: generic copays usually don’t count toward your deductible. They do count toward your out-of-pocket maximum. And that difference? It can cost you-literally.

What’s the difference between a deductible and an out-of-pocket maximum?

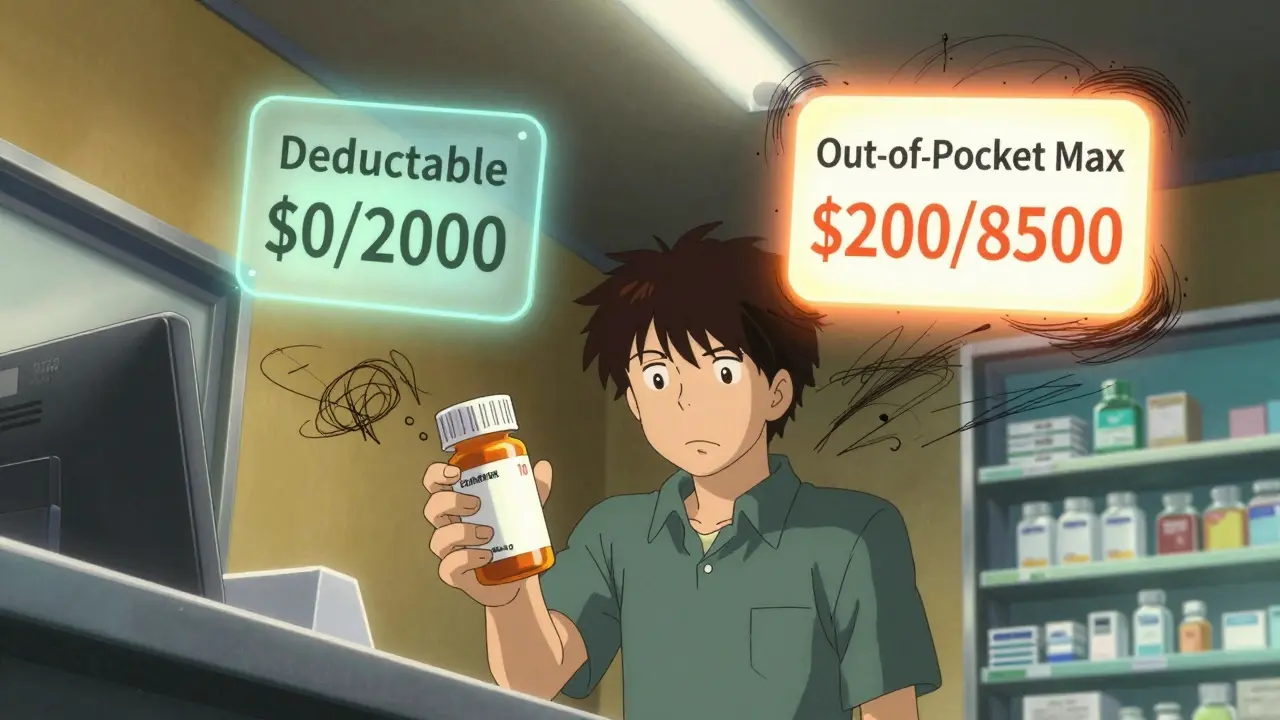

Your deductible is the amount you pay before your insurance starts covering a larger share of your medical bills. If your plan has a $2,000 deductible, you pay the full cost of covered services-like doctor visits or lab tests-until you’ve spent $2,000. After that, you pay coinsurance (say, 20%) until you hit your out-of-pocket maximum.

Your out-of-pocket maximum is the most you’ll pay in a year for covered care. Once you hit that number, your insurance pays 100% of everything else for the rest of the year. For 2026, the federal limit is $10,600 for an individual and $21,200 for a family on Marketplace plans. This cap exists because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which took effect in 2014 to stop people from going bankrupt from medical bills.

Here’s the key point: all your in-network spending-deductibles, coinsurance, and copays-adds up to your out-of-pocket maximum. But only your deductible payments count toward your deductible. Copays? They’re a separate track.

Why generic copays don’t count toward your deductible

Generic drug copays are flat fees-$10, $15, $30-paid each time you fill a prescription. They’re designed to make medications affordable upfront. But they’re not meant to reduce your deductible. Why? Because insurers treat prescriptions differently than doctor visits or hospital stays.

Before the ACA, many plans didn’t even let copays count toward anything. You paid your $15 insulin copay every month, and it didn’t move the needle on your deductible or your out-of-pocket cap. That changed in 2014. Now, those same copays do count toward your out-of-pocket maximum. That’s a huge win if you’re on long-term medication.

But your deductible? Still separate. Let’s say your plan has a $1,500 medical deductible and $10 generic copays. You fill 20 prescriptions in a year: $200 spent. That $200 goes straight to your out-of-pocket maximum. But your deductible? Still at $1,500. You didn’t get closer to it.

This creates a weird gap. You might think, “I’ve paid $2,000 this year-I should be past my deductible.” But you’re not. You’re just closer to your out-of-pocket maximum. And if you need surgery or a hospital stay later in the year, you’ll still owe your full deductible before coinsurance kicks in.

How plan designs make it even more confusing

Not all health plans work the same way. There are three common models:

- Single deductible: One amount covers both medical and prescription costs. If you pay $500 toward prescriptions, it counts toward your $2,000 total deductible. This is simpler, but only used in 27% of employer plans.

- Separate deductibles: You have one deductible for doctor visits and another for prescriptions. Maybe $1,500 for medical, $750 for drugs. You pay each one independently. This is the most common setup-37% of plans use it.

- Copay-only (no prescription deductible): No deductible for prescriptions. You pay your $10 copay right away. But again, that $10 doesn’t touch your medical deductible. This is used in 36% of plans.

If your plan has separate deductibles, your generic copays count toward your prescription deductible-not your medical one. And once you meet your prescription deductible, your copays still count toward your overall out-of-pocket maximum. It’s layered. And most people don’t realize it.

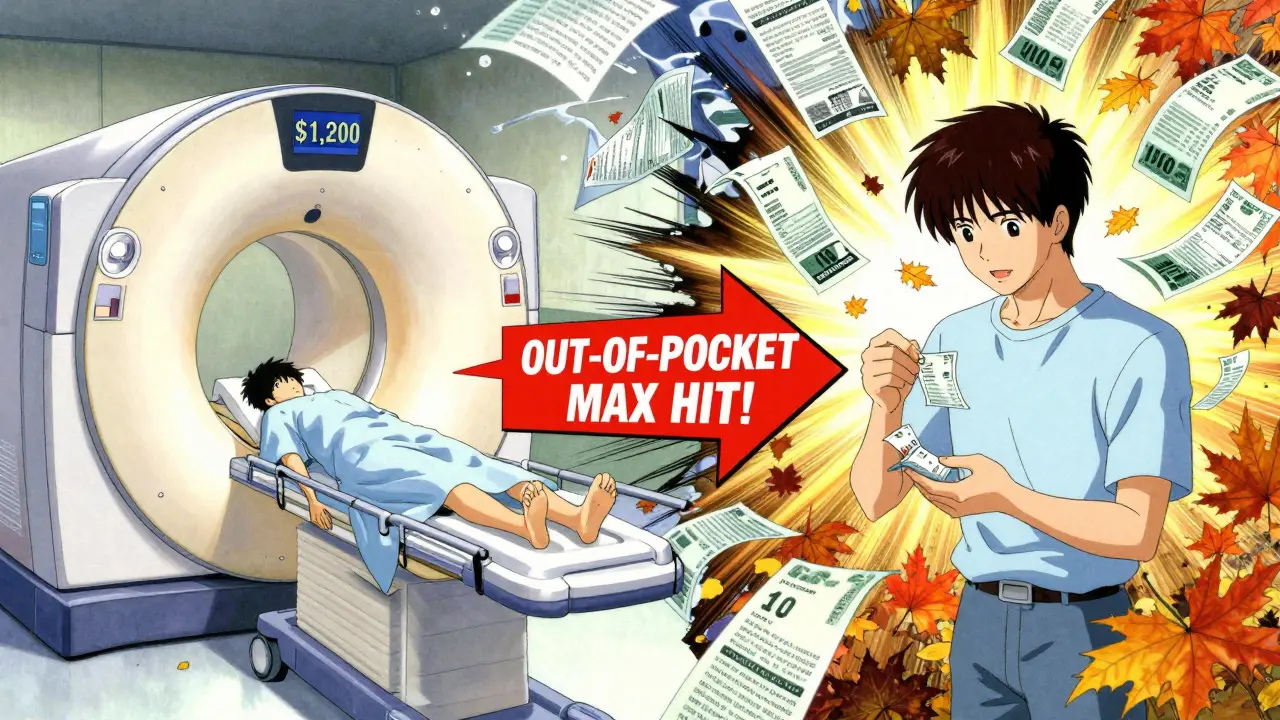

What happens when you hit your out-of-pocket maximum

Let’s say your out-of-pocket maximum is $8,500. You’ve paid $7,800 so far: $3,000 in medical bills, $2,500 in coinsurance, and $2,300 in generic copays for your blood pressure meds, diabetes pills, and asthma inhaler. You’re only $700 away from hitting your cap.

Next month, you need an MRI. It costs $1,200. Because you’re under your out-of-pocket maximum, you pay the full amount. But now you’ve hit $9,000. You’re over the cap. Your insurance pays 100% of everything else for the rest of the year-even if you need more prescriptions, physical therapy, or a specialist visit.

That’s the power of the out-of-pocket maximum. Without it, someone on chronic meds could pay $10,000 a year just to stay alive. Now, they know there’s a ceiling. And those generic copays? They’re the reason they got there.

Why so many people get it wrong

A 2023 survey by America’s Health Insurance Plans found that 68% of people think prescription copays count toward their deductible. Only 22% knew the truth: they count toward the out-of-pocket maximum, not the deductible.

It’s not your fault. Insurance documents are full of jargon. The Summary of Benefits and Coverage (SBC) form is supposed to help, but it’s still dense. One user on HealthCare.gov wrote: “I paid $10 copays for my meds all year. I thought I’d met my $2,000 deductible. I hadn’t. I was shocked.”

Another Reddit user said: “I skipped my ADHD meds for six months because I thought I’d already paid enough. Turns out, I still owed my full deductible.”

Confusion like this leads to $15 billion in lost medication use every year. People avoid prescriptions because they think they’ve “paid enough,” when in reality, they’re still far from their out-of-pocket maximum.

What you should do now

Don’t guess. Check your plan documents.

- Find your Summary of Benefits and Coverage (SBC). It’s required by law and sent to you before open enrollment.

- Look for the section labeled “Cost-Sharing.”

- Check the column that says: “Does this payment count toward your deductible?”

- Find “Generic Prescription Drugs.” If it says “No,” then your copays don’t count toward your deductible.

- Look for “Out-of-Pocket Maximum.” If it says “Includes copays,” then they count toward that.

Also, check if you have a separate prescription deductible. If you do, you’ll pay full price for meds until you hit that number-then you pay copays. Those copays still count toward your overall out-of-pocket maximum.

Pro tip: If you’re on chronic medication, track your spending. Use a spreadsheet or your insurer’s app. Know how much you’ve paid toward your deductible and how much toward your out-of-pocket maximum. You might be closer to free care than you think.

The future is changing

Regulators are noticing the confusion. In 2024, the Department of Health and Human Services mandated clearer language on how copays count-effective for 2025 plans. Some insurers are testing “integrated deductible” models where prescription costs count toward a single deductible. Early results show 28% higher medication adherence.

McKinsey predicts that by 2027, 60% of major insurers will offer at least one plan where generic copays count toward the deductible. Why? Because consumers are demanding it. Simpler is better.

But for now, the system remains split. Your copays are helping you reach your out-of-pocket maximum. They’re just not helping you meet your deductible. And that’s okay-as long as you know it.

Knowing the difference isn’t just about saving money. It’s about staying healthy. If you’re on meds, don’t skip doses because you think you’ve paid enough. You haven’t. But you’re getting closer to paying nothing at all. And that’s the whole point of the out-of-pocket maximum.

Bob Cohen

January 31, 2026 AT 14:11So let me get this straight-I’ve been paying $10 for my blood pressure meds for a year and thought I was halfway to my deductible, but really I was just funding my insurance company’s profit margin? Thanks for the reality check. I feel like I’ve been played by a flowchart.

And don’t even get me started on the SBC forms. They’re written like a legal thriller where the villain is a thesaurus.

At least now I know why my pharmacist looks at me like I’m a confused raccoon when I ask if my copays ‘count’ for anything.

Nidhi Rajpara

January 31, 2026 AT 15:40It is indeed a significant oversight in public health literacy that the distinction between deductible and out-of-pocket maximum is not more widely understood. The structural complexity of American healthcare financing, particularly with respect to cost-sharing mechanisms, is deliberately opaque. This lack of transparency disproportionately affects low-income individuals who rely on generic medications and are unable to navigate bureaucratic documentation. A standardized, plain-language disclosure requirement should be federally mandated, not left to the whims of private insurers.

Furthermore, the 68% statistic cited is not merely a failure of communication-it is a failure of governance.

Lisa Rodriguez

February 2, 2026 AT 14:41OMG I thought I was doing so good paying my $15 copays every month and then I got hit with a $1200 ER bill and realized I still owed my whole deductible 😭

My insurance app doesn’t even separate the two numbers clearly-it just says ‘you’ve paid $2,100 this year’ and leaves you to guess what that means.

Also, why do they call it a ‘copay’ if it doesn’t pay your copayment toward your deductible? That’s just confusing marketing. Like calling a ‘diet soda’ that’s full of sugar.

Someone needs to make a TikTok explaining this. I’d watch it. I’d share it. I’d make my mom watch it.

vivian papadatu

February 4, 2026 AT 11:26I’ve been on insulin for 12 years and I didn’t realize my copays were only counting toward my out-of-pocket max until last year when I had to get an MRI. I was so confused why I still owed $1,500 even though I’d spent over $2,000 on meds.

It’s not just confusing-it’s dangerous. People skip doses because they think they’ve ‘paid enough.’ I’ve seen friends do it. One guy stopped his asthma inhaler because he thought he met his deductible. He ended up in the ER. Again.

Insurance companies know this. They count on it. The system is designed to make you feel like you’re making progress when you’re just running in circles.

But here’s the good part: once you hit that out-of-pocket max? It’s like winning the lottery. Everything else is free. So keep paying. Even if it feels like you’re paying for nothing, you’re building toward freedom.

Track it. Use a spreadsheet. Take screenshots of your statements. You’re not crazy. The system is.

Deep Rank

February 5, 2026 AT 05:57Wow, so you’re telling me people are actually dumb enough to think copays count toward deductibles? Like, how do you even live in this world without reading the fine print? I mean, I get it, insurance jargon is awful, but you can’t just assume things, right? You have to read the document. It’s right there. It’s not hidden. It’s in bold. It’s in a table. It’s not a riddle.

And now you’re blaming the system? The system didn’t make you skip your meds. You did. You didn’t check. You didn’t ask. You just assumed. And now you’re mad because you got what you deserved.

Also, the fact that you think this is some kind of scandal is hilarious. It’s been this way for a decade. If you’re on chronic meds, you’re supposed to know this. It’s not the insurer’s job to baby you. It’s your job to be responsible.

And yes, I’m being harsh. But someone has to say it. The world doesn’t hand out free passes because you didn’t read the manual.

Naomi Walsh

February 5, 2026 AT 11:49How is this even a topic? This is basic healthcare economics 101. The deductible is for utilization of services; copays are for price discrimination and formulary management. The out-of-pocket maximum is a regulatory floor to prevent catastrophic loss. The fact that 68% of Americans misunderstand this speaks less to the system’s complexity and more to the collapse of basic financial literacy.

And frankly, if you can’t read a Summary of Benefits and Coverage form, you shouldn’t be enrolled in a private plan. You should be on Medicaid. Or at least take a 10-minute course on insurance 101. This isn’t rocket science. It’s a table. With headers. And definitions.

Perhaps the real issue is that we’ve normalized ignorance as a cultural virtue. How quaint.

Chris & Kara Cutler

February 6, 2026 AT 10:39THIS. This is the most important post I’ve read all year. 🙌

I just told my sister to stop skipping her diabetes meds because she thought she’d paid enough. She cried. Then she called her doctor. We’re all going to track our spending now. Spreadsheet on the fridge. Color-coded. Done.

Thank you for making this crystal clear. You just saved someone’s health. Maybe mine.

Rachel Liew

February 7, 2026 AT 15:09I just checked my plan and my generic copays don’t count toward my deductible but they do count toward my out-of-pocket max. I had no idea. I’ve been paying $10 for my thyroid med for 2 years and thought I was halfway there. Turns out I’m not even close.

But now I know. And I’m gonna keep filling my prescriptions. Because even if it doesn’t help my deductible, it’s getting me closer to not paying anything at all.

Thanks for explaining this like I’m not a total idiot. I needed this.