Transferring a prescription seems simple-just call the pharmacy, ask them to move it, and you’re done. But if you’ve ever waited days for a refill because the label was wrong, or had to go back to the doctor because the dose didn’t match what you were told, you know it’s not that easy. A single mistake on a prescription label can lead to a tenfold overdose, a dangerous drug interaction, or even death. In 2023, the DEA changed the rules to let pharmacies electronically transfer Schedule II prescriptions for the first time-but that’s just the start. Getting this right means understanding what goes on behind the scenes, how labels are built, and what you, as a patient, need to do to stay safe.

Why Prescription Labels Matter More Than You Think

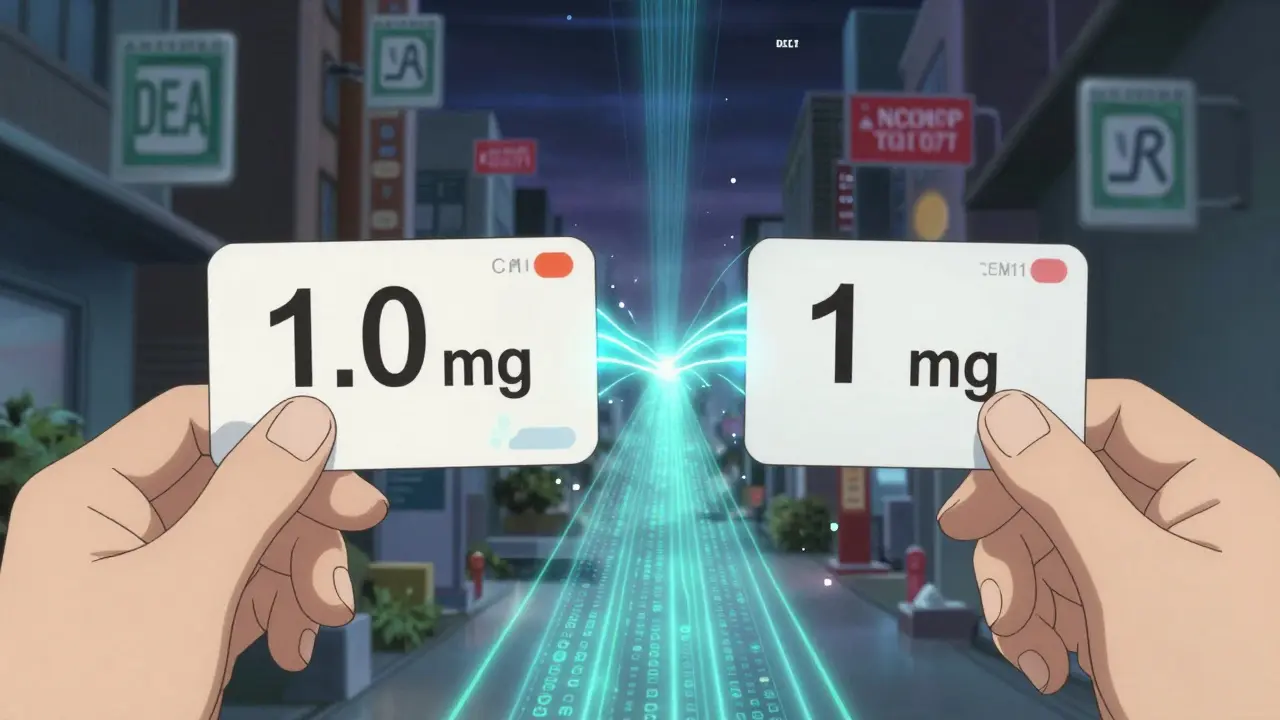

Prescription labels aren’t just paperwork. They’re your safety net. Every detail on that small piece of paper or digital screen has been chosen to prevent errors. The FDA requires specific information: your full name, the drug name, strength, dosage form, quantity, directions, prescriber’s name, prescription number, issue date, refill count, and pharmacy contact info. Sounds basic? It is. But even small mistakes break the system.Take trailing zeros. If a label says “1.0 mg” instead of “1 mg,” someone might misread it as 10 mg. That’s a tenfold overdose. Between 2018 and 2022, the FDA recorded 327 medication errors tied to this exact mistake. Or consider decimal points: “.4 mg” can look like “4 mg” if the dot is smudged. That’s why labels must use “0.4 mg”-leading zeros are non-negotiable. These rules exist because people die from them.

Another hidden danger? Units. The FDA requires metric measurements (milligrams, milliliters) for all drugs except insulin. Why? Because mixing up apothecary units (grains, drams) with metric caused 12% of dosage errors in hospitals in 2021. If your label says “10 mg” and you’re used to “1 grain,” you might think it’s the same. It’s not. That’s why labels now spell out units: “10 milligrams,” not “10 mg.”

How Prescription Transfers Work Now (2026 Rules)

Before August 2023, you couldn’t transfer a Schedule II prescription-like oxycodone or fentanyl-between pharmacies at all. If you moved, you had to get a new script from your doctor. Now, you can transfer it once, electronically. But only once. After that, you’re done. No refills can be transferred with it. That’s a big shift.For Schedule III to V drugs-like codeine cough syrup or anabolic steroids-you can transfer up to the number of refills left on the original. Non-controlled meds? Most states allow multiple transfers. But here’s the catch: electronic transfer is now the gold standard. The DEA bans converting prescriptions to fax or paper during transfer. The data must move digitally, unchanged.

That means the transfer system must carry every single piece of data: the original prescription date, the first fill date, remaining refills, the name and DEA number of both pharmacies, the pharmacist who sent it, the pharmacist who received it, and the transfer date. If one thing is missing, the prescription is invalid. No exceptions.

Most pharmacies use the NCPDP SCRIPT 2017071 standard. A 2022 University of Florida study found this system maintains 98.7% data accuracy. Fax? Only 82.3%. Phone? Just 76.1%. That’s why even if your pharmacy says they’ll call it in, they shouldn’t-for controlled substances, it’s not allowed anymore.

What Patients Must Do to Avoid Disaster

You’re not just a passive recipient. You’re part of the safety chain. Here’s what you need to do before you ask for a transfer:- Confirm the receiving pharmacy can fill it. Especially for Schedule II drugs-those can only be filled once. If the pharmacy doesn’t have stock, you’re stuck. Don’t assume they do. Call ahead.

- Don’t transfer without knowing your refill count. If you think you have three refills left but the original only had one, you’ll get turned away. Ask your old pharmacy for a printout before you go.

- Verify the label when you pick it up. Compare it to your old one. Does the dose match? Is the drug name spelled right? Are there any extra warnings? If something looks off, don’t take it. Ask the pharmacist to double-check.

Real stories show why this matters. In California, after a 2022 law allowed outsourcing pharmacies to dispense prescriptions, 23% of transfer attempts failed because patients didn’t check if the new pharmacy could handle the drug. One Reddit user in Melbourne described waiting five days for a pain med after transferring a Schedule II script-only to find out the new pharmacy didn’t stock it. They had to drive back to their old town.

On the flip side, users who used pharmacies with automated verification systems reported 99% success rates. These systems check inventory, match the DEA number, and flag mismatches before the transfer completes. Ask your pharmacy if they use this tech.

What Pharmacists Are Required to Do

Pharmacists aren’t just filling bottles. They’re auditors. When a prescription comes in, they must:- Confirm the electronic record matches the original exactly-no truncation, no edits.

- Record the transfer on the system: who sent it, who received it, when, and the DEA numbers of both pharmacies.

- Add the word “transfer” to the electronic record and note the original pharmacy’s details.

- For Schedule II prescriptions, mark that this was the one and only transfer allowed.

Wisconsin’s rules go further: they require the receiving pharmacist to write the transferring pharmacy’s name, address, and DEA number on the back of the invalidated original paper copy. Even if you never see that paper, it’s there.

Training matters. Pharmacists need about 8.5 hours of training to hit 95% compliance with the 2023 DEA rules. But turnover is high. The average pharmacy re-trains staff every 6.2 months because software updates change how transfers are logged. That’s why consistency is hard-especially in small, independent pharmacies.

Why System Glitches Still Happen

Even with perfect rules, technology fails. In 2022, the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 18% of pharmacies reported data truncation during transfers. That means part of the label-maybe the dosage or refill info-got cut off. It’s not always the pharmacist’s fault. It’s the software.Old pharmacy management systems don’t talk to new ones. If your old pharmacy uses a 2019 system and the new one uses 2024, the data might not map correctly. That’s why the industry is rushing to upgrade to SCRIPT 2024.07. Early adopters say it cuts transfer errors by over 60%.

And then there’s the rural gap. Only 41% of pharmacies in rural areas are connected to electronic transfer networks. If you live outside a city, you might still be stuck calling or faxing. That’s why prescription abandonment is 15% higher in these areas-patients give up when they can’t get their meds on time.

What’s Coming in 2025: The FDA’s PMI Rule

The next big change is the FDA’s Patient Medication Information (PMI) rule, set to roll out fully in 2025. It’s not just about transfers anymore. It’s about how labels are written for you.Under PMI:

- All prescription labels must use plain language-no medical jargon like “HCTZ” or “MOM.” Write “hydrochlorothiazide” and “magnesium oxide mixture.”

- Drug purpose must be included: “for high blood pressure,” not just “take one daily.”

- Labels must be printed on paper by default. Digital versions are optional-you have to ask for them.

- Pharmacies must use automated scanners that check labels for errors before you leave: wrong dose, missing warning, trailing zero, mismatched name.

Dr. Michael Cohen of ISMP says this could prevent 30% of the 500,000 medication errors caused by misread labels every year. It’s not just better design-it’s a safety net built into the label itself.

Implementation will cost pharmacies $12,500 to $18,750 per location. But the alternative-wrong doses, ER visits, deaths-is far costlier.

What You Can Do Today to Stay Safe

You don’t need to wait for 2025. Here’s your action plan:- Always ask for a printed copy of your prescription before transferring it. Keep it.

- Call the new pharmacy before you go. Ask: “Can you fill this prescription? Does it have refills left? Is it a controlled substance?”

- When you get the new label, compare it to your old one. Do the numbers match? Is the drug name spelled the same? Are the directions identical?

- If something feels off, say so. Ask the pharmacist to check with the original pharmacy.

- Use pharmacies with barcode scanning and automated verification. Ask if they use NCPDP SCRIPT 2017071 or newer.

Medication safety isn’t about trusting the system. It’s about checking it. Every time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I transfer a Schedule II prescription more than once?

No. Under the DEA’s 2023 rule, Schedule II prescriptions (like oxycodone or fentanyl) can only be transferred once, electronically, between retail pharmacies. After that, no further transfers are allowed. If you need another refill, you must get a new prescription from your prescriber.

Why can’t I just fax my prescription to the new pharmacy?

For Schedule II drugs, faxing is prohibited under the 2023 DEA rule. Electronic transfer via NCPDP SCRIPT is the only legal method. For Schedule III-V drugs, fax or phone transfers are still allowed-but they’re less accurate. Fax transfers have a 17.7% error rate compared to 1.3% for electronic transfers. Always prefer electronic.

What if the new pharmacy gives me a label with “1.0 mg” instead of “1 mg”?

Do not take it. Trailing zeros (like 1.0 mg) are a known cause of tenfold dosing errors. The FDA requires all whole-number doses to be written without decimal points-so “1 mg” is correct, “1.0 mg” is not. Ask the pharmacist to correct it immediately. If they refuse, contact your state pharmacy board.

Do I need to bring my old prescription bottle to the new pharmacy?

You don’t have to, but it helps. The pharmacy needs the prescription number and prescriber details to verify the transfer. If you have the bottle, it gives them the exact info they need. If you don’t, they can still retrieve the record electronically-but only if the original pharmacy is connected to the network.

What should I do if my transfer fails?

First, confirm with your old pharmacy that the prescription is still active and has refills left. Then call the new pharmacy and ask what error they received. Common reasons: mismatched DEA number, system incompatibility, or no remaining refills. If the issue is technical, ask them to try again using a different system or contact the original pharmacy directly. If it’s a refill issue, you’ll need to contact your prescriber.

Juan Reibelo

January 24, 2026 AT 04:13Just transferred my oxycodone script last week-followed every step. Called the new pharmacy, confirmed stock, double-checked the label. Got it right on the first try. Still, my hands were shaking when I picked it up. One decimal point out, and I could’ve been in the ER. This post? Lifesaver.

Always keep the old bottle. Even if they say they have the record, they don’t. Trust me.

Darren Links

January 25, 2026 AT 00:00So now the feds are making us all pharmacists? Next they’ll be requiring us to memorize NCPDP standards before we can buy Tylenol. This is tyranny dressed up as safety. I’ve been taking pills for 20 years and never once needed a lecture on trailing zeros. Let people live.

Kevin Waters

January 26, 2026 AT 10:25Great breakdown! I work in pharmacy tech and can confirm: the SCRIPT 2017071 system is rock solid when implemented right. The real issue? Staff turnover and outdated software. I’ve seen transfers fail because one pharmacy was still on a 2015 system and the other was on 2024. No one’s at fault-it’s just tech lag.

Pro tip: If your pharmacy says ‘we’ll call it in,’ push back. For controlled substances, that’s not just sloppy-it’s illegal now. Ask if they use barcode verification. If they don’t, consider switching.

Himanshu Singh

January 27, 2026 AT 15:16Life is a balance, no? We want safety, but we also want ease. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s trying. 🙏

My uncle in Delhi had a bad experience with a wrong dose-now he checks every label like it’s a sacred text. Maybe that’s the real lesson: we’re not passive. We’re the last line of defense. Be the checker. Not the victim.

Stay calm. Stay aware. You got this.

Jamie Hooper

January 28, 2026 AT 21:03so like… uhh… the whole trailing zero thing? yeah i get it but like… who actually misreads 1.0 mg as 10 mg? like… is this real? or just some bureaucrat’s fever dream? i mean, come on. people arent that dumb. right? 😅

Husain Atther

January 29, 2026 AT 11:37The precision in this post is admirable. It reflects a deeper truth: healthcare systems function best when individuals are informed participants, not passive recipients. The data is clear-errors drop when patients verify. The technology exists. The rules are in place. What’s missing is consistent vigilance.

It’s not about distrust. It’s about responsibility. And that responsibility is shared.

Helen Leite

January 31, 2026 AT 10:13EVERYONE KNOWS THE PHARMACIES ARE IN BED WITH BIG PHARMA. They don’t want you to know how easy it is to mess up your meds. That’s why they made you check everything. It’s not to help you-it’s to cover their butts. And now they’re forcing you to use scanners? LOL. What’s next? A fingerprint scan just to get ibuprofen? 💀

Marlon Mentolaroc

February 2, 2026 AT 03:30Let’s be real-this whole ‘electronic transfer’ thing is a cost-cutting measure disguised as safety. The real reason faxing was banned? It’s cheaper to automate than to hire more staff to verify faxed scripts. The error rates? Correlated with staffing levels, not technology.

And don’t get me started on ‘plain language’ labels. You think ‘hydrochlorothiazide’ is easier than ‘HCTZ’? Try reading that on a 4mm pill bottle. This isn’t safety. It’s performative regulation.

Gina Beard

February 2, 2026 AT 08:35Labels are mirrors. They reflect who we are as a society: careful, or careless.

It’s not about the zeros. It’s about the silence before the mistake.

Don Foster

February 3, 2026 AT 12:33Anyone who thinks this is new needs to read the 1998 FDA Medication Error Guidelines. The trailing zero thing? Been standard since 2002. The electronic transfer mandate? Just catching up to Canada and the UK who’ve had it since 2010. This post reads like a press release written by a pharmacy intern who just discovered Google. The real story is how slow the US system is to adapt. Not how dangerous it is.

Also-NCPDP SCRIPT 2024.07? That’s not even out yet. Stop pretending you know what you’re talking about.

siva lingam

February 4, 2026 AT 19:11so you spent 2000 words telling people to read the label

congrats

you won the internet