DRESS syndrome is one of the most dangerous drug reactions you’ve never heard of - until it’s too late. It doesn’t strike quickly like an allergic rash. It creeps in weeks after you start a new medication, often mimicking the flu, then explodes into a full-body crisis. Fever. Swollen lymph nodes. A widespread rash. Liver failure. And in 1 out of 10 cases, death. This isn’t a rare curiosity - it’s a hidden killer hiding in plain sight, especially among people taking common drugs like allopurinol or carbamazepine.

What DRESS Syndrome Actually Looks Like

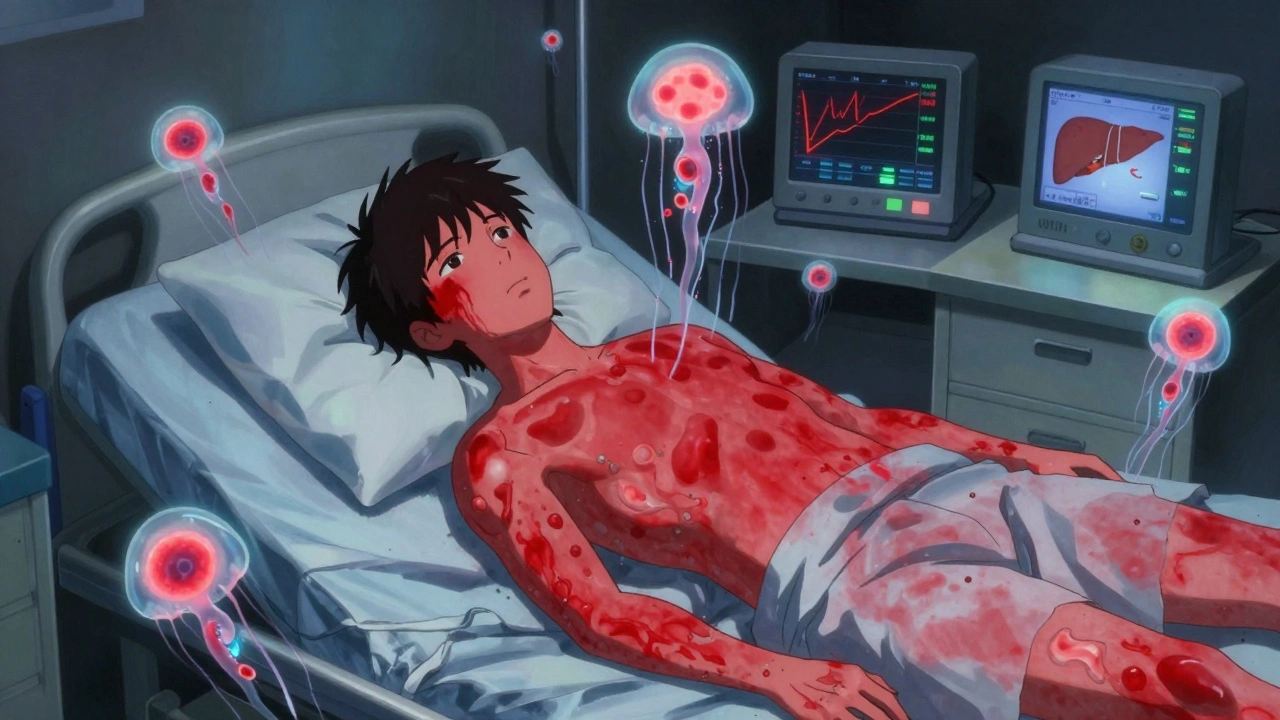

DRESS doesn’t start with a simple itch. It begins with fatigue, a low-grade fever, and a sore throat - symptoms you might blame on a cold or the flu. Then, 2 to 8 weeks after starting a new medication, the real signs appear. A red, flat, measles-like rash spreads across your torso, arms, and face. Your lymph nodes swell. Your temperature spikes above 38°C. And your blood test shows something strange: too many eosinophils.

Eosinophils are white blood cells that normally fight parasites. In DRESS, they go haywire, attacking your organs. Up to 90% of patients have them in dangerous numbers - over 1,500 per microliter. That’s not just a lab anomaly. It’s a warning sign your body is turning on itself.

But the rash is just the tip. The real danger is inside. Your liver takes the hardest hit. In 70% to 90% of cases, liver enzymes like ALT and AST spike above 1,000 U/L - sometimes over 2,800. Your kidneys may fail. Your lungs swell. Your heart beats irregularly. Some patients develop thyroid problems, diabetes, or even autoimmune diseases like Graves’ disease months after the rash clears.

Which Drugs Trigger DRESS?

Not every drug causes this. But a few are notorious. Allopurinol - the common gout medication - is responsible for nearly half of all DRESS cases. The risk skyrockets if you have kidney disease. In people with an eGFR below 60, one in every 200 allopurinol users develops DRESS.

Antiepileptic drugs like carbamazepine, phenytoin, and lamotrigine are next on the list. These are often prescribed for seizures, bipolar disorder, or nerve pain. Sulfonamide antibiotics like sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Bactrim) are also common triggers, especially in HIV-positive patients.

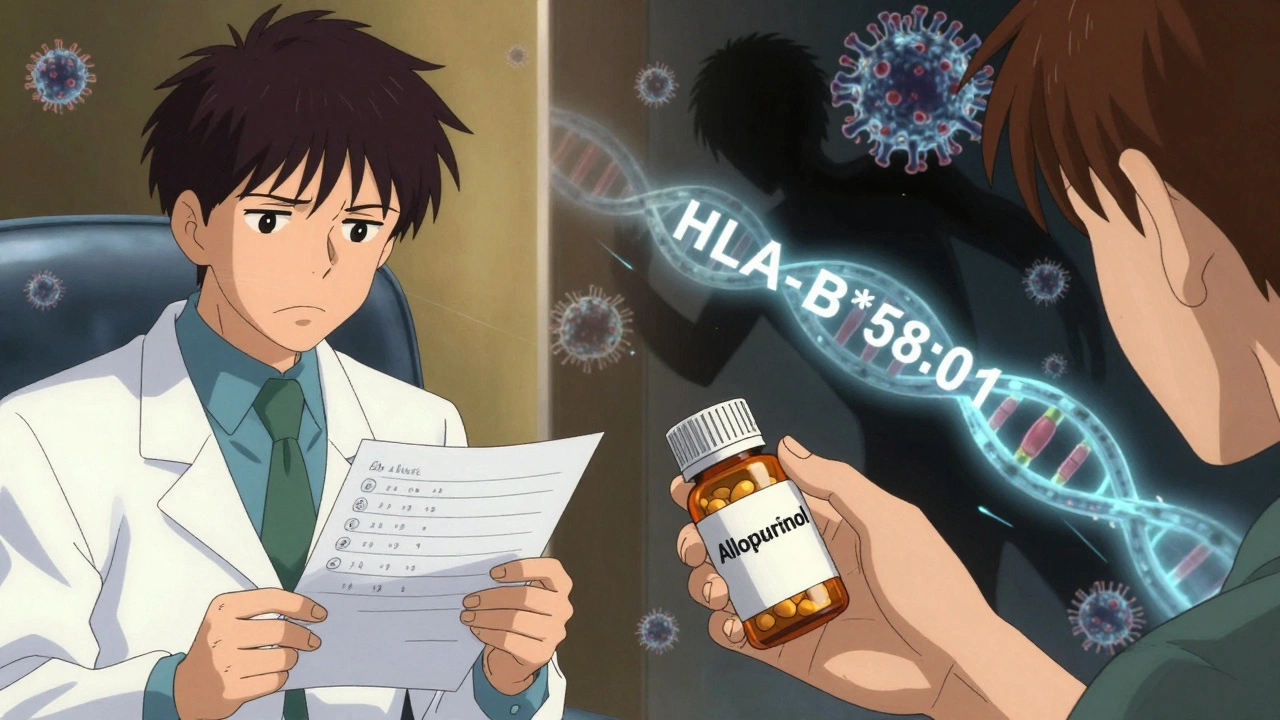

What makes these drugs dangerous? It’s not the dose. It’s your genes. If you carry the HLA-B*58:01 gene variant - common in people of Asian, African, or Hispanic descent - your risk of allopurinol-induced DRESS jumps 55-fold. That’s why Taiwan now requires genetic testing before prescribing allopurinol. Since 2015, DRESS cases from allopurinol dropped by 75% there.

DRESS vs. SJS and TEN: Why It’s Different

People often confuse DRESS with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN). All three are severe drug reactions. But they’re not the same.

SJS and TEN show up fast - within 1 to 4 weeks. They cause blistering, skin peeling, and massive mucous membrane damage. Up to 40% of TEN patients die. DRESS? It shows up later. The skin doesn’t peel off. Instead, it’s a flat, red rash. Mucosal damage happens in only 30% to 50% of cases. But DRESS attacks your internal organs. And it doesn’t end when the rash fades.

Here’s the kicker: DRESS is often tied to a hidden viral reactivation. In 60% to 70% of cases, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) wakes up 2 to 4 weeks after symptoms start. This isn’t just a coincidence. The virus may be fueling the immune chaos, making the reaction worse and longer-lasting.

How Doctors Diagnose It - And Why It’s So Hard

There’s no single blood test for DRESS. Diagnosis relies on a checklist called the RegiSCAR criteria. You need hospitalization plus at least three of these:

- Acute skin rash

- Fever over 38°C

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Eosinophilia (over 1,500 cells/μL or 10% of white blood cells)

- Atypical lymphocytes in the blood

- Organ involvement (liver, kidney, lungs, heart, etc.)

Here’s the problem: most doctors don’t think of DRESS. A 2020 study found only 35% of internal medicine residents could correctly identify it. Patients often see three or more doctors before getting the right diagnosis. One patient on a rare disease forum spent 6 weeks in limbo, her liver enzymes climbing, before a dermatologist finally connected the dots.

Doctors who miss DRESS often mistake it for a viral infection, mononucleosis, or even lupus. The key clue? Timing. If you got sick 3 to 6 weeks after starting a new drug - especially allopurinol or an antiseizure med - DRESS should be on the table.

What Happens If You Don’t Act Fast

Delay kills. If you keep taking the drug after symptoms start, your chance of dying jumps from 5% to 15%. The longer you wait, the more your organs are damaged. Liver failure can become irreversible. Kidney damage may need lifelong dialysis. Some patients develop chronic autoimmune conditions years later.

One patient, SarahR87, shared her story on the National Organization for Rare Disorders forum. After starting allopurinol for high uric acid, she developed a rash and fever. Her doctors thought it was a virus. Her AST hit 2,840 U/L - more than 50 times normal. She spent 45 days in the hospital. She survived. But her liver never fully recovered.

That’s why the first rule is non-negotiable: stop the drug immediately. Don’t wait for a diagnosis. If you’re on allopurinol, carbamazepine, or Bactrim and you develop a fever and rash after 2 weeks, stop the medication and go to the ER.

Treatment: Steroids, Support, and Survival

Once the drug is stopped, treatment begins. Most patients need hospitalization - often in intensive care. The main weapon? Corticosteroids. Prednisone or methylprednisolone at 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight daily. That’s usually 40 to 80 mg a day. Treatment lasts 4 to 8 weeks, then tapers slowly. Stopping too soon can cause a rebound.

Supportive care is just as critical. You need daily blood tests to track liver enzymes, kidney function, and eosinophil counts. Infection control is vital - your skin is compromised, and your immune system is overwhelmed. Bacteria like MRSA and fungi like Candida can invade. Antibiotics and antifungals are often needed.

For the most severe cases, newer treatments are emerging. In 2022, a study showed anakinra - a drug used for rheumatoid arthritis - cut hospital stays from 18.5 days to 11.2 days when added to steroids. Tocilizumab, another immune-modulating drug, is now being tested in clinical trials for steroid-resistant DRESS.

Long-Term Risks and What Comes After

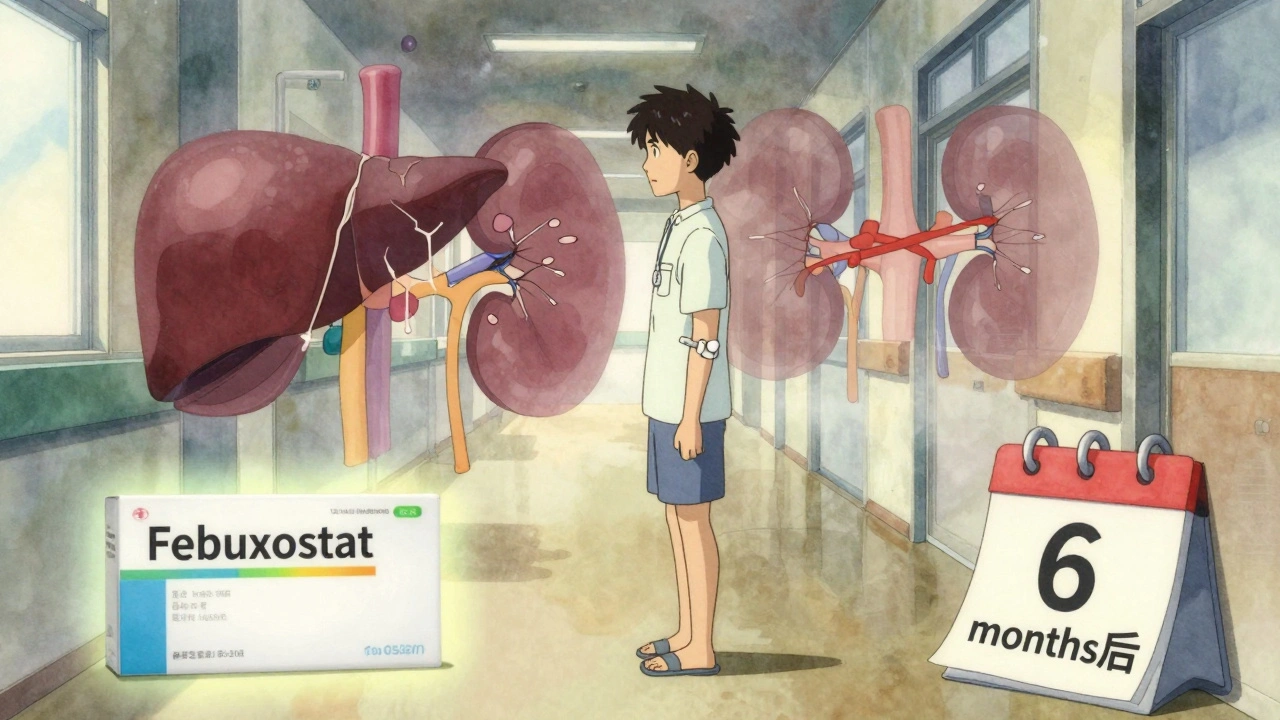

DRESS doesn’t disappear when the rash fades. About 20% to 30% of survivors have lasting organ damage. Kidney function may never return to normal. Thyroid problems like Hashimoto’s or Graves’ disease can appear months later. Some patients develop type 1 diabetes or autoimmune hepatitis.

A 2022 survey of 150 DRESS survivors found 27% needed ongoing nephrology care. Another 15% required endocrine follow-up. That’s why long-term monitoring is part of recovery. You need blood tests every 3 to 6 months for at least a year - and sometimes longer.

And here’s something rarely discussed: you may never be able to take the triggering drug again. Even a tiny amount can restart the reaction. That means if you had DRESS from allopurinol, you can’t use it again. Your doctor will switch you to febuxostat - a safer alternative for gout - especially if you have kidney disease.

How to Protect Yourself

If you’re prescribed allopurinol and you’re of Asian, African, or Hispanic descent, ask for HLA-B*58:01 testing before starting. It’s a simple blood test. If you’re positive, your doctor can choose a different medication. In the U.S., this isn’t standard yet - but it should be.

If you’re on any of these drugs - allopurinol, carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine, or sulfonamides - know the warning signs: fever, rash, swollen glands, fatigue. If they appear after 2 to 8 weeks, don’t wait. Stop the drug. Call your doctor. Go to the ER.

And if you’ve had DRESS before? Tell every doctor you see. Put it in your medical record. Wear a medical alert bracelet. This isn’t just a one-time event. It’s a lifelong risk.

DRESS is rare. But it’s not mysterious. It’s predictable. And with awareness, it’s preventable. The next time someone says, ‘It’s just a rash,’ remember - sometimes, it’s not.

What is the most common drug that causes DRESS syndrome?

Allopurinol is the most common trigger, responsible for 40% to 50% of DRESS cases. The risk is especially high in people with chronic kidney disease. Other common culprits include carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine, and sulfonamide antibiotics like Bactrim.

How long after taking a drug does DRESS syndrome appear?

Symptoms typically begin 2 to 8 weeks after starting the drug. In some cases, it can take as little as 1 week or as long as 16 weeks. This long delay is why DRESS is often missed - doctors rarely connect the rash to a medication taken weeks earlier.

Is DRESS syndrome fatal?

Yes. DRESS has a mortality rate of about 10%, mostly due to liver failure or severe infection. Early diagnosis and stopping the offending drug can reduce the risk to less than 5%. Delayed treatment increases the chance of death significantly.

Can DRESS syndrome come back after recovery?

The syndrome itself doesn’t return - but if you take the same drug again, even in tiny amounts, it can trigger a new, often more severe episode. Avoid all drugs linked to your previous DRESS reaction. Cross-reactivity with similar drugs is common.

Are there genetic tests for DRESS syndrome?

Yes. For allopurinol-induced DRESS, testing for the HLA-B*58:01 gene variant is highly reliable. People with this gene have up to a 55-fold higher risk. Screening is now standard in Taiwan and recommended for high-risk populations in the U.S. No routine genetic test exists for other DRESS triggers yet.

What should I do if I suspect I have DRESS syndrome?

Stop the suspected medication immediately. Go to the emergency room. Tell them you suspect DRESS syndrome - mention the drug you started, when you started it, and your symptoms (fever, rash, swollen glands). Request blood tests for eosinophils, liver enzymes, and kidney function. Early intervention saves lives.

Can DRESS syndrome cause long-term organ damage?

Yes. About 20% to 30% of survivors experience lasting damage, especially to the liver or kidneys. Some develop autoimmune diseases like Graves’ disease or type 1 diabetes months or years later. Lifelong monitoring may be needed, even after full recovery.

Is there a cure for DRESS syndrome?

There’s no cure, but it’s highly treatable. Stopping the drug and using corticosteroids can lead to full recovery in most cases. Newer drugs like anakinra and tocilizumab are showing promise for severe or resistant cases. The goal is to control the immune response before organs are permanently damaged.

dan koz

December 3, 2025 AT 21:19Man, I just got prescribed allopurinol last month for gout. Had no idea this could happen. My cousin died from something like this back in 2018 - they thought it was hepatitis. Never even connected it to meds. Scary as hell.

Kevin Estrada

December 5, 2025 AT 11:36OMG I KNEW IT. I TOLD MY DOCTOR THIS WASN'T JUST A RASH. She laughed at me. Said I was ‘overreacting like a hypochondriac.’ Guess what? Two weeks later I was in ICU with AST at 3100. They finally admitted it was DRESS. Now I’m on a medical alert bracelet and I’m not even mad - I’m just done trusting doctors who don’t Google.

Katey Korzenietz

December 6, 2025 AT 10:51Ugh. I hate when people say ‘it’s just a rash.’ Like your skin is some kind of disposable wallpaper. This is a SYSTEMIC REACTION. And if you’re Black or Asian and on allopurinol? You’re basically playing Russian roulette with your liver. Someone should sue the pharma companies for not warning people.

Ethan McIvor

December 7, 2025 AT 06:43It’s wild how medicine still treats genetics like an afterthought. We test for everything from BRCA to cystic fibrosis, but if you’re Nigerian or Filipino and get prescribed allopurinol? ‘Here you go, hope you’re lucky.’ We know the gene. We know the risk. We just don’t act like it matters unless it’s expensive. 😔

Mindy Bilotta

December 9, 2025 AT 00:50My sister had DRESS from lamotrigine. Took 6 months to get diagnosed. She’s fine now but still gets dizzy if she’s stressed. She carries a card in her wallet that says ‘DRESS SURVIVOR - DO NOT RE-EXPOSE TO ANTIEPILEPTICS.’ Smart move. You should too.

Brian Perry

December 9, 2025 AT 04:17Okay so here’s the thing - why is this not on every med bottle? Like, imagine if every antibiotic had a big red warning: ‘WARNING: MAY CAUSE YOUR BODY TO EAT YOUR LIVER 3 WEEKS LATER.’ Would you still take it? Probably not. But we don’t get that. We get ‘take once daily’ and a tiny footnote in 6pt font. That’s not informed consent. That’s negligence.

Chris Jahmil Ignacio

December 10, 2025 AT 07:14They don’t want you to know this because if you did you’d stop taking all the drugs. Big Pharma knows the gene link. They’ve known for 15 years. They could’ve made testing mandatory. They didn’t. Why? Because they make billions off people getting sick. And then they sell you more drugs to fix the damage. It’s not a syndrome - it’s a business model. Wake up.

Paul Corcoran

December 10, 2025 AT 22:41Thank you for posting this. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen this too many times. One patient came in with a rash and fever - we thought it was flu. Turned out she’d started carbamazepine 5 weeks prior. She almost died. Since then, I’ve started asking every patient: ‘What meds did you start in the last 6 weeks?’ It’s changed how I practice. You’re not alone. We’re learning.

Colin Mitchell

December 12, 2025 AT 20:10Hey - if you’re reading this and you’re on allopurinol or any of those meds? Don’t panic. Just be aware. Talk to your doc. Ask about HLA-B*58:01. It’s a simple blood test. If you’re from Africa, Asia, or Latin America? Even more reason to ask. Knowledge is power. You got this.

Stacy Natanielle

December 13, 2025 AT 21:19It’s interesting how the medical community continues to pathologize patient intuition. The data is clear. The biomarkers are validated. Yet, patients who report delayed-onset rashes are still dismissed as ‘anxious’ or ‘overly sensitive.’ This is not a failure of the patient - it’s a failure of systemic epistemic injustice in clinical practice. 🧠🩺

kelly mckeown

December 14, 2025 AT 03:36My mom had this. She’s okay now, but I still check in every week. I just wanted to say - you’re not crazy if you feel scared. It’s okay to ask for help. And if you’re reading this and you’re scared? You’re not alone. I’m here.

Tom Costello

December 14, 2025 AT 12:10Just wanted to add - in Canada, some provinces now cover HLA-B*58:01 testing for high-risk patients on allopurinol. It’s not perfect, but it’s progress. If you’re in the US and your doc says ‘it’s not standard,’ ask them to check the ACR guidelines. They changed them in 2020. Knowledge is power - and it’s also a right.