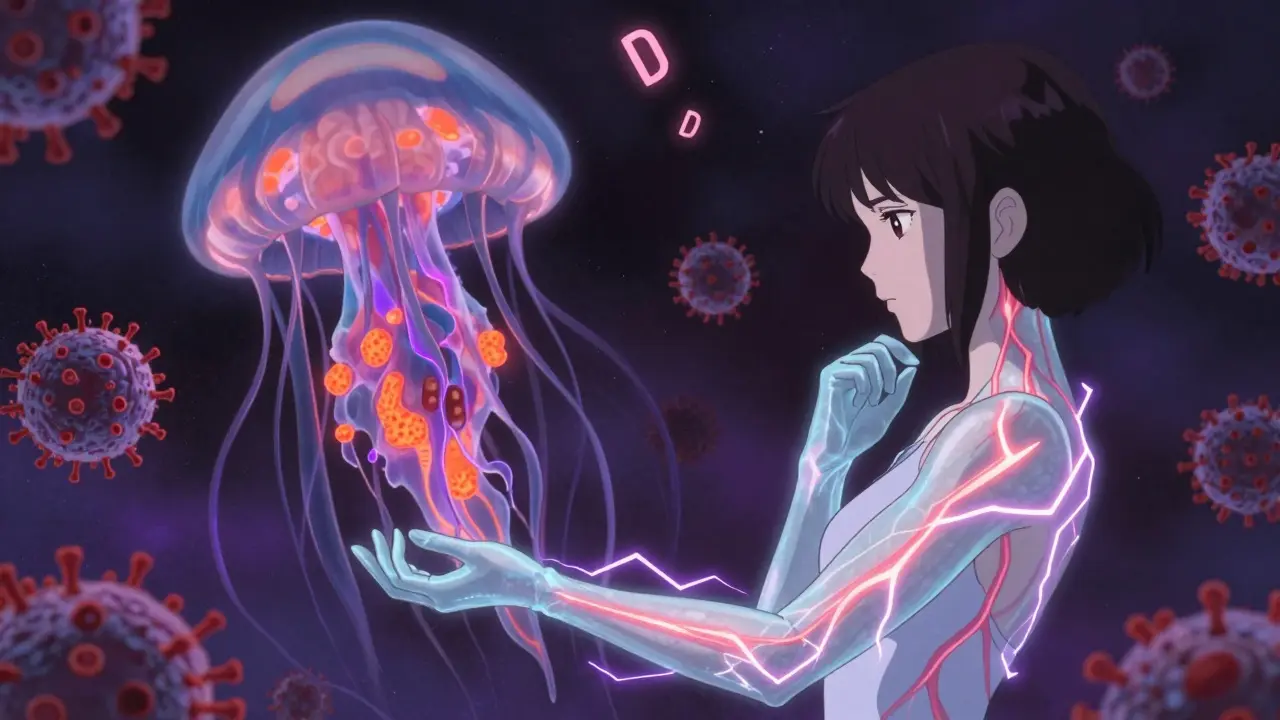

Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological condition-it’s an immune system attack on the body’s own nervous system. Every day, in brains and spines around the world, immune cells that were meant to protect us turn against the very tissue they’re supposed to guard. They break through a natural barrier, invade the central nervous system, and start stripping away the protective coating around nerve fibers. That coating? Myelin. And when it’s gone, signals slow down, stutter, or stop entirely. What follows isn’t just a medical diagnosis-it’s a cascade of real, daily struggles: blurred vision, numbness, fatigue so deep it feels like gravity doubled, and the terrifying uncertainty of when the next flare-up will hit.

What Happens Inside the Nervous System During an MS Attack?

Think of your nerves like electrical wires. Myelin is the rubber insulation wrapped around them. It keeps the signal strong and fast. In multiple sclerosis, the immune system mistakes myelin for a foreign invader-like a virus or bacteria-and launches an assault. The main culprits? CD4+ T cells, B cells, and microglia. These aren’t rogue agents; they’re normal immune cells gone rogue because of a mix of genetics and environment.

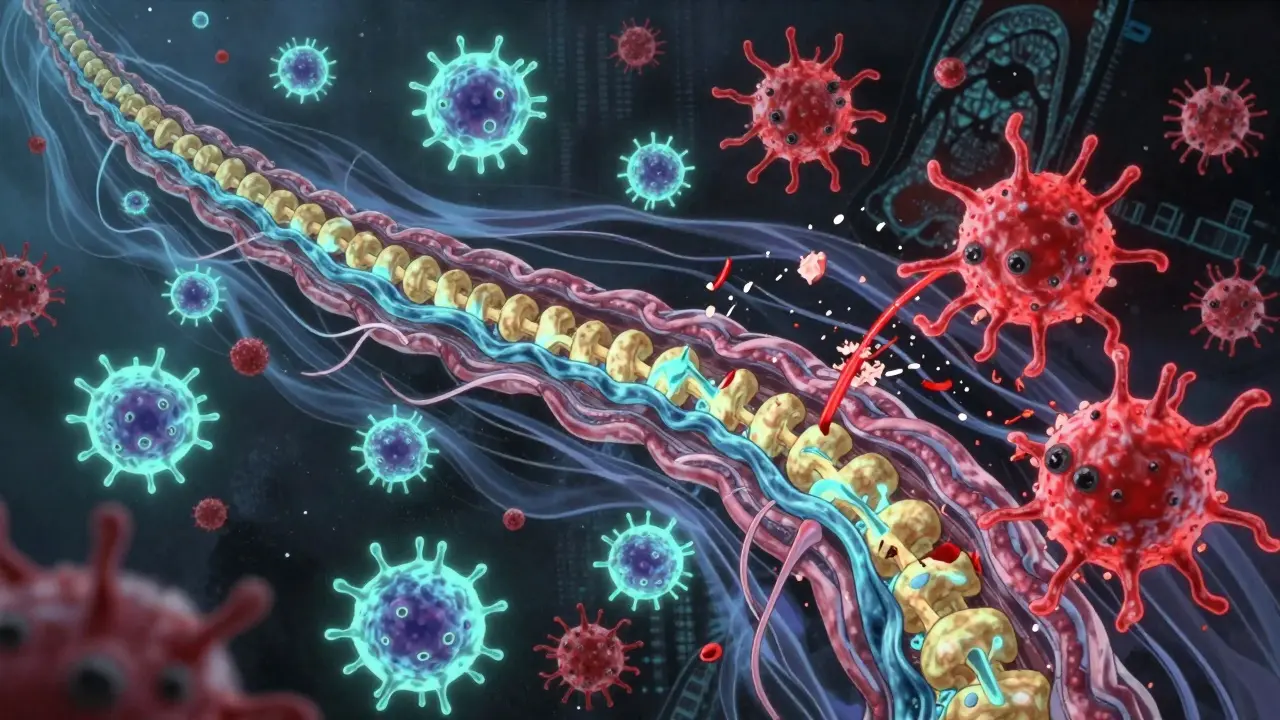

The attack starts when immune cells cross the blood-brain barrier, a protective wall that usually keeps harmful substances out of the brain and spinal cord. Once inside, they find myelin and begin to destroy it. This process is called demyelination. Each damaged area becomes a scar-or a lesion-visible on MRI scans. These lesions aren’t just patches of dead tissue; they’re active war zones. Macrophages swarm in, gobbling up the shredded myelin. Microglia, the brain’s own immune guards, go into overdrive, releasing chemicals that make the inflammation worse. In some cases, the nerve fibers underneath-the axons-start to fray and die. That’s when damage becomes permanent.

There are four known patterns of this damage, based on what immune cells are present and how the myelin breaks down. Pattern I is mostly T cells and macrophages. Pattern II adds antibodies to the mix. Pattern III shows a strange, selective loss of a specific myelin protein. Pattern IV is the most devastating: oligodendrocytes-the cells that make myelin-die off without any sign of repair. The body tries to fix this. Sometimes, it even rebuilds a little myelin. But in most people with MS, the inflammation is too fierce, and the repair system gets overwhelmed.

Why Does This Happen? The Triggers Behind the Attack

No one person gets MS for the same reason. It’s not inherited like eye color. It’s not caught like the flu. It’s a perfect storm of genes and environment. If you have a close relative with MS, your risk goes up-but only to about 2-5%. That means genes alone aren’t enough.

The biggest environmental trigger? Epstein-Barr virus. Nearly everyone with MS has been infected with EBV, the virus that causes mononucleosis. Studies show people who’ve had EBV are 32 times more likely to develop MS than those who haven’t. It’s not that EBV causes MS directly. It’s more like the virus rewires the immune system in a way that makes it more likely to turn on myelin.

Another big player is vitamin D. People living farther from the equator-like in Canada, Scandinavia, or southern Australia-have higher MS rates. Sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, and low levels are linked to a 60% higher risk of developing MS. Smoking is another major risk. Smokers with MS progress faster, and their lesions are more aggressive. Even secondhand smoke increases risk.

Women are two to three times more likely to get MS than men. Why? Hormones may play a role. Estrogen seems to have some protective effect, which might explain why some women see fewer relapses during pregnancy. But the exact reasons for this gender gap are still being studied.

What Do the Symptoms Really Feel Like?

MS symptoms aren’t just listed in medical textbooks-they’re lived experiences. Eighty percent of people with MS report crushing fatigue. Not tired from a long day. Tired like your body’s been drained of all energy, even after sleeping 10 hours. It’s not mental. It’s neurological. Your brain is working overtime just to send basic signals.

One in three people experience vision problems early on. Optic neuritis-when the optic nerve gets inflamed-can cause sudden blurriness, pain with eye movement, or even temporary blindness in one eye. For many, it’s the first sign something’s wrong. Others feel numbness or tingling in their arms, legs, or face. It’s not like pins and needles from a foot falling asleep. It’s a constant, odd sensation, like wearing invisible gloves or socks that don’t come off.

Walking becomes harder. Not because muscles are weak, but because the signals from the brain to the legs are delayed or lost. Some people describe it as dragging their feet. Others lose balance easily. Then there’s Lhermitte’s sign: a sharp electric shock that runs down the spine when you bend your neck. It’s startling, uncomfortable, and unmistakable to those who’ve felt it.

These symptoms come and go. In relapsing-remitting MS-the most common form-people have flare-ups (relapses) that last days or weeks, then settle down (remission). But even during remission, damage is quietly building. Over time, the relapses become less frequent, but the disability grows. That’s when many shift into secondary progressive MS. A smaller group-about 15%-have primary progressive MS from the start. Their decline is steady, with no clear relapses, just a slow worsening.

How Do Treatments Stop the Attack?

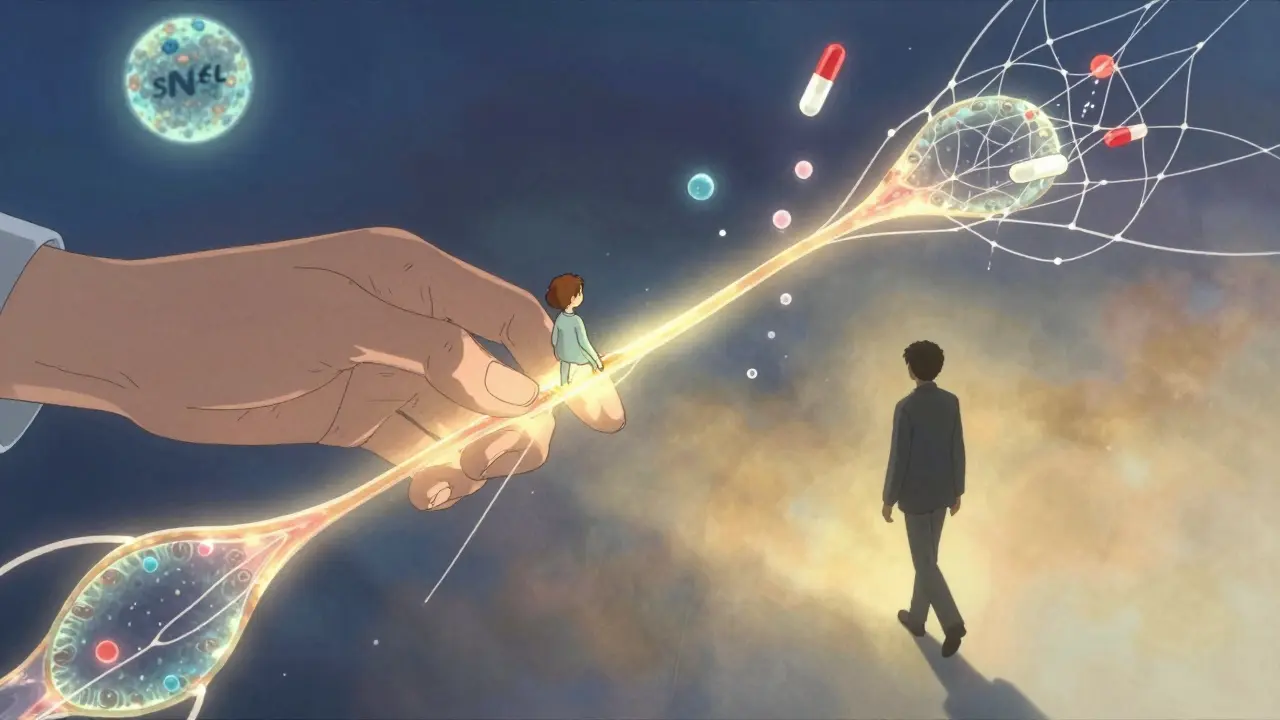

Treatments for MS don’t cure it. But they do stop the immune system from attacking. These are called disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). They work in different ways.

Some, like ocrelizumab, target B cells. These cells don’t just make antibodies-they also pump out inflammatory chemicals. Ocrelizumab clears them out, reducing relapses by 46% and slowing disability progression by 24% in progressive forms. Others, like natalizumab, block immune cells from crossing the blood-brain barrier. It’s powerful-cutting relapses by 68%-but risky. A rare but serious brain infection called PML can happen, especially after two years of use.

Newer drugs are even more targeted. Some interrupt signals between immune cells. Others calm down microglia. The goal isn’t just to suppress the immune system. It’s to stop the attack without leaving the body defenseless against real infections.

One of the most exciting areas is repair, not just suppression. Researchers are testing drugs like clemastine fumarate, which helped patients in early trials show signs of myelin regrowth. In one study, visual signal speed improved by 35%. That’s not just a lab result-it means better vision, better function, better life.

What’s on the Horizon?

Science is moving fast. One breakthrough? Finding biomarkers that predict how the disease will act in each person. Blood tests for neurofilament light chain (sNfL) can now show if inflammation is active-even before symptoms appear. Levels above 15 pg/mL mean the immune system is still attacking. That lets doctors adjust treatment before damage piles up.

Another discovery: neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs. These are sticky webs of DNA and proteins released by immune cells that help trap germs. In MS, they tear apart the blood-brain barrier and wake up microglia. Blocking NETs could be a new way to stop attacks before they start.

Dendritic cells, usually the immune system’s messengers, are now seen as key players in MS. In people with MS, these cells hang out near brain blood vessels, handing myelin pieces to T cells like wanted posters. Targeting them could stop the attack at its source.

The International Progressive MS Alliance has poured $65 million into research since 2014. Projects are running in 14 countries. The goal? To turn progressive MS from a sentence into a manageable condition.

Living With the Aftermath

MS doesn’t end when the flare-up fades. The damage stays. That’s why early treatment matters so much. Without DMTs, half of people with relapsing MS need help walking within 15 to 20 years. With modern therapies, that number drops to about 30%. That’s not just a statistic-it’s the difference between independence and dependence.

People with MS are learning to adapt. Physical therapy helps with balance. Cooling vests reduce fatigue triggered by heat. Apps track symptoms and flare-ups. Support groups on Reddit or local MS societies offer more than advice-they offer proof you’re not alone.

There’s no magic cure. But there’s hope. The immune system doesn’t have to be the enemy forever. Science is learning how to redirect it, calm it, and even repair what it broke. For the first time, we’re not just slowing the disease-we’re starting to reverse it.

Stewart Smith

January 1, 2026 AT 03:55Man, I read this while sipping coffee at 3 a.m. and just felt my whole body get heavier. Not because I have MS, but because I now get how brutal it is to live inside a body that betrays you. I’ve seen my cousin go from hiking mountains to needing a cane in five years. No one talks about how the fatigue isn’t tired-it’s like your bones are full of wet sand.

Aaron Bales

January 2, 2026 AT 22:48DMTs work best when started early. sNfL biomarkers are now standard in neuro clinics for monitoring subclinical activity. Don’t wait for symptoms to worsen-action now prevents irreversible axonal loss.

Joy Nickles

January 4, 2026 AT 18:00Wait, so you’re saying EBV causes MS??? Like… the virus that gives you mono?? I had that in college and I’m fine?? I mean, what about all the other people who had it?? And why do they say vitamin D helps?? I live in Arizona and I’m still fatigued?? Also, I think the author is just trying to sell supplements…

anggit marga

January 5, 2026 AT 01:01Why do Americans always make everything about science and drugs? In Nigeria we use herbs and prayer. My uncle had MS and he walked again after drinking bitter leaf tea and fasting for 40 days. You people are too dependent on pills. Your bodies are weak because you eat too much sugar and sit on chairs all day. We don’t need your labs and your MRI machines. We have faith.

Darren Pearson

January 6, 2026 AT 02:38While the article presents a commendable synthesis of current immunological understanding, one cannot help but note the conspicuous absence of any meaningful engagement with the epistemological frameworks underpinning neuroimmunology. The reductionist model of demyelination as an ‘attack’ presupposes an anthropomorphic agency in immune cells-an ontological category error that risks reifying biological processes as intentional acts. Furthermore, the uncritical adoption of the ‘lesion = damage’ paradigm fails to account for the dynamic plasticity of neural networks, which may compensate via synaptic reorganization. One wonders whether the therapeutic focus on immunosuppression is not merely a reflection of pharmaceutical incentives rather than neurobiological necessity.

Martin Viau

January 7, 2026 AT 13:28NETs? Really? Another overhyped neutrophil thing? We’ve had 12 papers on NETs in MS since 2020. Half of them were from labs that couldn’t replicate their own controls. And clemastine? That’s a 60-year-old antihistamine repurposed because Big Pharma ran out of new targets. Let’s not confuse pilot studies with progress. We’re still 15 years from a cure. And the ‘repair’ hype? It’s just the same old hope porn with new jargon.

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 8, 2026 AT 05:56It’s so sad. People are dying because they don’t pray enough. This whole thing is a punishment. Look at how many people live in sin-eating junk, not going to church, watching TV all day. God doesn’t make mistakes. If you have MS, you broke a rule. You didn’t honor your body. You didn’t honor God. I’m not judging, but… you know? The Bible says, ‘Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.’

John Chapman

January 9, 2026 AT 09:05THIS IS WHY WE NEED MORE FUNDING 😭 I just lost my sister to PPMS and I swear if one more person says ‘it’s just fatigue’ I’m gonna scream. But look-there’s HOPE. Clemastine? NETs? Biomarkers? WE’RE GETTING THERE. I’m donating to the MS Society this month. You should too. 💪❤️ #MSWarrior #CureInOurLifetime

Marilyn Ferrera

January 11, 2026 AT 07:55It’s not about stopping the immune system. It’s about teaching it to listen again. The body knows how to heal. We just need to remove the noise-the inflammation, the stress, the toxins. My patient reduced her relapses by 80% with diet, meditation, and sunlight. Not drugs. Not surgery. Just presence. Science is catching up to what intuition has always known.

Jenny Salmingo

January 12, 2026 AT 21:52I’m from the Philippines. We don’t have fancy MRIs or drugs like ocrelizumab. But we have family. We cook for each other. We sit with people who can’t walk. We sing to them. We don’t call it ‘progressive’-we call it ‘still here.’ Maybe the real cure isn’t in the lab. Maybe it’s in the hands that hold yours when you cry.