When someone survives a medication overdose, it doesn’t mean they’re out of danger. Many people assume that if they wake up in the hospital and are discharged, the worst is over. But the truth is, the damage from an overdose can keep growing long after the emergency is over. The body doesn’t just bounce back. Organs, nerves, and especially the brain can suffer lasting harm - sometimes silently, sometimes slowly, but always permanently.

Brain Damage Is Common - And Often Permanent

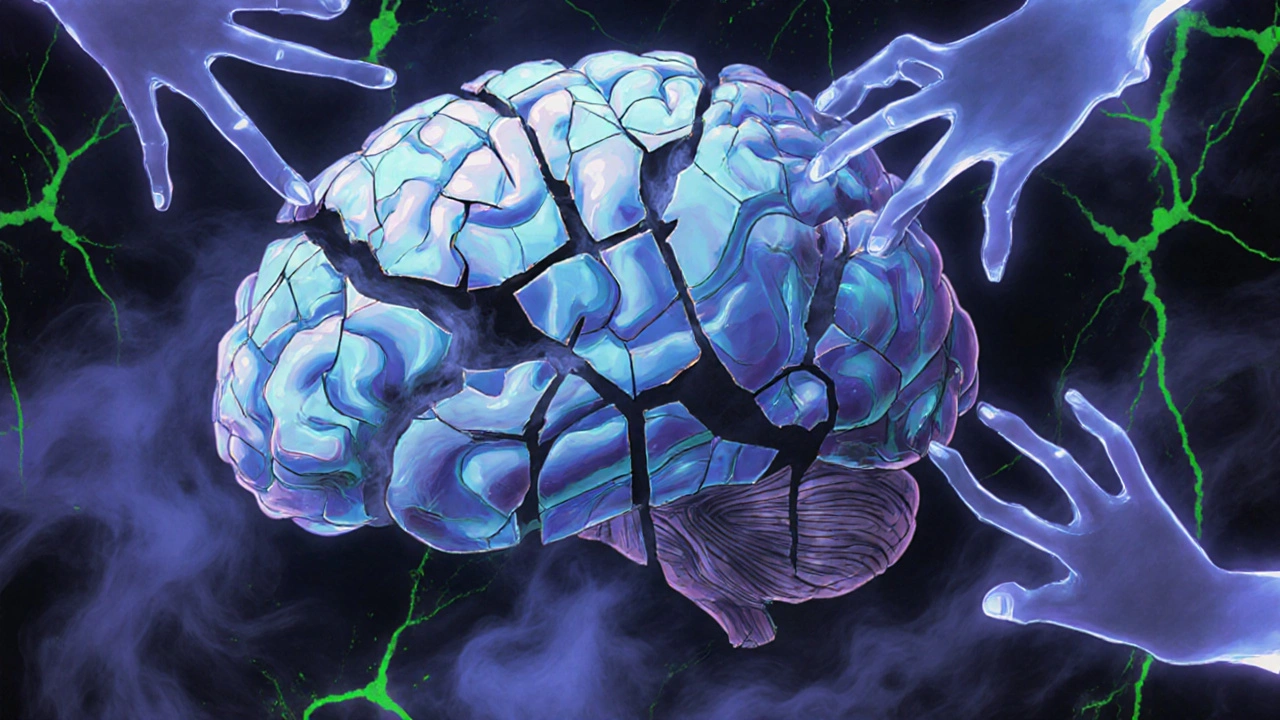

The most serious long-term effect of a medication overdose is brain injury caused by lack of oxygen. This happens when drugs like opioids or benzodiazepines slow or stop breathing. Even a few minutes without enough oxygen can kill brain cells. After four minutes, damage begins. After ten, the chances of full recovery drop sharply.

Survivors often describe it as ‘brain fog’ - a constant feeling of being slow, confused, or disconnected. Studies show 63% of overdose survivors have trouble with memory, either short-term or long-term. Nearly 57% struggle to concentrate. Simple tasks like remembering a phone number, following a conversation, or making a decision take much longer. Some lose the ability to balance properly, leading to falls. Others can’t speak clearly or hear as well as before.

It’s not just about memory. The chemicals in drugs like opioids, stimulants, and benzodiazepines change how brain cells communicate. One study found that 78% of overdose survivors had lasting changes in their neurotransmitter systems - the brain’s chemical messengers. These changes don’t heal on their own. They can lead to lifelong problems with mood, focus, and even personality.

Organ Damage Doesn’t Always Show Up Right Away

Overdose doesn’t just hurt the brain. It can wreck other organs, too - and sometimes the damage hides for days.

Take paracetamol (also called acetaminophen). It’s in hundreds of over-the-counter painkillers. Taking too much doesn’t make you sick right away. You might feel fine for 24 to 48 hours. But by then, your liver is already dying. In 45% of cases where treatment is delayed beyond eight hours, survivors end up with chronic liver disease - including cirrhosis. That means the liver can’t filter toxins, produce proteins, or store energy like it should. Many need lifelong medication or even a transplant.

Opioid overdoses often cause kidney failure. When breathing stops, blood pressure drops. The kidneys don’t get enough blood, and tissue starts to die. One study found 22% of non-fatal overdose survivors developed kidney problems that didn’t go away. Heart damage is also common. Opioids and stimulants can trigger abnormal heart rhythms. In 18% of cases, survivors face ongoing heart issues - high blood pressure, irregular beats, or weakened heart muscle.

And then there’s the lungs. When someone vomits during an overdose and can’t swallow or breathe properly, they can inhale stomach contents. That leads to pneumonia. In 6% of cases, this infection becomes chronic, requiring repeated antibiotics and hospital visits.

Mental Health Takes a Heavy Toll

Surviving an overdose isn’t just a physical trauma - it’s a psychological one. Nearly three out of four survivors develop a new mental health condition. Depression hits 38%. Anxiety disorders affect 33%. And 41% develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from the experience of nearly dying.

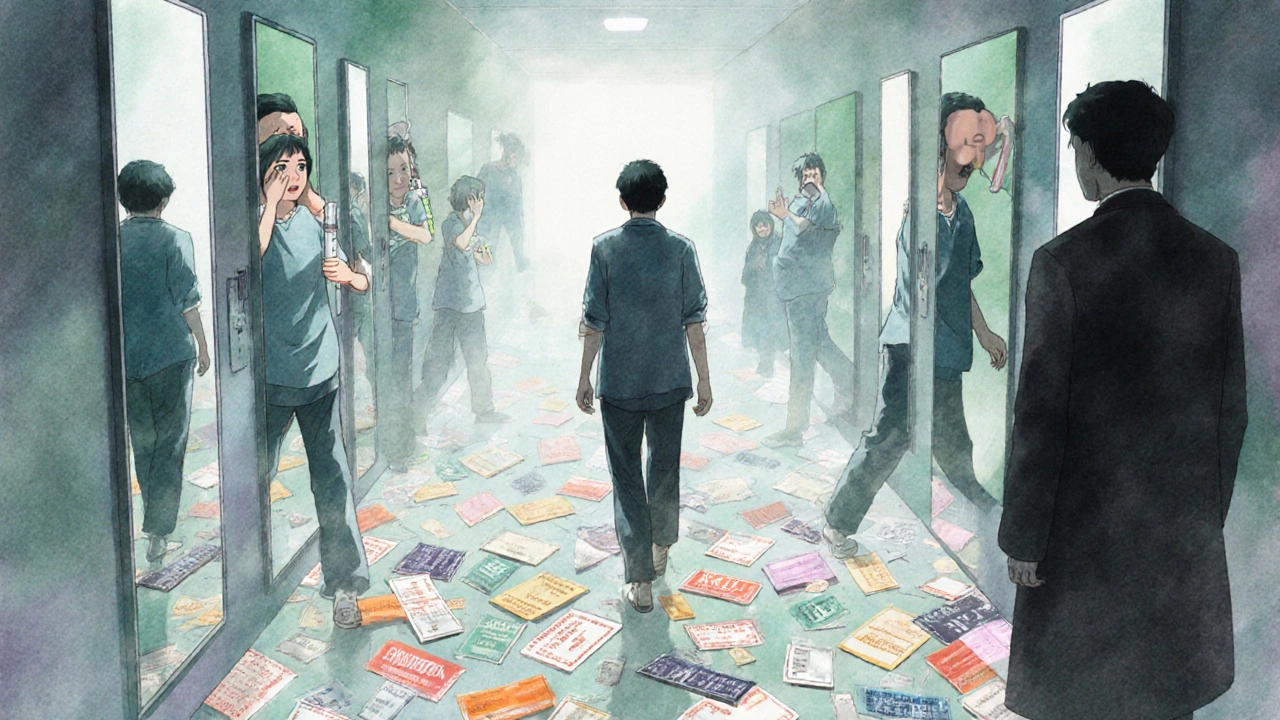

One person on a recovery forum said, “It’s been 18 months since I took 30 Xanax at once. My doctors say I’m lucky to be alive. But they don’t see how every day feels like walking through fog.” That’s not just a metaphor. Brain scans show real changes in the areas that control emotion and decision-making. The fear, guilt, and shame that follow an overdose can trap people in cycles of isolation and self-harm.

Worse, only 28% of survivors get proper mental health care within 30 days of being discharged. Many are sent home with a prescription for painkillers and no follow-up plan. Without therapy, counseling, or support, the emotional scars grow deeper. And those scars often lead back to drug use.

Delayed Treatment Makes Everything Worse

Time is everything in an overdose. For opioids, naloxone can reverse the effects - but only if given quickly. The CDC found that the average time between collapse and naloxone administration was over 11 minutes. In rural areas, it was nearly 23 minutes. By then, the brain has already been starved of oxygen for too long.

For paracetamol, the window to save the liver is just eight hours. Yet, 32% of people wait until symptoms appear - which can take two full days. By then, it’s often too late.

Even when people make it to the hospital, many are discharged without a plan. One report found that 41% of overdose survivors left the ER without being referred for follow-up care - no neurology check, no liver test, no mental health screening. That’s not negligence - it’s systemic failure. Emergency rooms are overwhelmed. Staff aren’t trained to look beyond the immediate crisis. And insurance doesn’t cover long-term monitoring.

The Hidden Cost of Survival

Surviving an overdose doesn’t mean you’re cured. It means you’re living with a chronic condition.

The lifetime cost of care for someone with permanent brain damage from an overdose averages over $1.2 million. That includes rehab, therapy, home modifications, lost wages, and ongoing medical care. For someone without lasting damage, it’s less than $300,000.

And the gaps in care are widening. Only 19% of U.S. hospitals have formal protocols to monitor long-term effects. Only 31% of counties offer specialized neurological rehab. In Australia, access is even more limited outside major cities. People in rural areas often travel hundreds of kilometers just to get a brain scan or a mental health appointment.

The government has started to act. In 2023, the U.S. allocated $156 million to study brain injury from overdoses. But experts say that’s less than a quarter of what’s needed. Without major changes, by 2030, only 22% of survivors will get the care they need.

What Can Be Done?

Prevention is the best solution. But for those who’ve already survived, early intervention saves lives - and brains.

- If you or someone you know overdosed, demand a neurological assessment within 72 hours.

- Ask for liver and kidney function tests - even if you feel fine.

- Get screened for depression, anxiety, and PTSD. These aren’t signs of weakness - they’re signs of trauma.

- Find a specialist who understands overdose recovery, not just addiction. Neurologists, psychiatrists, and rehab therapists who work with brain injury survivors can make a difference.

- Carry naloxone if you or someone you love uses opioids. Know the signs: unresponsiveness, slow breathing, pinpoint pupils.

Medication overdose isn’t a one-time mistake. It’s a medical event with lifelong consequences. The body doesn’t forget. The brain doesn’t reset. And without proper care, the damage just keeps growing.

Can you fully recover from a medication overdose?

Full recovery is rare. While some people regain most function with intensive rehab, permanent damage is common - especially to the brain and liver. Memory loss, trouble concentrating, balance issues, and mood disorders often last for years or permanently. The sooner treatment starts, the better the outcome - but complete recovery is not guaranteed.

How long does it take for brain damage from an overdose to show up?

Brain damage happens immediately during oxygen deprivation, but symptoms may take days or weeks to become obvious. Memory problems, confusion, or mood changes often appear slowly. Many survivors don’t realize something’s wrong until they struggle at work, forget names, or can’t focus on conversations. By then, the damage is already done.

Does paracetamol overdose always cause liver damage?

No - but only if treatment starts within eight hours. If you take too much paracetamol and get antidote treatment (N-acetylcysteine) in time, the liver can repair itself. But if you wait past eight hours, especially if you don’t feel sick, the risk of permanent liver damage jumps to 45%. Symptoms don’t appear until 48-72 hours later, which is why many people delay seeking help.

Why don’t doctors always check for long-term effects after an overdose?

Emergency rooms focus on saving lives, not preventing future problems. Most staff aren’t trained to screen for neurological or psychological damage. There’s no standard protocol in many hospitals. Insurance doesn’t always cover follow-up tests. And many survivors are discharged without a referral - even though studies show 63% need ongoing care. It’s a gap in the system, not a lack of awareness.

Can mental health issues from an overdose be treated?

Yes - but only if you get help. Therapy, medication, and support groups can significantly improve depression, anxiety, and PTSD after an overdose. However, many survivors don’t seek care because they feel ashamed, or because they’re told they’re “just lucky to be alive.” Mental health after overdose is treatable - but it’s often ignored.

Are there any new treatments for long-term damage from overdose?

New research is emerging. The National Institute on Aging is tracking 2,500 overdose survivors over 10 years to see how their brains age. Early results suggest overdose survivors may experience cognitive decline as if they’ve aged 7.3 extra years. Some clinics now offer specialized rehab programs combining physical therapy, cognitive training, and mental health support. But these programs are rare and mostly available in big cities.

What Comes Next?

If you’ve survived an overdose, your story isn’t over. The next chapter isn’t about guilt or blame - it’s about care. Your brain, liver, heart, and mind still need help. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. Don’t assume you’re fine because you’re breathing. The damage might be silent - but it’s real.

Ask for a full medical review. Get your brain checked. Get your liver tested. Talk to a therapist. Find a support group. You’re not alone. And you don’t have to live with this alone, either.

Lisa Detanna

November 23, 2025 AT 10:59My cousin survived an overdose last year. They told her she was lucky. But she still can’t remember her own birthday. No one talks about this part.

She’s 28. She used to run marathons. Now she forgets where she put her keys. And the doctors just shrug.

It’s not about addiction. It’s about brain damage. And we’re treating it like a moral failure.

Matthew Mahar

November 25, 2025 AT 08:55bro i had a friend do 40 xanax once and woke up in the er with no memory of the last 3 days

they said he was lucky but now he cant focus in meetings and keeps zoning out

he still takes benzos for anxiety lmao

its a trap

Demi-Louise Brown

November 26, 2025 AT 10:20Surviving an overdose is not the end of the story. It is the beginning of a long, often invisible, recovery process. The medical system is not designed to support long-term neurological and psychological recovery after acute events. This gap leaves survivors vulnerable to further decline.

John Mackaill

November 27, 2025 AT 21:19As someone who works in rural emergency services, I see this all the time. Naloxone gets administered, but then what? No follow-up. No neuro consult. No mental health screening. Just a discharge slip and a prescription for ibuprofen.

We save lives, but we don’t heal them.

Adrian Rios

November 28, 2025 AT 11:51I’ve been studying this for years. The brain doesn’t just recover like a scraped knee. When oxygen drops below a certain threshold, neurons don’t come back. They’re gone. And the chemical pathways that regulate mood, memory, and motor control? Rewired permanently.

It’s not ‘brain fog’-it’s neurodegeneration. And we’re calling it ‘luck’ because we don’t know how to fix it.

And then there’s the liver. Paracetamol isn’t ‘safe’ just because it’s in the medicine cabinet. It’s a silent killer. You don’t feel it until your liver is 70% dead.

And the mental health fallout? PTSD isn’t optional here. You nearly died. Your body knows it. Your brain remembers it. But no one asks you how you’re feeling after the IVs are pulled.

We treat overdoses like accidents. They’re medical catastrophes. And we’re failing people at every level.

Insurance won’t cover neuro rehab. Medicaid won’t pay for cognitive therapy. And if you’re not rich, you’re just supposed to ‘get over it’.

It’s not a personal failure. It’s a systemic one. And we’re letting people drown in silence.

Casper van Hoof

November 29, 2025 AT 07:50The ontological burden of survival, when framed through the lens of biomedical reductionism, reveals a profound epistemological deficit in contemporary emergency care paradigms. The body is rendered as a machine to be repaired, not as a phenomenological site of enduring trauma. The absence of longitudinal neurocognitive follow-up protocols reflects not merely logistical failure, but a deeper cultural denial of the embodied aftermath of pharmacological rupture.

Ragini Sharma

November 30, 2025 AT 07:59so i took 10 advil once bc i was mad and thought it was ‘safe’

turns out my liver was fine but i cried for 3 days straight

my therapist said that’s the brain trying to reboot

weird right?

Linda Rosie

November 30, 2025 AT 08:20Survival doesn’t equal recovery.

Vivian C Martinez

December 1, 2025 AT 08:55If you or someone you love has been through this, please don’t wait for symptoms. Get tested. Even if you feel fine. Your brain might be screaming, and no one else can hear it.

You deserve care. Not just second chances. Real care.

Ross Ruprecht

December 3, 2025 AT 07:26why are we even talking about this? people who OD are just weak.

if you don’t want to die, don’t take too much.

end of story.

Bryson Carroll

December 3, 2025 AT 09:19people who survive overdoses are just lucky they didn’t die and now they want trophies

the brain damage is their fault for being dumb

you think your ‘brain fog’ is tragic? try being a nurse who has to clean up after the same person every month

get over it

Jennifer Shannon

December 4, 2025 AT 02:12I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately-especially after reading that study about survivors aging 7.3 extra years cognitively. It’s not just about the drugs. It’s about how we treat people after they’re ‘saved.’

Imagine if you had a stroke and the hospital said, ‘You’re alive, go home, we’ll see you in a year if you get worse.’ That’s what we’re doing here.

And it’s not just the brain. The liver, the kidneys, the heart-they’re all whispering damage that no one listens to.

And then there’s the shame. People say, ‘You’re lucky to be alive,’ like that erases everything else. But you’re not lucky. You’re traumatized. And you’re alone.

Why do we celebrate survival but ignore the cost?

Because healing is expensive. And inconvenient. And it requires us to admit that this isn’t just about bad choices-it’s about broken systems.

And maybe, just maybe, if we stopped calling it ‘luck’ and started calling it ‘care,’ we’d actually do something about it.

Suzan Wanjiru

December 4, 2025 AT 15:17paracetamol overdose is the quiet killer

you feel fine for 2 days then boom liver gone

get your bloodwork done even if you think you're ok

it's not dramatic it's science

and yes your brain is still recovering even if you think you're fine

trust me i lived it

Kezia Katherine Lewis

December 6, 2025 AT 00:07Neuroinflammatory cascades triggered by hypoxic insult following pharmacological toxicity result in persistent dysregulation of glutamatergic and monoaminergic pathways, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. These alterations underpin the observed cognitive and affective sequelae, including executive dysfunction and emotional lability. Longitudinal neuroimaging studies confirm persistent structural atrophy in 68% of cases beyond 12 months post-overdose, independent of substance class. Current clinical protocols lack standardized neurocognitive screening tools, resulting in underdiagnosis and inadequate rehabilitation pathways.

Henrik Stacke

December 6, 2025 AT 02:21My sister survived a heroin overdose in 2019. She’s 32 now. She can’t drive at night anymore. She forgets people’s names. She cries for no reason. She says she’s ‘fine.’

We took her to a specialist last year. The neurologist said her brain looked like a 60-year-old’s.

She’s never used again. But the damage? It’s still there.

And no one talks about it. Not her friends. Not her family. Not the doctors who saved her.

They just say ‘you’re lucky.’

But luck doesn’t fix a brain.