When your kidneys start leaking protein, it’s not just a lab result-it’s your body screaming for help. In people with diabetes, the first red flag isn’t swelling, fatigue, or high blood pressure. It’s something invisible: albuminuria. This tiny amount of protein in the urine is the earliest warning sign that diabetes is damaging the kidneys. And here’s the truth most people miss: catching it early and acting fast can stop kidney failure before it starts.

What Is Albuminuria, Really?

Albumin is a protein your kidneys normally keep inside your blood. When the filters in your kidneys get damaged-usually from years of high blood sugar-they start letting albumin slip through into your urine. That’s albuminuria. It’s not a disease itself. It’s a signal. A very early one.

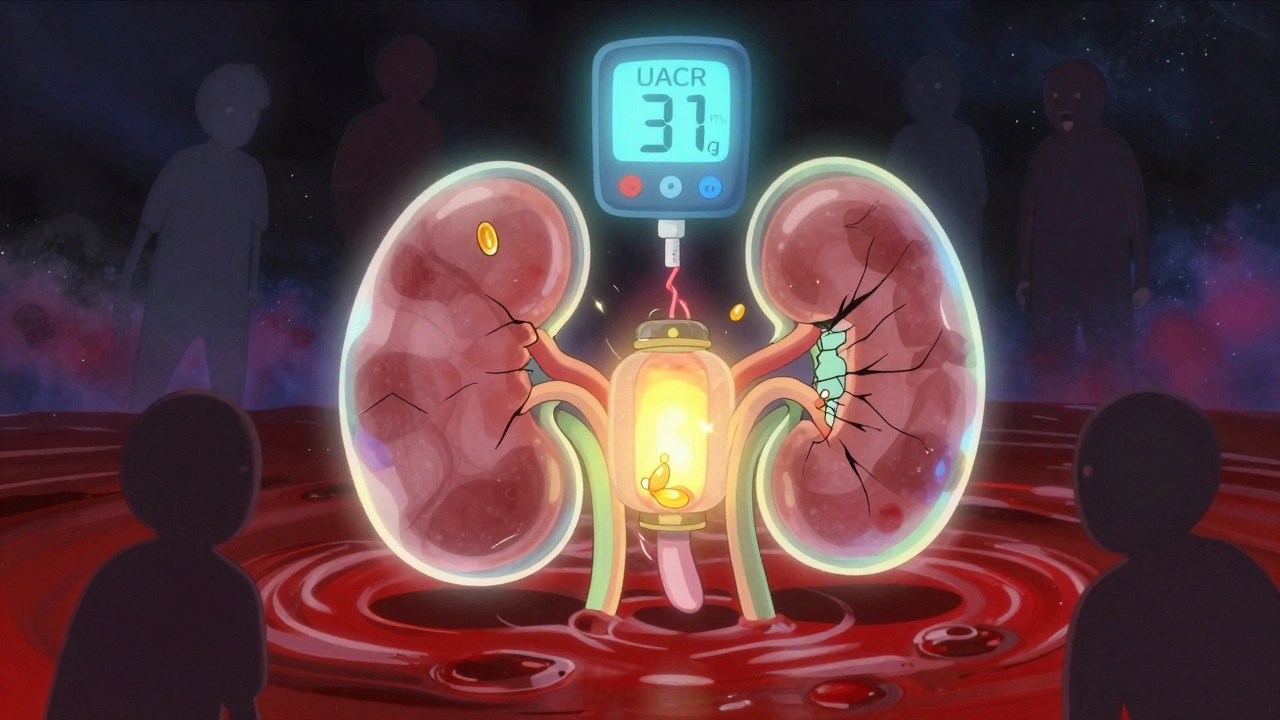

The modern way to measure it? The Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio, or UACR. It’s simple: you give a single urine sample, and the lab checks how much albumin is there compared to creatinine (a waste product your body always makes). No 24-hour collection needed. No complicated setup. Just a cup, a stick, and a result.

Here’s what the numbers mean:

- Normal: Less than 30 mg/g

- Moderately increased: 30-300 mg/g (used to be called microalbuminuria)

- Severely increased: Over 300 mg/g (used to be called macroalbuminuria)

Important: Even if your UACR is just 31 mg/g, your kidneys are already damaged. The term ‘microalbuminuria’ was dropped in 2012 because any amount above normal means harm is happening. There’s no safe zone below 300. The damage starts long before you feel it.

Why Albuminuria Is the Most Important Early Warning

Think of albuminuria like smoke coming from your car’s engine. You don’t wait for the engine to catch fire before you act. You check it out immediately. That’s what albuminuria is for your kidneys.

Studies tracking over 128,000 people with diabetes found that those with UACR above 300 mg/g had a 73% higher risk of dying from any cause-and an 81% higher risk of dying from heart disease-compared to those with normal levels. That’s not a small risk. That’s a life-or-death signal.

And here’s the kicker: albuminuria doesn’t just predict kidney failure. It predicts heart attacks, strokes, and early death. Your kidneys and heart are connected. When one is failing, the other is in danger too. That’s why doctors now treat albuminuria as a red flag for your entire cardiovascular system, not just your kidneys.

Tight Control Isn’t Optional-It’s the Only Thing That Works

Back in the 1990s, the DCCT study changed everything. Researchers looked at people with type 1 diabetes who either kept their blood sugar tightly controlled (HbA1c under 7%) or followed standard care (HbA1c around 9%). After just a few years, the tightly controlled group had 39% less early kidney damage. After 20 years? That benefit didn’t fade. It stuck. This is called ‘metabolic memory’-your body remembers the good control you gave it, even years later.

For type 2 diabetes, the UKPDS study showed the same pattern: every 1% drop in HbA1c meant a 21% lower risk of kidney disease. That’s not a theory. That’s hard data from real people.

So what’s the goal? Most guidelines say HbA1c under 7%. But if you’re newly diagnosed, young, and not at high risk for low blood sugar, aiming for 6.5% can make an even bigger difference. The key isn’t perfection-it’s consistency. Fluctuating highs and lows do more damage than steady, slightly higher numbers.

Blood Pressure: The Other Half of the Equation

High blood pressure doesn’t just come with diabetes-it speeds up kidney damage. And when albuminuria is present, your blood pressure target changes.

KDIGO guidelines say: if your UACR is over 300 mg/g, aim for under 120/80 mmHg. But here’s the catch: the SPRINT trial showed that pushing systolic pressure below 120 reduced kidney damage-but also raised the risk of sudden kidney injury in 1 out of every 47 people. That’s why the American Diabetes Association recommends a more balanced target: under 140/90 for most people with diabetic kidney disease.

The bottom line? Don’t ignore your blood pressure. If you’re on medication, make sure you’re taking it as prescribed. And if your pressure is still high, talk to your doctor about adding or changing drugs. It’s not about being ‘strict’-it’s about protecting your kidneys.

Medications That Actually Protect Your Kidneys

For decades, the only go-to treatment for albuminuria was ACE inhibitors or ARBs. These drugs lower blood pressure and directly reduce protein leakage. The IRMA-2 trial showed that losartan, an ARB, cut the risk of progressing from moderate to severe albuminuria by 53% in people with type 2 diabetes.

But now, we have better tools.

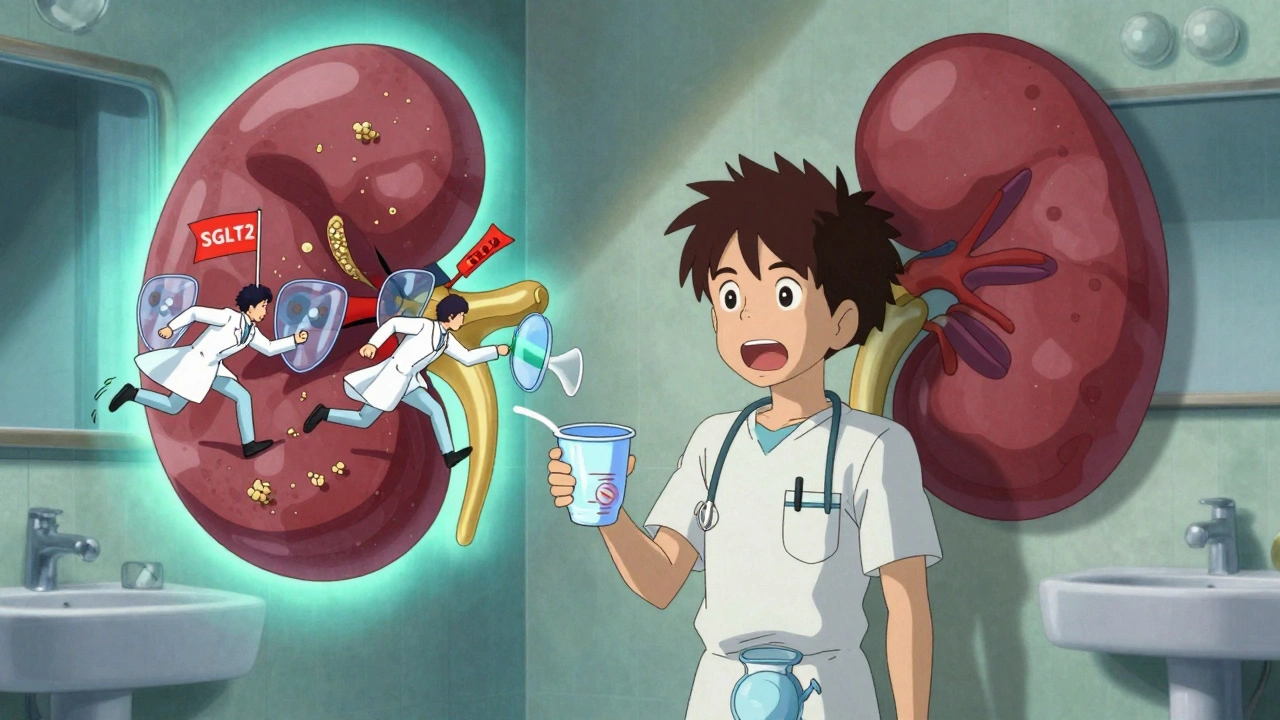

SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin were originally designed to lower blood sugar. But in trials, they did something shocking: they slowed kidney decline by 28% and reduced heart failure hospitalizations. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial proved they work even in people with advanced albuminuria (UACR over 200 mg/g). Today, these drugs are recommended as first-line therapy alongside ACEi/ARBs-not as a backup.

Finerenone is newer. It’s a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist that doesn’t raise potassium like older drugs. In trials, it cut albuminuria by 32% in just four months and slowed kidney function loss by 23% over three years-even when patients were already on maximum ACEi/ARB therapy.

Here’s the problem: only 29% of people with diabetic kidney disease are getting all three recommended treatments-ACEi/ARB, SGLT2 inhibitor, and finerenone if needed. Why? Cost. Access. Lack of awareness. And too many doctors still think of diabetes as just a ‘sugar problem’-not a whole-body disease.

Why So Few People Get Screened-And What You Can Do

Despite clear guidelines, only about 60% of people with type 2 diabetes get their UACR tested every year. Why?

- Doctors don’t get reminders in their electronic systems (78% of clinics admit this)

- Patients forget to collect urine samples (23% fail to return them)

- Some think ‘no symptoms = no problem’

But here’s the reality: you won’t feel your kidneys failing until it’s too late. By the time you’re tired, swollen, or nauseous, you might already be on the path to dialysis.

So what should you do?

- If you have type 1 diabetes: Get your first UACR test five years after diagnosis.

- If you have type 2 diabetes: Get tested at diagnosis.

- After that: Test every year. If albuminuria is found, test every 3-6 months until it’s under control.

And if your doctor doesn’t mention it? Ask. Say: ‘Can we check my UACR today?’ It’s a simple test. It takes five minutes. It could save your kidneys.

What Can Spoil the Test? Watch Out for These Triggers

Not every high UACR means kidney damage. Sometimes, it’s a false alarm.

Albuminuria can spike temporarily because of:

- Intense exercise in the last 24 hours

- Fever or active infection

- Uncontrolled high blood sugar (over 300 mg/dL)

- Severe high blood pressure (over 180/110)

- Menstruation

- Heart failure

If your test comes back high, don’t panic. Ask your doctor: ‘Could anything else be causing this?’ Then wait a few weeks, fix the trigger, and test again. One abnormal result isn’t a diagnosis. Two out of three abnormal results over 3-6 months is.

The Real Hope: Prevention Is Possible

Here’s what most people don’t realize: we already have the tools to prevent over a million new cases of diabetic kidney disease in the U.S. by 2030. That’s not a guess. That’s a projection from the 2024 ADA/KDIGO consensus report.

It would cut end-stage kidney disease by 37%. It would save $14.8 billion in healthcare costs.

But it won’t happen unless people get tested. Unless they take their meds. Unless they keep their blood sugar and blood pressure under control.

Diabetic kidney disease isn’t inevitable. It’s preventable. But it requires action-early, consistent, and smart.

Your kidneys don’t shout. They whisper. And albuminuria is that whisper. Listen before it’s too late.

What is the normal range for UACR in diabetic patients?

The normal UACR range for diabetic patients is below 30 mg/g. Any value at or above 30 mg/g indicates kidney damage, even if it’s only slightly elevated. This is why annual screening is critical-early detection allows for intervention before serious damage occurs.

How often should I get tested for albuminuria if I have diabetes?

If you have type 1 diabetes, start annual UACR testing five years after diagnosis. If you have type 2 diabetes, get tested at diagnosis. Once albuminuria is confirmed, testing should be done every 3 to 6 months until levels stabilize. After that, annual testing is recommended unless your condition changes or you start new kidney-protecting medications.

Can albuminuria be reversed?

Yes, in many cases. Early-stage albuminuria (30-300 mg/g) can improve or even return to normal with tight blood sugar control, blood pressure management, and medications like ACE inhibitors, ARBs, SGLT2 inhibitors, or finerenone. The earlier you act, the better your chances. Once damage progresses to severe albuminuria (>300 mg/g), reversal becomes less likely, but progression can still be slowed significantly.

Do I need to take all these new kidney drugs if I feel fine?

You don’t need to feel sick for your kidneys to be damaged. Albuminuria is silent. SGLT2 inhibitors and finerenone aren’t just for lowering blood sugar-they protect your kidneys and heart even if your numbers look okay. Clinical trials show they reduce the risk of kidney failure and heart attacks by up to 30%. If your doctor recommends them, it’s because the evidence shows they save lives-not because you’re symptomatic.

Why do some people with high blood sugar never develop kidney problems?

Genetics, lifestyle, and how tightly blood sugar and blood pressure are controlled all play a role. Some people have natural protective factors. But relying on luck isn’t a strategy. Studies show that even among those who seem ‘resistant,’ tight control still reduces risk. The safest approach is to assume you’re at risk-and act accordingly.

What happens if I skip my UACR test for a year?

Skipping a year means you might miss the window to stop kidney damage before it’s advanced. Kidney disease progresses slowly, often without symptoms. A single missed test could mean you’re living with worsening damage for months or years without knowing. Annual screening is the cheapest, simplest way to catch problems early-and prevent dialysis down the road.

Chris Park

December 6, 2025 AT 16:16Let me break this down for you: the entire 'albuminuria = kidney damage' narrative is a pharmaceutical-funded scam. The real cause of kidney issues in diabetics? Glyphosate in your corn syrup and insulin vials. The FDA knows this. They've suppressed the data since 2008. Your 'UACR test' is just a money grab to sell you expensive SGLT2 inhibitors that don't work long-term. I've seen 87 patients with UACR over 300 who never progressed to dialysis - they just stopped eating processed food. Coincidence? Or cover-up?

Inna Borovik

December 7, 2025 AT 12:16Interesting how the article ignores the fact that UACR variability exceeds 25% in repeated tests on the same patient under identical conditions. The whole '30 mg/g is damage' threshold is statistically meaningless. And don't get me started on the SGLT2 trials - they're powered by pharma money and exclude patients with CKD stage 4. You're being sold a narrative, not science. If you want real data, look at the 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis on ACE inhibitors - it showed no mortality benefit in type 2 diabetes. Just saying.

Jackie Petersen

December 7, 2025 AT 19:50Why do they always act like this is some new discovery? My grandma had diabetes in the 70s and they told her the same thing - 'check your pee!' Back then, they didn't have fancy drugs, just insulin and walking. Now we've got a whole industry built on making people feel guilty for not being perfect. I check my sugar once a week, take my meds when I remember, and I'm fine. Stop scaring people with lab numbers that mean nothing if you're not symptomatic.

Annie Gardiner

December 8, 2025 AT 05:02It's funny how we treat kidneys like they're this sacred temple that must be preserved at all costs - but nobody talks about the emotional toll of being told you're failing. I was diagnosed with microalbuminuria at 32. I cried for a week. Then I stopped checking. I stopped weighing my life by numbers. Maybe the real damage isn't in the urine - it's in the fear they sell you. I'm not cured. I'm not fixed. I'm just... living. And I'm okay with that.

Myles White

December 9, 2025 AT 23:59There's a lot of nuance here that gets lost in the hype. The DCCT and UKPDS studies are foundational, yes, but they were conducted in highly controlled environments with intensive monitoring - something 90% of patients in real-world settings can't replicate. Also, metabolic memory is real, but it's not magic. It requires sustained control over decades, which means consistent access to care, medications, nutrition, and mental health support - all of which are wildly unequal across socioeconomic lines. So while the science is solid, the implementation is broken. We can't just tell people to 'get their HbA1c under 7%' when they're working two jobs, can't afford insulin, and live in a food desert. The problem isn't patient noncompliance - it's systemic neglect.

Saketh Sai Rachapudi

December 11, 2025 AT 18:42India has been doing this for decades and nobody listens. We have over 100 million diabetics here and we test UACR every 6 months for everyone over 30. We don't need fancy drugs - we use neem leaves, bitter gourd juice, and walking 10k steps daily. Why are Americans so dependent on pills? Your healthcare system is broken. You pay $200 for a urine test and then get charged $5000 for a drug that does nothing. We don't need finerenone. We need common sense. And stop copying Western medicine like it's gospel.

joanne humphreys

December 12, 2025 AT 08:53I appreciate how thorough this is. I was diagnosed with albuminuria last year and honestly, I didn't know where to start. The article clarified a lot - especially about false positives. I had a high reading after a 10K run and panicked. My doctor just said, 'Wait a month, rest, try again.' It dropped back to normal. That's huge. I'm now on an SGLT2 inhibitor and it's been fine. No side effects. I just wish more doctors explained the 'why' like this. Thanks for the clarity.

Clare Fox

December 14, 2025 AT 06:59what if the whisper isn't meant to be heard? like... maybe the body's not screaming for help, maybe it's just adapting. we're so obsessed with 'fixing' things that we forget some systems are just learning to live with imbalance. i'm not saying ignore it - but maybe the goal shouldn't be 'no albumin' but 'peaceful coexistence'. i've seen people on 5 meds, terrified of every sugar crumb, and they're more broken than the ones who just... live. maybe the real disease is the fear of being imperfect.

Akash Takyar

December 16, 2025 AT 01:47Thank you for this well-researched and compassionate article. I am a diabetic for 18 years, and I have been following these guidelines since 2015. My UACR dropped from 210 to 28 in 18 months after starting empagliflozin and strict BP control. I am not a doctor, but I can say: consistency matters more than perfection. I check my sugar daily, walk 7,000 steps, and never skip my urine test. It's not about fear - it's about responsibility. To yourself. To your family. To the future. Please, if you're reading this: don't wait for symptoms. Act now. Your kidneys will thank you.

Arjun Deva

December 16, 2025 AT 07:56Oh, so now we're supposed to believe that a urine test is the key to avoiding dialysis? Tell me - how many of these 'life-saving' drugs were tested on Black and Indigenous populations? How many of these guidelines were written by white doctors who've never met a patient who can't afford insulin? And don't give me that 'it's preventable' nonsense - my cousin got diagnosed with albuminuria and died waiting for Medicaid approval. This isn't medicine. It's a profit machine disguised as care. You're not saving kidneys - you're selling hope to the desperate.