If epigastric pain keeps popping up after meals, you might be dealing with a hidden food allergy. Below you’ll learn how to tell if your upper‑abdominal ache is allergy‑related, track the culprits, and put a plan in place so the discomfort stops getting in the way of your day.

Key Takeaways

- Epigastric pain can be an early sign of an IgE‑mediated or non‑IgE‑mediated food allergy.

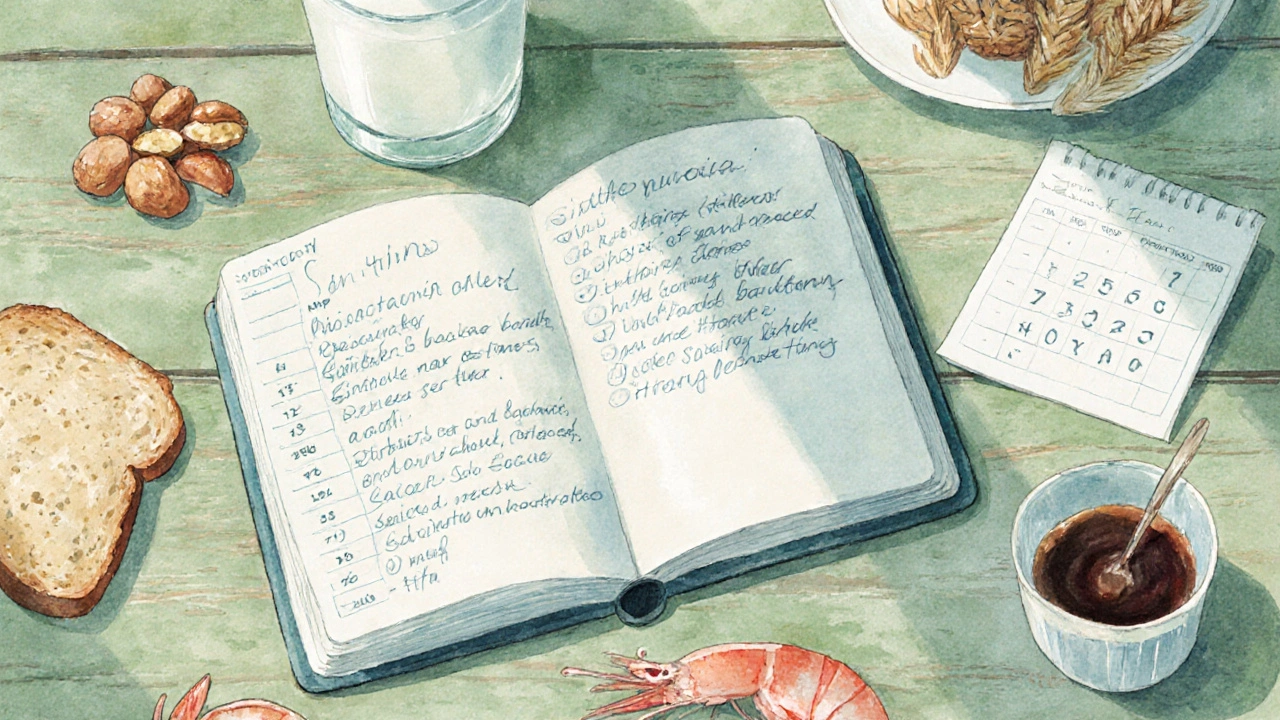

- Keeping a detailed food diary is the fastest way to spot patterns.

- Elimination diets, followed by controlled re‑introduction, reveal true triggers.

- Skin prick testing, serum IgE testing, and oral food challenges each have specific strengths.

- Professional guidance is essential when symptoms are severe or persist despite self‑management.

Understanding Epigastric Pain

Epigastric Pain is a discomfort located in the upper central region of the abdomen, just below the breastbone. It often feels like a burning, gnawing, or pressure sensation. While common causes include acid reflux, gastritis, and ulcers, food‑related allergic reactions can mimic or worsen these conditions by triggering mast‑cell degranulation and histamine release in the stomach lining.

The pain usually appears within minutes to a few hours after eating, and it may be accompanied by bloating, nausea, or early satiety. Because the symptoms overlap with many digestive disorders, pinpointing an allergy requires a systematic approach.

How Food Allergies Trigger Upper‑Abdominal Discomfort

Food Allergy refers to an immune‑mediated response that can be IgE‑mediated (classic allergy) or non‑IgE‑mediated (cell‑mediated). Both pathways can provoke the release of inflammatory mediators that affect the stomach’s smooth muscle and acid secretion, leading to the characteristic epigastric ache.

Common allergenic foods that often provoke upper‑abdominal symptoms include dairy, wheat, soy, eggs, nuts, shellfish, and certain food additives like sulphites or monosodium glutamate (MSG). Cross‑reactivity can also play a role; for example, a person allergic to birch pollen may react to apples, causing similar gut discomfort.

Spotting the Signs That Point to an Allergy

Not every case of epigastric pain is allergy‑related, but look for these red flags:

- Symptoms start shortly after eating a specific food and subside when the food is avoided.

- Accompanying signs such as itching, hives, swelling of lips or throat, or wheezing.

- Recurring episodes that don’t improve with typical acid‑suppressing medication.

- Family history of food allergies or atopic conditions (asthma, eczema).

If you notice two or more of these patterns, it’s worth digging deeper with a structured identification process.

Step‑by‑Step: Identify Your Triggers

- Start a food diary. Write down every bite, drink, and snack, the time you ate it, and any symptoms that follow. Include details such as portion size, cooking method, and added sauces.

- Look for clusters. After a week or two, review the diary for foods that consistently precede pain.

- Begin an Elimination Diet. Remove the suspected foods for 2-4 weeks while keeping the diary. Ensure you maintain balanced nutrition-consult a dietitian if needed.

- Re‑introduce foods one at a time. Every 3-5 days, add back a single food in a small portion and monitor symptoms. A clear reaction confirms the trigger.

- Consider diagnostic testing. If the diary and elimination diet point to a specific food but you need confirmation, discuss testing options with your doctor.

Diagnostic Tools: What Works Best?

| Test | What it measures | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin Prick Test | IgE antibodies on skin mast cells | Quick results (15‑20min), high sensitivity for many allergens | Possible false‑positives, requires skilled practitioner |

| Serum IgE Test | Specific IgE antibodies in blood | Can test multiple foods at once, safe for skin‑sensitive patients | Less sensitive for some foods, longer turnaround (days) |

| Oral Food Challenge | Clinical reaction to controlled food exposure | Gold‑standard for confirming true allergy | Time‑intensive, must be done under medical supervision due to risk of anaphylaxis |

Most clinicians start with a skin prick test or serum IgE test and reserve the oral food challenge for uncertain cases. Remember, a positive test does not always mean a symptomatic allergy; always correlate with your diary findings.

Managing the Pain Once Triggers Are Known

After you’ve nailed down the culprit, the goal shifts to prevention and symptom relief.

- Read labels carefully. Allergen information is mandatory in many countries, but watch for hidden sources (e.g., casein in processed meats).

- Plan meals ahead. Batch‑cook safe recipes and keep a list of “allergy‑friendly” restaurants.

- Use antihistamines (e.g., cetirizine) for occasional accidental exposures, but discuss dosage with a pharmacist.

- Consider a short course of proton pump inhibitors if acid reflux co‑exists; they won’t treat the allergy itself but can ease the burning sensation.

- Include probiotic‑rich foods (yogurt, kefir, fermented veggies) to support gut barrier function, which may reduce symptom severity.

For chronic sufferers, a registered dietitian can help design a nutritionally complete diet that avoids triggers while meeting calorie and micronutrient needs.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you experience any of the following, contact a healthcare provider promptly:

- Severe abdominal pain that wakes you from sleep.

- Signs of anaphylaxis: swelling of the face or throat, difficulty breathing, rapid heartbeat.

- Persistent pain despite a 4‑week elimination diet.

- Weight loss, vomiting, or blood in stools-these could indicate a more serious gastrointestinal condition.

A gastroenterologist can rule out ulcers, H.pylori infection, or gallbladder disease, while an allergist can confirm the immune‑mediated nature of your symptoms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can epigastric pain be caused by a food intolerance instead of an allergy?

Yes. Food intolerances (like lactose or fructose malabsorption) can also lead to upper‑abdominal discomfort, but they don’t involve the immune system. The key difference is that intolerances usually cause bloating, gas, or diarrhea without itching, hives, or rapid onset of symptoms.

How long should an elimination diet last?

A minimum of two weeks is recommended to clear existing allergens from the system, but many clinicians extend it to four weeks for clearer results, especially for delayed‑type reactions.

Is it safe to do a skin prick test at home?

No. Skin prick testing requires sterile equipment and professional interpretation of results. Improper technique can cause infection or false readings.

Do antihistamines help with epigastric pain?

They can reduce histamine‑driven inflammation and mild pain, but they won’t address acid‑related irritation. Use them under guidance, especially if you’re on other medications.

What’s the difference between a food allergy and a food sensitivity?

Allergies involve an immune response (IgE or cellular) and can cause systemic symptoms, while sensitivities are non‑immune reactions often linked to digestion or metabolic issues. Sensitivities usually produce milder, slower‑onset symptoms.

Rahul yadav

October 4, 2025 AT 02:01Oh wow, dealing with that gnawing epigastric ache can feel like a nightmare, but you’re definitely not alone – a solid food diary can be a game‑changer! 📓

Start jotting down every bite, sip, and even the spices you use, plus the time you felt that uncomfortable burn. It’s amazing how patterns emerge when you actually look at the data. You’ll be surprised to see that something as innocent‑looking as a flavored yogurt or a hidden gluten ingredient could be the culprit. Keep the entries consistent, and don’t forget to note any extra symptoms like itching or a slight hives flare – they’re key clues. Trust the process, stay patient, and you’ll be on your way to pinpointing the trigger. 💪

Dan McHugh

October 13, 2025 AT 17:33Sounds like a decent plan, but honestly, if you’re already on meds and still hurting, maybe it’s just stress. I’d keep the diary short and see if anything obvious pops up.

Sam Moss

October 23, 2025 AT 09:05Imagine the symphony of flavors dancing in your gut, only to be interrupted by an unintended allergic overture! 🎶 Your gut is basically a battlefield where histamines and acids spar, and the only way to call a truce is by getting the intel right. A food journal becomes your spy dossier – track the suspects, note the time‑to‑symptom latency, and watch for any bizarre accomplices like hidden MSG or sulfites. Don’t forget the power of re‑introduction; it’s the ultimate reveal, like a detective pulling the rug from under the villain. Keep it colorful, keep it consistent, and you’ll crack the case.

Suzy Stewart

November 1, 2025 AT 23:37Great tips! 👍 Staying on top of the diary and re‑introductions is the key. Also, don’t forget to double‑check those sneaky label ingredients – they love hiding in plain sight! 🙌

abhi sharma

November 11, 2025 AT 15:08Sure, skipping meals totally cures epigastric pain, right?

mas aly

November 21, 2025 AT 06:40I appreciate the empathy in the earlier comments and want to add that the timing of symptom onset can be a crucial data point. While diaries are helpful, be meticulous about noting the exact minute post‑meal when discomfort starts – this granularity often differentiates an IgE‑mediated reaction from a slower, non‑IgE process. Maintaining that precision doesn’t require extra effort, just a quick glance at the clock.

Abhishek Vora

November 30, 2025 AT 22:12Allow me to expand on the diagnostic hierarchy: skin prick testing remains the front‑line tool for rapid IgE detection due to its high sensitivity, particularly for allergens such as peanuts, tree nuts, and shellfish. However, its specificity can falter with cross‑reactive plant pollens, necessitating serum-specific IgE assays to quantify antibody titers for foods like apples in birch‑allergic patients. The oral food challenge, albeit resource‑intensive, is indisputably the gold standard, revealing true clinical reactivity that serologic tests might miss. In practice, a stepwise approach-starting with a detailed diary, followed by skin prick, then serum IgE, and finally a supervised challenge-optimizes both accuracy and safety.

maurice screti

December 10, 2025 AT 13:44When one first contemplates the labyrinthine nexus between dietary intake and epigastric discomfort, it becomes evident that the superficial notion of "just eat less spice" is woefully inadequate. The physiological orchestra within the upper abdomen, comprising gastric acid secretions, motility patterns, and immunologic surveillance, is exquisitely sensitive to a multitude of exogenous stimuli. It follows, therefore, that a methodical elicitation of causative agents demands a rigorously structured protocol. Commencing with an exhaustive chronicle of ingestion-cataloguing not merely the macronutrient composition but also the culinary additives, preparation methods, and even the attendant ambiance-lays the groundwork for subsequent inferential analysis. Subsequently, one must engage in a period of elimination, judiciously excising the suspected allergens whilst vigilantly preserving nutritional equilibrium; this phase, often spanning three to four weeks, serves to attenuate residual immunologic load. The re‑introduction phase, executed with calibrated minimal portions at staggered intervals, affords an empirical window through which the temporal correlation between exposure and symptomatology can be precisely observed. Moreover, it is incumbent upon the clinician to interpret these observations within the broader context of ancillary diagnostic modalities-skin prick testing, serum‑specific IgE quantification, and, when indispensable, supervised oral food challenges-each bearing its own spectrum of sensitivity and specificity. One must also remain cognizant of the potential confounders, such as stress‑induced hyperacidity or concurrent Helicobacter pylori infection, which may masquerade as allergenic phenomena. In summation, the pursuit of clarity in the realm of food‑induced epigastric pain is an endeavor that obliges both patient diligence and professional acumen, marrying empirical data with clinical insight to forge a path toward lasting relief.

Abigail Adams

December 20, 2025 AT 05:16Your expansive exposition, while thorough, borders on pedantry. The practical takeaway for the average sufferer is that a concise diary and a short elimination trial suffice; most patients lack the stamina for such a drawn‑out scientific treatise. Moreover, invoking every possible confounder dilutes actionable advice. In short, simplify, prioritize, and get results.

Belle Koschier

December 29, 2025 AT 20:47I think it’s great that we’re emphasizing practical steps. For those who might feel overwhelmed, breaking the process into bite‑size tasks-like logging just dinner for a week-can make it less daunting.

Allison Song

January 8, 2026 AT 12:19From a philosophical standpoint, the act of meticulous self‑observation mirrors the ancient practice of mindfulness; by attending to the minutiae of our meals, we cultivate a deeper awareness of the body's signals, fostering a harmonious relationship between consumption and well‑being.

Joseph Bowman

January 18, 2026 AT 03:51Now, while you’re all busy tracking calories, have you considered that food manufacturers might be inserting micro‑chips to monitor digestion? It’s all part of a larger agenda to control our health data. Stay vigilant.

Singh Bhinder

January 27, 2026 AT 19:23One thing I’m still curious about is how cultural dietary patterns influence the prevalence of these epigastric allergic responses. For instance, do regions with higher dairy consumption see more reports, or is it the processing methods?

Kelly Diglio

February 6, 2026 AT 10:54That’s an insightful query. Epidemiological data suggest a correlation between high dairy intake and increased incidence of IgE‑mediated milk allergies in certain populations, though confounding variables like genetic predisposition and early‑life exposure also play substantial roles.