Myasthenia gravis isn’t just muscle weakness-it’s weakness that gets worse when you use your muscles and improves when you rest. Imagine lifting your eyelids in the morning, only to have them droop by lunch. Or struggling to swallow your food, then finding it easier after a nap. This isn’t laziness or aging. It’s fatigable weakness, the defining feature of myasthenia gravis (MG), a rare autoimmune disease that attacks the connection between nerves and muscles.

How Myasthenia Gravis Breaks the Nerve-Muscle Connection

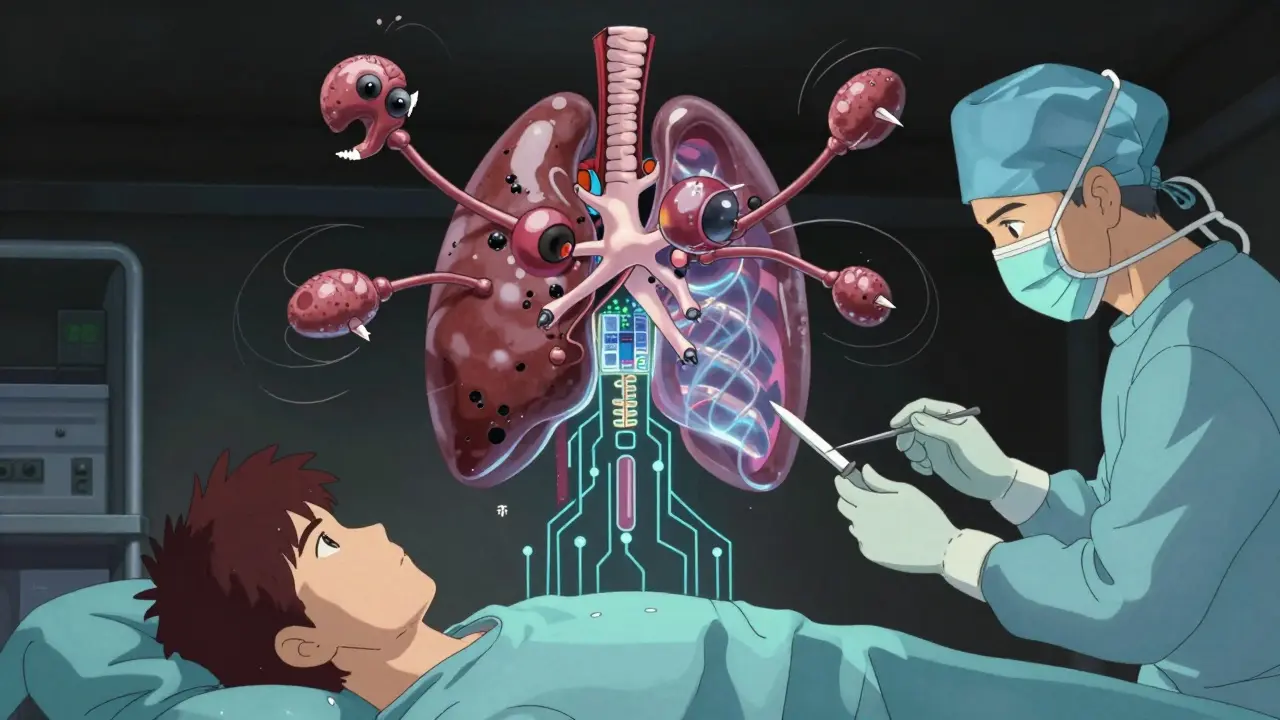

Your muscles move because nerves send signals through a tiny gap called the neuromuscular junction. At that spot, a chemical called acetylcholine is released, binding to receptors on the muscle to trigger contraction. In MG, the body’s own immune system makes antibodies that block or destroy those receptors. Without enough working receptors, the signal fades. The more you use the muscle, the weaker it gets-until it stops responding.

About 80-90% of people with generalized MG have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). Another 5-8% have antibodies targeting muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), which plays a different role in maintaining the junction. The rest are seronegative-no known antibodies found yet, but the disease still behaves the same way. This isn’t random. The immune system has turned against itself, and the damage shows up in the muscles you control voluntarily: eyes, face, throat, arms, and legs.

Who Gets Myasthenia Gravis-and Why It Matters

MG doesn’t pick favorites, but it does have patterns. About two-thirds of cases start before age 50, often in women. These early-onset cases usually come with an enlarged thymus gland, sometimes even a tumor called a thymoma. The other third start after 50, more often in men, and are more likely to have a thymoma. That’s not just a coincidence-it’s a clue. The thymus, a gland behind the breastbone, helps train immune cells. In MG, it seems to be producing the very antibodies that attack the neuromuscular junction.

At first, symptoms are often limited to the eyes: drooping eyelids (ptosis) or double vision (diplopia). That’s called ocular MG. But here’s the catch: 50-80% of those with ocular symptoms will develop generalized weakness within two years. That means trouble speaking, chewing, swallowing, or lifting objects. Fatigue isn’t just tiredness-it’s a sudden, dramatic drop in strength after minimal effort. Walk down the hall? Fine. Walk again five minutes later? Impossible.

The Gold Standard: Symptomatic and Immunosuppressive Treatments

Doctors start with what works fast. Pyridostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, blocks the enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine. More acetylcholine means more chances to bind to the remaining receptors. Doses range from 60 to 240 mg a day, split into 3-4 doses. It helps-sometimes dramatically-but it doesn’t fix the root problem. It just buys time.

For long-term control, you need to calm the immune system. Corticosteroids like prednisone are the first-line immunosuppressant. Starting at 0.5-1.0 mg per kg of body weight, they reduce antibody production. About 70-80% of patients see major improvement or even complete remission. But there’s a cost: weight gain, mood swings, high blood sugar, bone loss. About 70% of people on long-term prednisone (over 10 mg daily) gain noticeable weight. That’s why doctors don’t keep patients on high doses forever.

That’s where steroid-sparing drugs come in. Azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are taken daily to slowly suppress the immune system. Azathioprine takes 6-18 months to work fully but helps 60-70% of patients. Mycophenolate works similarly, with 50-60% success. Both reduce the need for steroids over time. But they come with risks: liver damage with azathioprine (15-20% of users), and higher infection rates overall. People on these drugs are 2-3 times more likely to get serious infections than the general population.

Fast-Acting Rescue: IVIG and Plasma Exchange

What if someone can’t swallow, can’t breathe, or is in the hospital with a myasthenic crisis? Then you need something that works fast-within days, not months. That’s where intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and plasma exchange (PLEX) come in.

IVIG floods the bloodstream with healthy antibodies from donors. These antibodies confuse the immune system, making it pause its attack. Improvement usually shows up in 5-7 days and lasts 3-6 weeks. It’s safe, doesn’t need a central line, and can be done as an outpatient. But it’s expensive and in short supply.

PLEX physically removes the bad antibodies from the blood. It’s faster-often helping in 2-3 days-and more effective in severe cases, especially when bulbar or respiratory muscles are involved. But it requires a large vein access, carries risks like low blood pressure or clotting, and needs multiple sessions over a week or two. Experts agree: both work equally well for crises. But if speed is critical, PLEX wins. If safety matters more, IVIG is the go-to.

Thymectomy: Removing the Source of the Problem

For patients with AChR-positive MG between 18 and 65, removing the thymus isn’t optional-it’s standard. The MGTX trial showed that thymectomy nearly doubles the chance of reaching minimal manifestation status (essentially no symptoms) within three years compared to drugs alone. After five years, 35-45% of early-onset patients achieve full remission without any medication. That’s not a cure, but it’s as close as we get.

Thymectomy is done through minimally invasive surgery. Recovery takes weeks, but the long-term payoff is huge: less drug dependence, fewer flare-ups, and better quality of life. It’s not recommended for MuSK-positive or seronegative patients, because their thymus isn’t the main driver. But for AChR-positive cases, especially under 50, it’s one of the most effective treatments available.

The New Frontier: Targeted Immunotherapies

The biggest shift in MG treatment isn’t just more drugs-it’s smarter drugs. In 2021, the FDA approved efgartigimod, the first drug to target the neonatal Fc receptor (nFcR). This receptor normally recycles IgG antibodies, keeping them alive in the blood. Efgartigimod blocks it, forcing the body to break down all IgG-including the bad ones. In the ADAPT trial, 68% of patients reached minimal manifestation status within weeks. IgG levels dropped 60-75% in just seven days. No IV lines. No hospital stays. Just a weekly infusion or subcutaneous shot.

In 2023, ravulizumab became the first complement inhibitor approved for MG. It blocks part of the immune system that destroys muscle receptors. Both drugs are changing the game: they’re targeted, fast, and don’t suppress the entire immune system like steroids do. But they’re expensive, and long-term safety data beyond two years is still limited.

For MuSK-positive MG, rituximab-originally used for lymphoma-has shown remarkable results. Up to 89% of these patients improve significantly, compared to only 40-50% in AChR-positive cases. That’s why doctors now test for antibody type before choosing treatment. One size doesn’t fit all.

The Dark Side: When Treatments Backfire

Not all new therapies are safe for everyone. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), used to treat cancers like melanoma and lung cancer, can trigger severe MG-sometimes for the first time. In a 2022 case series, 60% of patients who developed ICI-induced MG also had heart inflammation (myocarditis). Eighty-three percent needed ICU care. It’s rare, but deadly. Oncologists now screen for MG symptoms before giving ICIs. If MG appears, treatment stops immediately.

Even standard drugs have hidden dangers. Azathioprine can cause liver damage. Steroids can lead to diabetes or osteoporosis. Long-term immunosuppression increases cancer risk. That’s why doctors aim for the lowest effective dose and try to taper off after two years of stable remission. But if you taper too fast, 40-50% of patients relapse.

What Success Looks Like

Success in MG isn’t about curing the disease-it’s about controlling it. The goal is minimal manifestation status: no symptoms, no daily meds, no hospital visits. About 10-20% of patients go into spontaneous remission. Most need ongoing treatment. But with the right mix of drugs, surgery, and newer biologics, 70-80% can live with near-normal function.

Tracking progress matters. Doctors use the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis Score (QMGS). A score above 11 means moderate to severe disease-time to start immunosuppression. Below 5? You’re doing well. Below 1? You’re in remission.

The future? Researchers are testing drugs that target specific B-cells, block cytokines, or silence the immune response at the genetic level. Fifteen clinical trials are active as of late 2023. The top priority? Achieving disease control without lifelong immunosuppression. That’s the real win.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is myasthenia gravis curable?

There’s no cure yet, but many people achieve long-term remission. About 35-45% of early-onset AChR-positive patients who have a thymectomy go into complete remission without drugs after five years. Others control symptoms well with medication. The goal isn’t always a cure-it’s living without symptoms.

Can stress make myasthenia gravis worse?

Yes. Stress, illness, heat, and overexertion can trigger flare-ups. The immune system reacts to stress by becoming more active, which can ramp up antibody production. Managing stress through rest, sleep, and avoiding extreme temperatures helps keep symptoms stable.

Why do symptoms get worse during the day?

Because the neuromuscular junction runs out of usable acetylcholine receptors as you use your muscles. The more you move, the more receptors get blocked or destroyed by antibodies. Rest lets the remaining receptors recover enough to work again. That’s why fatigue is the hallmark-it’s not tiredness, it’s signal failure.

Can I still exercise with myasthenia gravis?

Yes-but carefully. Light, regular exercise like walking or swimming helps maintain muscle strength and prevents deconditioning. Avoid intense workouts or pushing to exhaustion. Stop if you feel weakness increasing. Many patients find that short, frequent sessions are better than long ones.

Do I need to avoid certain medications?

Absolutely. Some antibiotics (like macrolides and fluoroquinolones), beta-blockers, magnesium, and lithium can worsen MG. Even over-the-counter drugs like antihistamines and some sleep aids can cause problems. Always check with your neurologist before starting any new medication, including supplements.

What’s the difference between IVIG and plasma exchange?

IVIG adds healthy antibodies to confuse the immune system and works in 5-7 days. Plasma exchange removes the bad antibodies directly and works faster-2-3 days-but requires a central line and carries more risks. Both are used for emergencies. IVIG is safer for outpatients; PLEX is preferred for severe breathing or swallowing problems.

Can myasthenia gravis affect my heart?

Usually not directly. MG affects skeletal muscles, not the heart. But if you develop immune-related MG from cancer immunotherapy, up to 60% of cases involve myocarditis-an inflammation of the heart muscle. That’s rare with typical MG but serious when it happens. Always report chest pain, palpitations, or shortness of breath.

Diksha Srivastava

January 31, 2026 AT 00:29This post gave me chills. I’ve seen my mom live with MG for 12 years, and this is the first time someone explained fatigable weakness like it’s actually happening to a person, not just a textbook definition. She doesn’t ‘just get tired’-she loses the ability to lift her coffee cup after two sips. That’s not laziness. That’s her body betraying her. Thank you for writing this.

Sidhanth SY

January 31, 2026 AT 17:10Man, I didn’t know thymectomy could do that much. I thought it was just some old-school surgery. The fact that 45% of early-onset patients go into full remission after five years? That’s wild. I’ve got a cousin who’s AChR-positive and just turned 30-gonna send this to his neurologist. Maybe it’s time to push for it.

Adarsh Uttral

February 2, 2026 AT 13:37so i read this whole thing and im just like… why is this not common knowledge? like people think its just ‘being tired’ or ‘aging’ and its like… no its your immune system actively sabotaging your muscles. its wild. also why is ivig so expensive???

Niamh Trihy

February 2, 2026 AT 23:20As a neurology nurse in Dublin, I’ve seen too many patients misdiagnosed for years because doctors dismiss ptosis as ‘just tired eyes.’ This is textbook-level accurate. The distinction between MuSK and AChR is critical-so many clinicians still treat them the same. Thank you for highlighting the antibody-specific treatment pathways.

KATHRYN JOHNSON

February 4, 2026 AT 19:14Why are we spending billions on these new biologics when we could just fix the thymus early? This is a first-world problem. In India, they don’t have access to efgartigimod, but they still manage with pyridostigmine and steroids. Why aren’t we pushing for global access instead of luxury drugs?

Sazzy De

February 6, 2026 AT 11:26My brother was diagnosed last year. He started on prednisone and gained 40 pounds in 4 months. We didn’t know it was normal until we read this. He’s on mycophenolate now and feels better. Still tired all the time but at least he can walk to the mailbox without stopping. This post is the only thing that made sense.

Amy Insalaco

February 7, 2026 AT 12:59While the pharmacokinetics of efgartigimod’s FcRn antagonism are indeed elegant, one must contextualize its clinical utility within the broader ontological framework of autoimmune dysregulation. The reduction of IgG titers, while statistically significant, does not necessarily correlate with functional improvement in QMGS scores across heterogeneous phenotypes. Moreover, the cost-effectiveness analysis remains underpowered in real-world cohorts, particularly when considering the temporal decay of therapeutic effect post-infusion. One wonders whether we are optimizing biomarkers rather than lived experience.

Natasha Plebani

February 8, 2026 AT 23:06It’s fascinating how MG forces us to confront the illusion of bodily autonomy. We assume our muscles obey us, but in reality, they’re hostages to an invisible war inside our immune system. The neuromuscular junction isn’t just a synapse-it’s a battlefield. And the fact that rest restores function? That’s not physiology. That’s mercy. We don’t cure MG-we negotiate with it. And maybe that’s the real lesson: healing isn’t always about erasing the enemy. Sometimes it’s about learning to live with the ceasefire.

Kimberly Reker

February 9, 2026 AT 00:20For anyone new to this-don’t feel guilty for needing rest. It’s not laziness, it’s survival. I used to feel ashamed when I had to cancel plans because my arms gave out. Now I say: ‘My muscles are on strike today.’ And I mean it. You’re not broken-you’re fighting a war no one sees. Keep going. You’re doing better than you think.

calanha nevin

February 9, 2026 AT 07:07Thank you for the comprehensive overview. The distinction between IVIG and PLEX in bulbar crisis is clinically vital. I would add that early thymectomy in AChR-positive patients under 50 should be considered standard of care, not an option. The MGTX trial data is robust and underutilized. Additionally, patients should be monitored for thymoma recurrence even after complete resection. Long-term follow-up remains essential.

Lisa McCluskey

February 11, 2026 AT 04:09I’m a caregiver for someone with MuSK-positive MG. Rituximab changed everything. We thought we’d be on steroids forever. After two rounds, she went from needing help to stand to hiking again. No one told us it worked better for MuSK than AChR. This post saved us months of guesswork. Thank you.

Russ Kelemen

February 11, 2026 AT 07:27One thing no one talks about: the emotional toll of being told you’re ‘just tired’ for years. I was diagnosed at 28 after six doctors said it was anxiety. When I finally got the right test, I cried for an hour. This isn’t just a medical condition-it’s a story of being unseen. If you’re reading this and you’ve been dismissed… you’re not crazy. You’re not lazy. You’re fighting something real. And you’re not alone.