When medications stop working for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), surgery isn’t a failure-it’s often the best path back to a normal life. For people with severe Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, surgery can mean the difference between constant pain and real relief. About 75% of Crohn’s patients and 15-30% of ulcerative colitis patients will need surgery at some point, according to the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. But what does that actually involve? And what happens after the operating room doors close?

What Surgery Looks Like for IBD

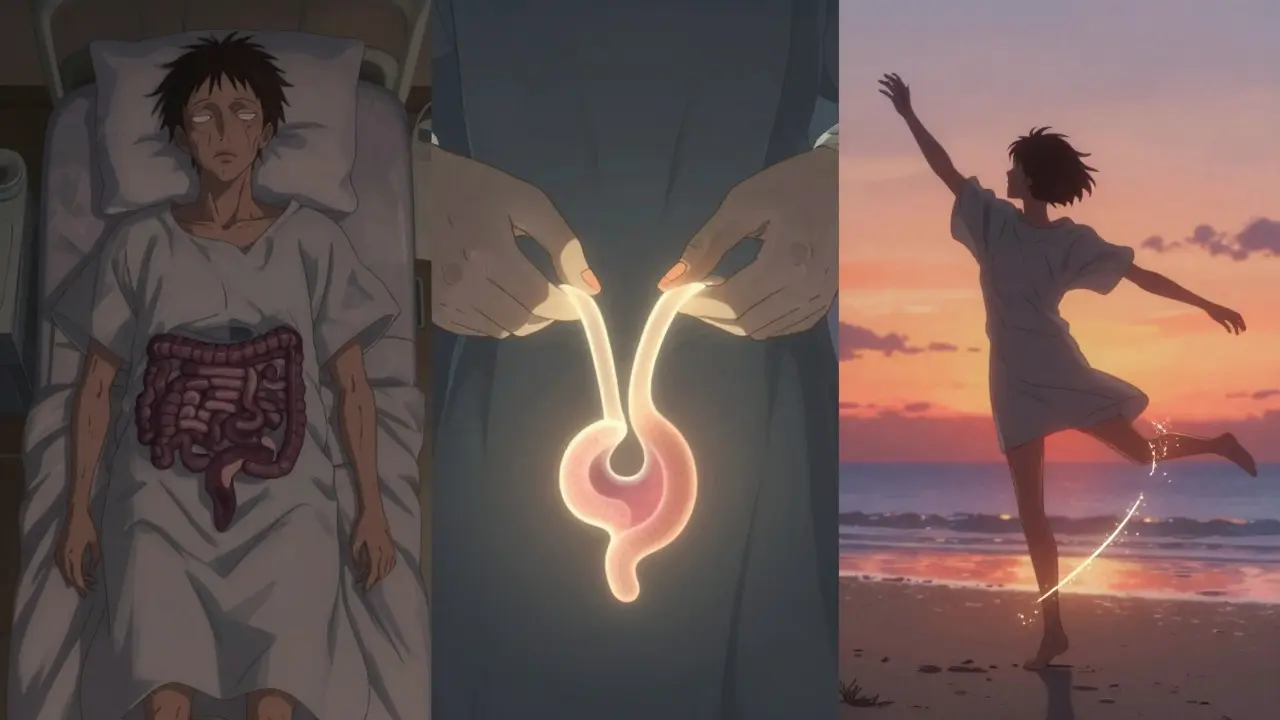

IBD surgery isn’t one-size-fits-all. It depends on whether you have Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis, where the disease is located, and how much of your bowel is damaged. The goal isn’t just to cut out bad tissue-it’s to remove disease while preserving as much function as possible.For ulcerative colitis, the most common surgery is a proctocolectomy-removing the entire colon and rectum. After that, there are two main options: an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), also called a J-pouch, or a permanent end ileostomy.

The J-pouch is made from the last 8-10 centimeters of your small intestine. It’s shaped like a J, stitched to your anus, and lets you pass stool normally again. It’s not a perfect replacement for a colon-your bowel movements will be more frequent, usually 4-8 times a day-but most people say it’s a huge improvement over constant diarrhea and bleeding.

For Crohn’s disease, surgeons avoid removing the entire colon unless absolutely necessary. Instead, they do a segmental resection, cutting out the diseased part of the bowel and reconnecting the healthy ends. If you have multiple strictures (narrowed sections) in one area, a strictureplasty might be done instead. This opens up the narrowed part without removing any bowel, helping prevent short bowel syndrome.

One key difference: J-pouch surgery is rarely done for Crohn’s disease. Studies show that up to 50% of Crohn’s patients who get a J-pouch end up with disease returning right around the pouch, forcing them to get a permanent stoma later. That’s why surgeons are much more cautious.

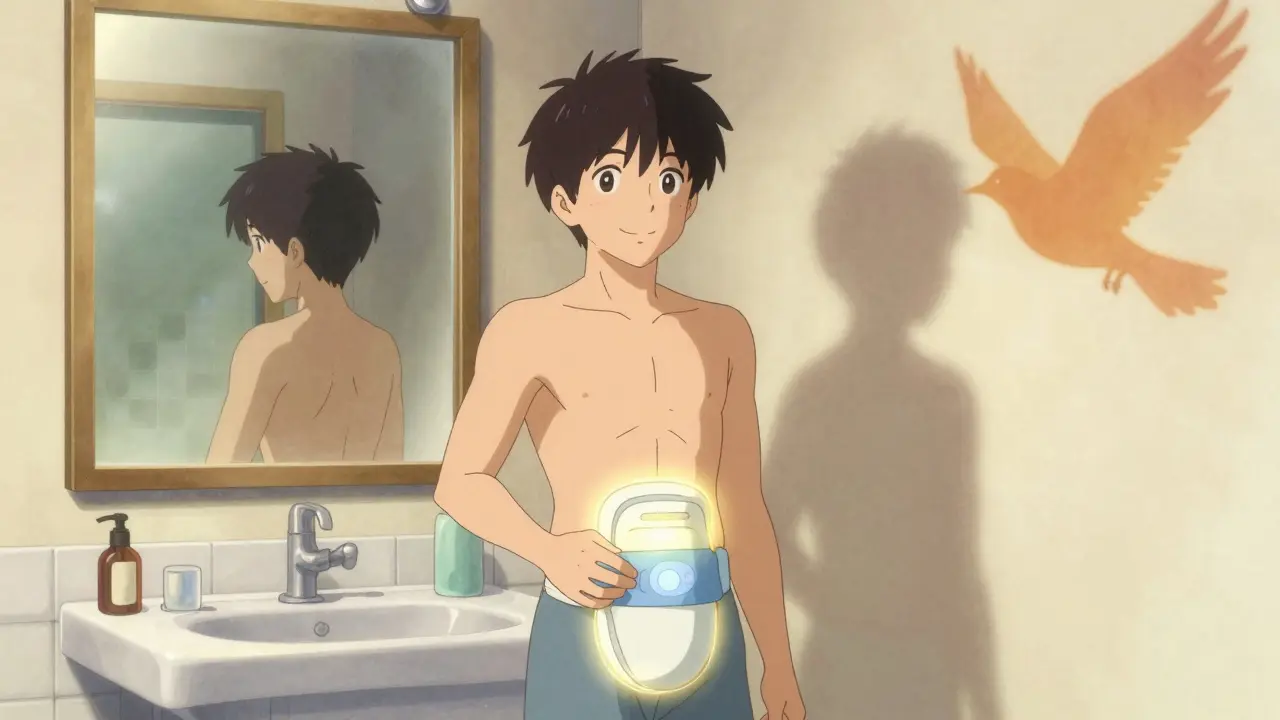

Understanding Ostomies

An ostomy is when your bowel is brought through your abdominal wall to create an opening-a stoma-for waste to exit your body. It’s temporary in some cases, permanent in others.The stoma itself is about the size of a quarter, sticking out 1-2 centimeters from your skin. Waste flows into a small, discreet bag that you empty 4-6 times a day. Modern ostomy bags are odor-proof, lightweight, and stick securely. Many people forget they have one after a few weeks.

Temporary ostomies are common in J-pouch surgery. After the colon and rectum are removed, the surgeon creates a temporary ileostomy to let the new pouch heal. It’s usually reversed 8-12 weeks later. This reduces the risk of a leak at the connection site, which can be life-threatening.

Permanent ostomies are needed when the rectum can’t be saved, or when a J-pouch isn’t safe. About 15-20% of ulcerative colitis patients end up with a permanent stoma, often because they’re older, have poor sphincter control, or have had multiple prior surgeries.

One thing many don’t tell you: living with an ostomy isn’t glamorous-but it’s liberating. On Reddit’s r/IBD community, 65% of people with permanent ostomies say they feel freer than before surgery. No more panic attacks before leaving the house. No more blood in the toilet. No more waiting for the next bathroom.

The Three-Stage Process for J-Pouch Surgery

Most J-pouch surgeries happen in three steps, not one. That’s because healing takes time, and doing it all at once increases risks.Stage One: The colon and rectum are removed. A temporary ileostomy is created. Hospital stay: 5-7 days.

Stage Two: About 8-12 weeks later, the surgeon builds the J-pouch and connects it to your anus. The temporary stoma stays in place. Hospital stay: 4-6 days.

Stage Three: After the pouch has healed (usually 2-3 months later), the temporary stoma is closed. You’re now passing stool through your anus again. Hospital stay: 3-5 days.

Some patients skip stage two and go straight from stage one to stage three, especially if they’re healthy and the surgeon feels confident. But the three-stage approach is still standard because it cuts the risk of a leak by nearly half.

Complications during any stage can include infection, bleeding, or a leak at the connection point. That’s why surgeons often recommend a temporary stoma-it gives the new connection time to heal without being stressed by stool passing through.

What Recovery Really Feels Like

Recovery isn’t just about healing wounds. It’s about relearning how your body works.After J-pouch surgery, you’ll have 6-10 bowel movements a day for the first few months. That drops to 4-8 over time. Nighttime seepage is common-about 32% of people use pads while sleeping. You’ll need to drink 8-10 cups of water daily to avoid dehydration. High-fiber foods like raw veggies, nuts, and popcorn are off-limits at first. You’ll learn what works for you through trial and error.

One of the biggest surprises? Pouchitis. About 40% of J-pouch patients get inflammation in their new pouch within the first year. It feels like a flare-up-diarrhea, cramps, fever. Most cases are treated with antibiotics like ciprofloxacin. A few people need long-term low-dose antibiotics to keep it under control.

For those with permanent ostomies, recovery is simpler but requires daily maintenance. You’ll need to learn how to change your bag, care for the skin around the stoma, and recognize signs of irritation or infection. Skin breakdown is common if the seal isn’t right. That’s why working with a certified wound, ostomy, and continence nurse (WOCN) before surgery is one of the best things you can do.

Success Rates and Long-Term Outcomes

Success isn’t just about surviving surgery-it’s about living well after.For ulcerative colitis patients with a J-pouch, 85-90% report being satisfied with their quality of life five years later. The pouch stays functional in 85-90% of cases after 10 years, according to the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. That’s a huge win for someone who spent years in pain.

For permanent ostomy patients, satisfaction is even higher-85% at five years. Why? Because there’s no risk of pouchitis, no need for repeat surgeries, and no fear of disease returning.

For Crohn’s disease, outcomes are more mixed. A segmental resection gives you 60-70% remission at five years. But by year 10, 80% will see disease come back somewhere else. That’s why maintenance therapy after surgery is critical.

One surprising stat: 68% of J-pouch patients are readmitted within 90 days after surgery. The most common reasons? Dehydration and pouchitis. Permanent ostomy patients have lower readmission rates-42%-but they face ongoing skin and appliance issues.

Who Shouldn’t Get a J-Pouch?

Not everyone is a candidate for a J-pouch. Some reasons it’s not recommended:- Women planning to get pregnant-fertility drops from 15% to 50-70% after IPAA surgery.

- Men concerned about sexual function-15-20% develop new erectile dysfunction.

- People with weak anal sphincters-can’t control stool after pouch is made.

- Patients over 70-higher risk of complications, longer recovery.

- Those with Crohn’s disease affecting the pouch area-too high a chance of recurrence.

These aren’t deal-breakers-they’re just trade-offs. If you’re young and healthy with no plans for kids, a J-pouch is often the best choice. If you’re older or have other health issues, a permanent stoma might be safer and simpler.

New Tech and What’s Coming Next

Surgery isn’t standing still. Robotic-assisted J-pouch procedures are now used at top centers like Mayo Clinic. They offer 20% shorter surgery times and 15% fewer complications than traditional laparoscopic methods.In 2023, the FDA approved the first smart ostomy bag-OstoLert by ConvaTec. It has sensors that alert you if it’s leaking or too full. It costs about $80, but many insurance plans cover it.

Researchers are also testing 3D-printed pouch designs tailored to each patient’s anatomy. Early trials at Cleveland Clinic show promising results in reducing complications.

One of the most exciting frontiers: microbiome transplants to prevent pouchitis. A National Institutes of Health study found that fecal transplants reduced pouchitis by 40% in the first year. It’s still experimental, but it could change how we manage long-term care.

What to Do Next

If you’re considering surgery, here’s what to do now:- Find a surgeon who specializes in IBD-not just general colorectal surgeons. Centers that do over 50 IBD surgeries a year have 35% fewer complications.

- Meet with a WOCN before surgery. They’ll teach you about ostomy care, show you products, and answer your fears.

- Join a support group. The United Ostomy Associations of America and Reddit’s r/IBD have thousands of people who’ve been where you are.

- Ask about your specific risks: How likely is a leak? What’s your chance of pouchitis? Will you need maintenance meds after?

- Don’t rush. Surgery is a big decision. Take time to understand your options.

Surgery for IBD isn’t the end of your story-it’s the start of a new chapter. It’s not easy. But for many, it’s the moment they finally get their life back.

Radhika M

December 16, 2025 AT 07:35Just had my J-pouch reversal last month. First 3 weeks were rough-6-8 bowel movements a day, always worried about leaks. Now? I can run 5Ks, swim, even wear jeans without panic. It’s not perfect, but it’s mine. Worth every second of recovery.

CAROL MUTISO

December 17, 2025 AT 01:48Let’s be real-ostomies are the unsung heroes of IBD survival. People act like it’s some tragic fate, but honestly? I’d rather have a bag I can empty than spend another Tuesday curled up on the bathroom floor. Modern bags? They’re basically invisible. I forgot I had one until my dog licked it and I realized-oh right, I’m a walking medical device now. And I’m fine with that.

Jessica Salgado

December 18, 2025 AT 11:43My surgeon said I was a ‘textbook candidate’ for the J-pouch-28, no kids, no sphincter issues. But then I read about pouchitis and started crying in the parking lot. I didn’t know 40% of people get it. I thought surgery was the end of the nightmare. Turns out it’s just the next level. I’m scared. Not of the surgery-of the after. Will I ever sleep through the night again? Will I be that person who smells like bleach and anxiety?

Martin Spedding

December 18, 2025 AT 23:21Y’all are overthinking this. J-pouch? Sure. But why not just go permanent? Less surgery, less risk, less drama. I’ve seen too many people go through 3 stages and end up with a stoma anyway. Waste of time. Just cut it all out. Done. Move on. Also, pouchitis is just lazy gut. Take antibiotics. Stop whining.

Raven C

December 19, 2025 AT 20:28While I appreciate the clinical overview, I must express profound concern regarding the casual normalization of ostomy life. The assertion that ‘many people forget they have one’ is not merely misleading-it is ethically irresponsible. The human body is not a machine to be retrofitted. To suggest that losing one’s natural physiology is ‘liberating’ is a dangerous rhetorical trope, one that erases the existential grief inherent in bodily alteration. I am not convinced this is progress-it is adaptation, yes, but at what cost to the soul?

Chris Van Horn

December 21, 2025 AT 07:57Actually, the data on J-pouch success rates is misleading. The 85-90% satisfaction rate? That’s based on patients who survived the first year. The real number-after 10 years-is closer to 55%. Also, the 3-stage process? Totally outdated. Robotic surgery allows for single-stage procedures now. You’re being sold a 1990s protocol by surgeons who refuse to update their CVs. And don’t even get me started on fecal transplants-those are just glorified poop injections. Science has moved on.

Peter Ronai

December 21, 2025 AT 19:43Everyone’s acting like this is some groundbreaking revelation. Newsflash: this has been standard since the 80s. And you’re all acting like you’re the first people to ever have IBD. I had my resection in 2007. No one talked about pouchitis back then because we didn’t have Reddit to whine on. Also, smart ostomy bags? That’s a gimmick. My bag from 1999 still works fine. You people are too soft.

Naomi Lopez

December 21, 2025 AT 22:27It’s funny how we all treat surgery like a finish line. It’s not. It’s a new starting line-where you learn your body’s new language. I used to think ‘normal’ meant no stoma. Now I know normal means no panic attacks. No blood. No hiding. The J-pouch isn’t perfect, but it’s mine. And I’m not sorry for it. I’m proud. I survived. That’s the real win.

Donna Packard

December 23, 2025 AT 16:17You’re not alone. I had my stage one last year. I cried for three days. But I also laughed with my mom when she asked if the bag looked like a ‘fanny pack.’ We’re going to be okay. One day at a time.