Drug Interaction Checker for Acid-Reducing Medications

Check Your Medication Interactions

This tool helps you understand how acid-reducing medications might affect the absorption of other drugs you take.

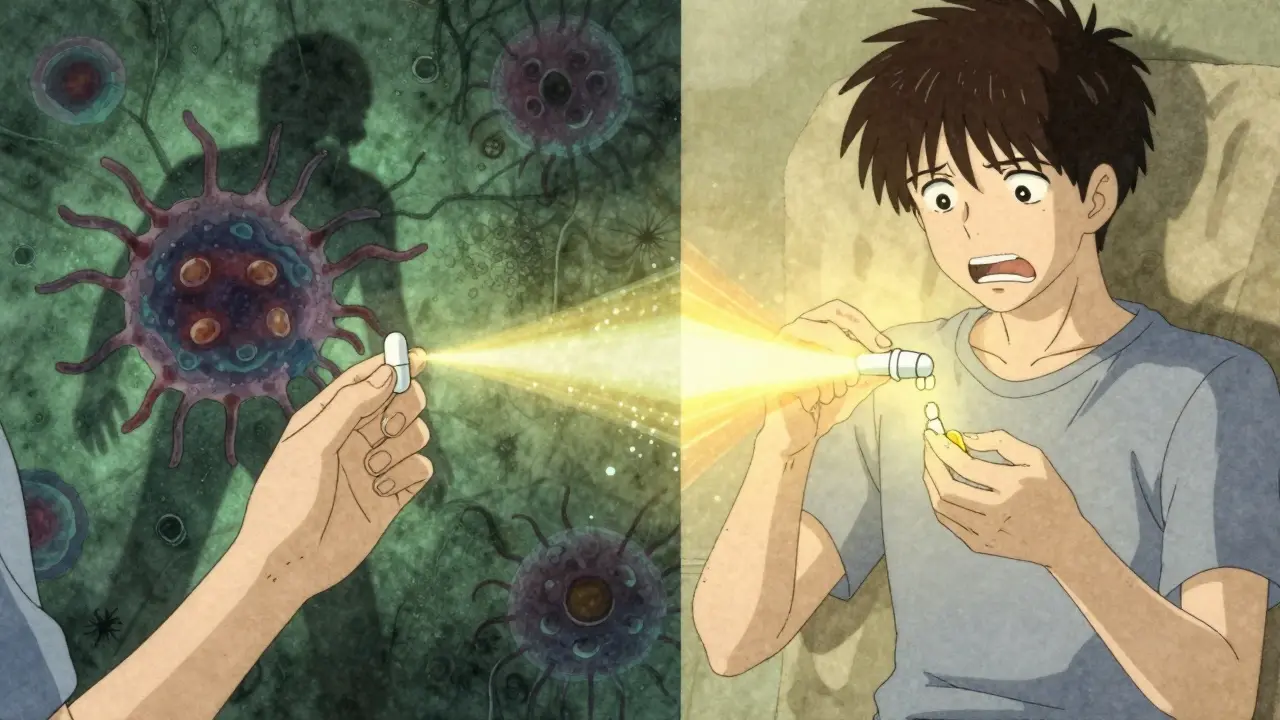

Most people take acid-reducing medications like omeprazole or famotidine for heartburn or stomach ulcers without thinking twice. But what they don’t realize is that these drugs can quietly sabotage the effectiveness of other medications they’re taking. It’s not a rare edge case - it’s happening to millions. In fact, acid-reducing medications interfere with the absorption of at least 15 commonly prescribed drugs, sometimes dropping their blood levels by 75% or more. This isn’t theoretical. People have lost control of their HIV, had leukemia treatments fail, and seen their blood pressure spike - all because no one told them that their heartburn pill could be ruining their other meds.

How Acid-Reducing Drugs Work - And Why It Matters

Acid-reducing medications fall into two main groups: proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole, esomeprazole, and lansoprazole; and H2 blockers like ranitidine and famotidine. Both lower stomach acid, but they do it differently. PPIs shut down the acid-producing pumps in your stomach lining for up to 24 hours. H2 blockers just block the signal that tells your stomach to make acid, and their effect lasts about half as long.

Normal stomach acid is strong - pH between 1 and 3.5. That’s close to battery acid. When you take a PPI, that pH can jump to 5 or 6. That might sound like a small change, but in the world of drug absorption, it’s a massive shift. Most oral drugs don’t dissolve well in acid. They need a certain pH to become soluble enough to get absorbed into your bloodstream. Weakly basic drugs - meaning drugs with a chemical structure that prefers a less acidic environment - are especially vulnerable. When the stomach gets too alkaline, these drugs don’t dissolve at all. They just sit there, undigested, and pass through your system without doing anything.

The Drugs Most at Risk

Not all drugs are affected equally. The real danger lies with drugs that are weak bases, poorly soluble, and have a narrow therapeutic window - meaning there’s a tiny difference between a helpful dose and a useless or dangerous one.

- Atazanavir (an HIV drug): When taken with a PPI, its absorption drops by up to 95%. People on this combo have seen their viral load skyrocket from undetectable to over 10,000 copies/mL. The FDA says: do not use together.

- Dasatinib (a leukemia drug): Absorption drops by 60%. Without enough in the blood, cancer cells grow unchecked. Studies show patients on PPIs have 37% higher treatment failure rates.

- Ketoconazole (an antifungal): Absorption drops 75%. It becomes practically useless. Many doctors now avoid prescribing it entirely because of this.

- Dasiglucagon (for low blood sugar): This one’s the exception. It’s a weak acid, so higher pH makes it absorb better - but only by 15-20%. Not enough to matter clinically.

These aren’t obscure drugs. Atazanavir is used in HIV treatment regimens worldwide. Dasatinib is standard for chronic myeloid leukemia. Ketoconazole, though less common now, is still used for stubborn fungal infections. If you’re taking any of these, and you’re also on a PPI, you’re at real risk.

Why the Small Intestine Doesn’t Save the Day

You might think: ‘But most drugs are absorbed in the small intestine, not the stomach. So why does stomach acid matter?’

Good question. The small intestine has a huge surface area - 200 to 300 square meters - and it’s where most drugs get absorbed. But here’s the catch: dissolution happens first. If a drug doesn’t dissolve in the stomach, it doesn’t get broken down into small enough particles to be absorbed later. Think of it like a pill that never melts. Even if it reaches the small intestine, it’s still a solid lump. The body can’t absorb it. The stomach is the starting line - if the drug doesn’t get off the blocks, it won’t finish the race.

Enteric-coated pills make this worse. These are designed to survive stomach acid and dissolve only in the intestine. But if the stomach pH rises too high, the coating can break down too early. The drug dissolves in the stomach - where it’s unstable - and gets destroyed before it even reaches the intestine.

PPIs vs. H2 Blockers: The Difference That Matters

Not all acid reducers are created equal. PPIs are far more dangerous when it comes to drug interactions. Why? Because they’re stronger and longer-lasting.

PPIs keep the stomach pH above 4 for 14 to 18 hours a day. That’s nearly the entire day. H2 blockers? They do it for 8 to 12 hours. That’s a big gap. A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open found PPIs reduce absorption of affected drugs by 40-80%, while H2 blockers only cause 20-40% drops. That’s not a small difference - it’s the difference between a drug working and failing.

Also, immediate-release pills are more vulnerable than extended-release ones. If you’re on a slow-release version of a weak base drug, you might get a little more leeway. But don’t assume it’s safe. Always check.

Real People, Real Consequences

This isn’t just a lab finding. It’s happening in living rooms, hospitals, and pharmacies across the country.

One Reddit user shared: ‘My viral load went from undetectable to 12,000 copies/mL after starting Prilosec for heartburn.’ Another wrote on Drugs.com: ‘My doctor didn’t tell me Nexium would interfere with my blood pressure meds - my readings were consistently 20 points higher until we figured it out.’

These aren’t anecdotes. The FDA’s adverse event database recorded over 1,200 reports of therapeutic failure linked to acid-reducing drugs between 2020 and 2023. Atazanavir led the list, followed by dasatinib and ketoconazole.

On the flip side, there’s hope. One study found that if you take dasatinib 12 hours before your PPI, 85% of patients regained full drug levels. Timing matters. Separating doses can help - but only if you know to do it.

What You Can Do

If you’re on an acid-reducing medication and take other prescriptions, here’s what you need to do:

- Check your meds. Look up every drug you take. If it’s a weak base with low solubility, it’s at risk. The big ones are atazanavir, dasatinib, ketoconazole, erlotinib, mycophenolate, and some iron and calcium supplements.

- Ask your pharmacist. Pharmacists are trained to catch these interactions. They see your full med list. Tell them you’re on a PPI or H2 blocker - don’t just say ‘I take something for heartburn.’

- Don’t stop your PPI without talking to your doctor. If you have a serious condition like a bleeding ulcer, you need it. But if you’re on it just because you ‘felt a little heartburn once,’ you might not need it at all. Studies show 30-50% of long-term PPI users have no valid reason to be on them.

- Consider timing. If you must take both, take the affected drug at least 2 hours before the acid reducer. For some drugs, 12 hours apart works better.

- Ask about alternatives. Antacids like Tums or Maalox work quickly and don’t last long. If you only need relief occasionally, they’re safer than daily PPIs. But don’t use them long-term - they can cause other problems.

The Bigger Picture

More than 15 million Americans take PPIs daily. About 15% of adults in developed countries use acid-reducing drugs long-term - often without proper monitoring. The FDA says 25-50% of the top 200 prescribed drugs are at risk. That’s a lot of people on drugs that might not be working.

The cost? Around $1.2 billion a year in wasted healthcare spending because drugs fail, patients get sicker, and need more tests, hospital visits, and stronger treatments.

Pharmacies are starting to catch on. Electronic health systems now flag dangerous combinations. One study showed pharmacist-led reviews cut inappropriate PPI use by 62%. But that’s not everywhere. You can’t rely on the system to protect you.

Drug companies are responding too. Nearly 40% of new medications in development now include special formulations to avoid pH-dependent absorption issues. That’s progress. But for now, you’re still on your own.

Final Thought

Acid-reducing medications aren’t harmless. They’re powerful tools - but like any powerful tool, they need respect. Taking them without knowing how they interact with your other meds is like driving with your eyes closed. You might get lucky. But the odds aren’t in your favor.

If you’re on one of these drugs - especially if you’re also on a prescription for HIV, cancer, or a serious infection - don’t assume everything’s fine. Ask. Double-check. Speak up. Your life might depend on it.

Can acid-reducing medications make my other drugs useless?

Yes. For certain drugs - especially weak bases like atazanavir, dasatinib, and ketoconazole - acid-reducing medications can reduce absorption by 60-95%. This can lead to treatment failure, disease progression, or dangerous side effects. These aren’t rare cases. They’re well-documented and often preventable.

Are H2 blockers safer than PPIs for drug interactions?

Generally, yes. H2 blockers like famotidine raise stomach pH less and for a shorter time than PPIs. Studies show PPIs cause 40-80% reductions in drug absorption, while H2 blockers cause 20-40%. But that doesn’t mean H2 blockers are safe. If you’re taking a high-risk drug like dasatinib, even a 30% drop can be dangerous.

What should I do if I’m on both a PPI and a high-risk drug?

Don’t stop either without talking to your doctor. For drugs like atazanavir, combining them with PPIs is strictly contraindicated - you need an alternative. For others, like dasatinib, spacing doses 12 hours apart can restore effectiveness. Your pharmacist can help you find a safe schedule or suggest a different acid reducer.

Can antacids like Tums be used instead of PPIs?

Antacids can be a safer short-term option. They work quickly and don’t last long, so they’re less likely to interfere with drug absorption. But they’re not for daily use - they can cause diarrhea, constipation, or electrolyte imbalances. If you need long-term acid control, talk to your doctor about alternatives like lifestyle changes or switching to a different medication.

Why don’t doctors always warn patients about this?

Many doctors don’t realize how common and serious these interactions are. Patients often take PPIs over the counter, and doctors may not know they’re using them. Also, drug labels don’t always make the risk clear. The FDA has updated warnings for 28 drugs since 2020, but awareness still lags behind the evidence. It’s up to you to ask: ‘Could this interact with my other meds?’

Lauren Wall

January 22, 2026 AT 18:13My pharmacist flagged this exact issue when I started omeprazole. I was on clopidogrel and didn’t even know they could interfere. Now I take my heartburn pill at night and my blood thinner in the morning. Simple fix. Why isn’t this common knowledge?

Liberty C

January 23, 2026 AT 12:47Let me be brutally honest: if you’re popping PPIs like candy because you had tacos last night, you’re not just wasting money-you’re risking your life. These drugs aren’t dietary supplements. They’re pharmacological sledgehammers. And the fact that people treat them like Tums is why healthcare costs are exploding. Wake up.

Lana Kabulova

January 24, 2026 AT 13:55Wait-so if you’re on dasatinib, and you take a PPI, your drug levels drop by 60%? That’s not just ‘might not work’-that’s ‘your cancer is growing while you think you’re being treated’?! And no one’s screaming about this?! The FDA has 1,200 reports-and still, pharmacies don’t auto-flag?!! This is systemic negligence!!

Rob Sims

January 26, 2026 AT 02:48Oh wow, another ‘pharma conspiracy’ post. Next you’ll tell me that water is dangerous if you drink too much. Everyone knows PPIs interact with stuff. That’s why you get the damn warning label. If you’re taking 5 drugs and didn’t read the insert, maybe stop blaming the system and start reading.

arun mehta

January 26, 2026 AT 18:16Respected colleagues, this is a matter of profound public health significance. In India, where polypharmacy is rampant and access to pharmacists is limited, such interactions are tragically under-recognized. I urge all readers: consult a registered pharmacist before combining any acid reducer with prescription medications. A simple 5-minute conversation can save lives. 🙏

Chiraghuddin Qureshi

January 28, 2026 AT 13:10Bro, I just saw this and thought of my uncle in Delhi-he’s on PPI for 5 years, and his diabetes meds stopped working. Doctor said ‘maybe it’s the sugar’-but what if it was the omeprazole? We need more awareness here too. 🙏💊

Patrick Roth

January 30, 2026 AT 11:30Actually, the real issue is that people are too lazy to eat better. If you’re taking PPIs daily, you’re probably eating fast food, soda, and stress-eating. Fix your diet. Stop blaming the drugs. And for the love of god, stop reading Reddit for medical advice.

Kenji Gaerlan

January 31, 2026 AT 00:30so like… ppi’s mess with other meds? ok but like… i’ve been on nexium for years and my blood pressure is fine so idk… maybe it’s just a myth? or maybe i’m just lucky??

Oren Prettyman

January 31, 2026 AT 07:54It is imperative to recognize that the phenomenon described herein is not merely a pharmacokinetic curiosity, but a systemic failure in clinical communication, patient education, and regulatory enforcement. The confluence of overprescription, patient non-disclosure, and insufficient pharmacovigilance constitutes a public health crisis of epistemological proportions. One must question the very epistemic foundations of modern pharmacotherapy when a drug with a 95% reduction in bioavailability is still marketed as ‘safe’ for concurrent use without explicit, mandatory patient counseling protocols.

Tatiana Bandurina

February 1, 2026 AT 16:11I’m just saying… if your doctor didn’t warn you, maybe they’re not as competent as you think. And if your pharmacist didn’t catch it, maybe you’re not getting the care you deserve. You’re not paranoid. You’re just paying attention.

Philip House

February 1, 2026 AT 16:16Yeah, and what about the fact that most of these drugs were developed by Big Pharma to make you dependent? They don’t want you to fix your diet-they want you to buy pills forever. PPIs? They’re a cash cow. The ‘interaction’ thing? Just a distraction so you don’t ask why you’re on 12 meds in the first place.

Akriti Jain

February 2, 2026 AT 16:15So… this is all a lie, right? The government and pharma are using this ‘drug interaction’ thing to scare you into buying more expensive meds. They want you to think PPIs are dangerous so you’ll switch to $300/month ‘alternative’ treatments. The real danger? They’re watching you read this. 🤫👁️

Mike P

February 3, 2026 AT 14:18Bro, I took omeprazole for 3 years and my HIV meds were fine. My viral load stayed undetectable. So yeah, maybe it’s true for some people-but I’m living proof it ain’t always a death sentence. Don’t scare people with ‘95% drop’ stats if you don’t know their exact regimen. Not everyone’s the same.

Jasmine Bryant

February 3, 2026 AT 17:43Just a heads up-mycophenolate and iron supplements are also affected. I didn’t realize my anemia got worse after starting pantoprazole until my doctor checked. Took me 6 months to connect the dots. Always ask about interactions, even if it seems ‘minor.’

shivani acharya

February 4, 2026 AT 14:51Okay, so let me get this straight-pharma companies knew this for decades, but they buried it because PPIs are the most profitable drugs on the market? And now they’re pretending to ‘fix’ it with ‘timing advice’? That’s not a solution-that’s damage control. And don’t even get me started on how they pushed these drugs as ‘safe for long-term use’ while knowing the risks. We’re all lab rats. 😈